The Wildcraft Drones

By Thea Kinyon Boodhoo

Note from the Author: Forests are the most productive ecosystems on land. They create their own fertilizer, keep streams healthy, draw rain inland instead of using up reservoirs, handle pests by providing habitat for predators, and move carbon from air to earth, instead of the other way around. Is it possible, then, for forests to be our farms?

“I’d like an apple.”

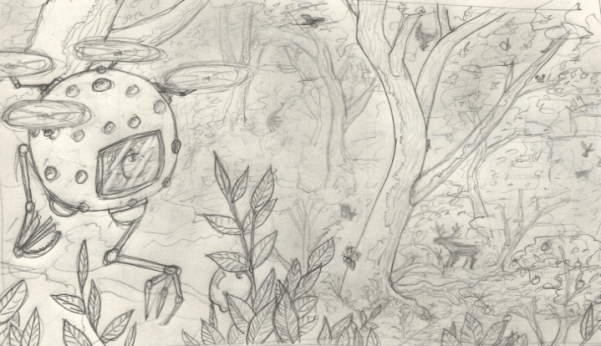

A small flying machine beeps acknowledgment and whizzes into the dense wildcraft forest that fills the horizon from my 42nd –story balcony, a green backdrop to a towering city of 100 million humans.

It was drones like mine that made the forest possible. For thousands of years humankind grew food in rows, because rows were usable for humans and their plows and ox, their tractors and their irrigation systems. Yet the most productive land on Earth was impenetrable rainforest. Not until small, intelligent, flying robots became common did humanity find it practical to use the system that trees found by accident.

Every edible, medicinal or otherwise useful plant and fungus that thrives in this climate is found outside the city, tangled in rich forest, sharing land that no human would find comfortable with wildlife and weeds. More species are packed into the wildcraft that surrounds my city than were grown in every pre-drone human farm combined.

The drones, like rockets, like yo-yos, were first built for war. Metal birds with software to recognize the face of a terrorist while skimming the clouds. Directed by governments, they killed more children than they did terrorists, but the technology spread to industries and citizens and became cheap. Now the descendents of killing machines zip through the canopy of fruit trees on the whims of a new generation.

A hum. My drone is back. It slows and rests on my balcony ledge, displaying a photo of an apple on its softly glowing flatscreen face. Tap and its belly opens, a compartment that expands and contracts to fit what it finds, like the crop of a bird.

The apple is the same one from the photo. My flying friend is a computer with a camera (and much more) and it knows its forest leaf by leaf, in four dimensions. It knew this apple was ripe because it watched it bloom as a flower, saw it pollinated by a bee whose name it knew, calculated its maximum fructose content and circumference based on the weather over the course of the season. My drone knows the rhythms of the twirling vines as they search the air for branches to climb, and it knows the subtle differences in growth patterns between its own range here and one three degrees north, because it shares its consciousness with every other wildcraft drone, everywhere in the world. Together they give us a real-time, high-accuracy model of all wildcraft, helping us maintain and optimize it. The knowledge we’ve gained just from what they see as they collect our food, meal by meal, has taught us more about how forest ecosystems work over the past four decades than in all of prior human history combined, times hundreds, and we learn more every day. We’ve used this constant learning to optimize the wildcraft for almost every viable location on land. We’ve used it to start re-greening the Sahara, sowing food-bearing flora into the desert from the edges in, using the breath of a biodiverse forest to spread life, wealth and rain across a continent.

The tropical African wildcraft looks nothing like mine of course – the species are native from nearby, or de-extinctioned from the genetic material of well-preserved fossil pollen from the plants that lived there before it was desert.

I could see the Sahara wildcraft through the eyes of its own drones in virtual reality right now if I wanted. I could explore an almost-complete, three-dimensional, videorealistic recreation of it based on data gathered by the sensory organs of the drones – cameras, microphones, lidar, even ultraviolet and infrared, translated for my cone-and-rod eyes into glowing shades that could tell me the health of the plants at a glance if I knew how to interpret it.

The environmentalists of my generation despair at the loss of savannahs and scrubland. The older ones remember a stark high prairie outside my city, Albuquerque, where our famous sunsets once lit sagebrush-speckled rock and dust. I learned about it when I was a kid, asking why the Sandia mountains were named after watermelon. They showed me pictures of yellow grass and stone mountainsides bathed in pink sunsets. It was beautiful. Different.

Biodiversity means productivity, but maybe there was something to be said for an unproductive ecosystem, a barely-getting-by, on-the-verge-of-drying-up landscape that didn’t serve human needs at all. Who are we to say the rocks don’t need glaring sun on them, and dry lichen, and horny toads? The “Great American Desert” is still there, in patches in Nevada, but most of the West is wildcraft now. Many lament its loss, even while they snack on the fruits of what replaced it. I’m glad we’ve solved so many problems of agriculture and sustainability, but I hope they save a piece of desert forever. I like the idea of it still existing somewhere.

The countryside fences are gone. The roadkill-smeared freeways are gone. The endless herds of cows are gone, and wolves, deer, bear and big cats are more plentiful than they’ve ever been in North America, roaming dense, unbroken forest floor from coast to coast. From space our planet is dotted with bright connected nodes at night, in a sea of black – the old glow of suburb-filled continents has condensed and dimmed into an efficient web of cities. In time-lapse the Earth at night over the past two centuries would look like some glowing liquid had spilled over the whole planet, then cooled and cured into a concentrated, highly-functional network. We look like a civilization from space now, instead of a slime mould.

The vast majority of humanity lives in dense, clean cities. We use our drones to explore the wildcraft virtually, if we’re curious. Those who study and engineer the wildcraft are well trained and equipped for the dangers of true wilderness when their work takes them into the thick of it. I think every kid goes through a phase where they want to be a wildcrafter when they grow up. I still dream about it.

I take the last slightly-bitter bite of my apple and give the core to my drone. The core is returned to the forest, where it will be a feast for something else.

Thea Kinyon Boodhoo is a writer, designer and naturalist who happily pays membership dues to the Long Now Foundation, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, and Geological Society of America. Her primary interest is the exploration of worlds hidden in deep time, along with their myriad creatures and complexities. She sees ecology as a useful window to the past – and occasionally, when the light hits it just right, a spyglass to the future.

Thea Kinyon Boodhoo is a writer, designer and naturalist who happily pays membership dues to the Long Now Foundation, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, and Geological Society of America. Her primary interest is the exploration of worlds hidden in deep time, along with their myriad creatures and complexities. She sees ecology as a useful window to the past – and occasionally, when the light hits it just right, a spyglass to the future.

Further Reading

-

USDA National Agroforestry Center: https://nac.unl.edu/index.htm

-

The World Agroforestry Center: https://www.worldagroforestry.org/

-

“A Quiet Push to Grow Crops Under Cover of Trees,” New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/22/science/quiet-push-for-agroforestry-in-us.html

-

“Wildcrafting Non-timber Forest Products — Environmental Issues,” University of Kentucky Center for Crop Diversification, https://www.uky.edu/Ag/CCD/introsheets/wildcraftenviron.pdf

-

On de-extinciton:

https://longnow.org/revive/category/de-extinction/

https://www.ted.com/talks/stewart_brand_the_dawn_of_de_extinction_are_you_ready?language=en

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/deextinction/

https://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2013/04/125-species-revival/zimmer-text