Family and Nature

Perhaps a year ago, Coreopsis invited me to engage in an interview process. With an invitation, “Please tell us a bit about yourself,” I received these questions:

What are your primary influences as an artist?

What are you working on now?

When you look over your body of work, what do you think is your overall “grand vision” or “burning questions”?

What have you found most challenging in creating art and balancing a career, family, and other commitments?

What would you like to share about your individual or collaborative writing/art projects?

What’s next to you?

I disliked these questions; each one felt like a box, limiting what I could share, determining the direction of answers. Too much like the typical American question, “What do you do?” I asked myself, “If not that, then what?” If I didn’t answer these questions, how did I want to engage in this interview process?

Reminded that I don’t like the hierarchical structure of lectures where the audience asks questions of the expert presenter, that the audience holds their own expertise and lived experience, and that I prefer a back-and-forth conversation where both are vulnerably revealing self, in process, held in the container of relationship.

For this interview, I discovered that I preferred a conversation, a genuine engagement, back and forth. I wanted to know the following: why did you select me for an interview? What intrigues you? What do you want to learn? How will this information be useful to you, integrated into your life and work? So, I invite the Coreopsis editor, Lezlie Kinyon, to enter into this conversation, perhaps write a “Forward” or “Introduction”. Please.

I also recognize that there is a deadline for publication and that I made a commitment. So, I will move forward with the interview process as it is currently structured, while also inviting more conversation and engagement from Lezlie and from the readers. My purpose in answering these questions is to give a gift to the reader. Perhaps some aspect of this story will inspire you, support you in actualizing your talents and bringing your vision to fruition.

In my attempt to answer the questions thoroughly, I wrote hundreds of pages of history, thoughts, and stories. An unwieldy mass for this online journal format. I remind myself that every creative project has limitations and that these limits become part of the creative process. So, instead of sharing long stories, I’ll try to limit myself to underlying themes. Many people have asked me to write a book about my life. The pages I wrote can contribute to the book someday.

CJMT

Please tell us a bit about yourself

DB

I don’t accept what I’m given or told as absolute. I am engaged in an ongoing internal dialogue. I look for gaps and traps, I search for alternate paths, and I’m willing and capable of constructing what does not yet exist. The doctoral studies sharpened my mind like a steel-trap and the research process taught me how to take all this, to identify what’s missing, what is not yet explored or known, and how to construct research questions. I use this process in my artistic creativity, too.

In the mid 1400s in Bohemia, my ancestors were Hussites, one of the earliest reformist and anti-authoritarian movements in Europe. They did not accept the dogma or hierarchy or rigid beliefs of Catholicism. The Hussites published the Bible in the Czech language instead of Latin. They taught everyone–- even peasants and women–- to read so that individuals could read and interpret the Bible for themselves and they believed that individuals could experience God directly without mediation through priests and popes. Women gave sermons and women fought in the war. Declared heretics, the Holy Roman Empire, and the papacy attacked the Hussites during years of religious crusades. These themes of independence, education, direct relationship with the sacred, empowered women–- all this is evident in my life and work as an educator, mental health counselor, researcher, shaman, and artist.

CJMT

What are your primary influences as an artist?

DB

Family and nature.

My maternal ancestors travelled in steerage to the new world, homesteading and farming in Kansas. In my maternal grandmother’s family, siblings worked and pooled their resources so that all of them obtained college educations. My great aunts milked cows and used those wages to put their brother through an engineering degree. He then worked as an engineer in a city and paid for the college tuition of his sisters. That responsibility fulfilled, he turned his back on modernity, returned to the homestead, farmed with mules and horses, never bought a tractor, cooked on a wood stove, lived without indoor plumbing, and grew a long beard. Inspirational themes for me? Taking risks, travelling into the unknown, the value of education, and choosing to live off the beaten path.

My grandmother was assertive, intelligent, outspoken, an educator, powerful, the family matriarch. She studied to be a teacher in Kansas, then horticulture at the University of Colorado when it was a hotbed of feminism in the 1920s. Unusual for the time, she did not marry until in her 30s. She married a man seven years younger than her, also an immigrant. When he was seven years old, his education ceased when he left Bohemia with his father and brothers. They all worked in a meat packing plant, six days a week, in New York City. He was seven years old, working 48 hours a week. They saved their earnings to pay for their mother and sister’s passage, then took the train and a Conestoga wagon to Kansas. My grandmother taught her husband how to read English and subscribed to farm journals to educate him in his career. He built a room into their farmhouse, a library, for her wall of books and jazz records. She once mentioned that she would have liked to become a medical doctor, but that wasn’t accessible to her at that time. She did love science and educated me about plants, talked about trees.

My mother had the freedom to be a barefoot, jean-wearing tomboy who assisted her father with construction, mechanics, driving a tractor and using a shotgun to hunt rabbit, quail, and pheasant for the family’s dinner, before sewing clothes that she designed while listening to opera on the radio. As a child, I lived with the textures and patterns and colors of fabrics spread across the floor, as she pinned and cut patterns. Trips to fabric stores, wandering amidst the acrid smell of dyes and looking at the bolts of fabric organized by pattern, color, material. So visually rich. The high quality of my mother’s sewing, where plaid patterns would meet and match at seams with tiny, straight stitches and individualized tailoring. Although my family had little income, our home was beautiful thanks to the skills of my parents. Perhaps we ate waffles for supper, but there was money for my dance lessons, money for a flute.

I spent hours observing my dad as he did graphic design or as he worked on oil paintings. He was very exacting, a perfectionist. He thought it was odd that a child would sit so quietly, unmoving. I was mesmerized, and I was learning through observation. With the stressors of supporting a family of six, maintaining and forever remodeling our home, and working in our large garden, he eventually gave up painting. He never had a solo show, which I suspect was due to his difficulty communicating. His English was difficult to understand. He relied mostly on lip reading. One day, with a serious demeanor, he asked me to follow him. While I waited, he climbed into the attic and brought down boxes of his paints and brushes–- and silently gave them to me.

My parents often commented on design and many of our family dinnertime conversations were about beauty, a beautiful object, and, even more so, a beautiful scene. However, at breakfast, we shared our dreamworld. Without knowing about dream journals, each child kept a secret dream journal for years. My vivid dreams inspired an earlier style that came to fruition when I taught in the Native villages in the Alaskan bush, making 6’ and 8’ tall watercolor and gouache paintings, and charcoal and graphite drawings that were an intuitive combination of symbolic images.

My mother was claircognizant. She once stood up, picked up her purse, and informed her employer that she had to go home. When she unlocked our front door, dark smoke came roiling out. She ran inside and found the furnace malfunctioning, the walls around it red hot and smoldering. She saved our home from burning down. Another time, she asked me to go for a walk with her. This had never happened before. She led this way, then that way, down this street, up an alley, until we came to a backyard with the grass burning. Using a flat trash can lid, she suffocated the fire. In conversations with my adult siblings, it was revealed that we all had precognizant dreams. Now these “knowings” come when I am awake. I have knowledge of the future or knowledge of someone’s past, or I know people are having an affair. I was one of the artists studied in a research project, Art and Psi (Cardeña, Iribas-Rudin, & Reijman, 2012).

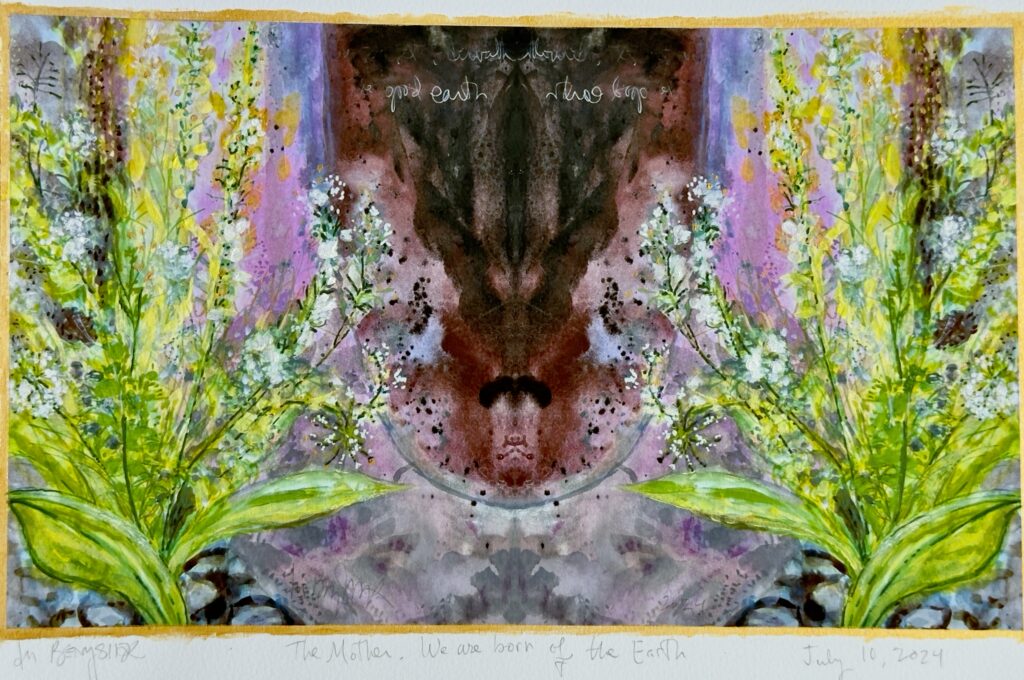

During my childhood, I had the run of my grandparents’ farm, the fields and pastures, orchard and vegetable garden, digging into the good, dark earth. My extended family often went camping, another immersion in nature. We always owned numerous pets, dogs, cats, chickens, ducks, rabbits. A mini farm in the fast food, aircraft-assembly wasteland of south Wichita. I have a keen, intimate relationship with animals, wild or domestic.

What are the essential themes here? A connection to Czech culture with remnants of Slavic animism, scraps of folk art in minor keyed songs, dances, quilts, and embroidery. A deep, ecstatic relationship with inspirited nature, a preference for being outdoors, in nature. The world of seeing, aesthetic sensibility, a highly developed sense of design. Direct experience of God. An anti-authoritarian stance that values freedom, independence, and education. Learning about science within the embrace of nature. Powerful women that lived outside strict gender norms. The creative ability to work with many materials, a love of work done by hand, and a dedication to high-quality work. A willingness to take great risks to travel, from the known into the unknown. And, also, to reject aspects of society and culture that are not a fit, to hold true to one’s heartfelt values.

The direct experience of the sacred and ecstatic experience of inspirited, animistic nature led to my initiation as a shaman, through a traditional Naerim Gut performed by three women shamans from South Korea. Before initiation, I could feel the energy fields around trees. After initiation, I could “see” the sparkling and colorful life energy emanating from plants, from leaves and flowers and seeds. I asked myself, “How can I represent the numinous in nature, the participation in the cosmic life cycle? How can I share what I experience in nature?” I asked myself these artist research questions over and over. Eventually, the answer emerged and, in January 2024, I began the Inspirited Nature series.

My son.

An artist friend keeps telling me to add a human figure to the painting, On the Day You Were Born. No. There are two people present here: the mother giving birth through mind-blowing waves of contractions and the child being born, the child’s head crowning through the cervix, both participating in that grand and infinite cosmic life cycle.

I must credit my son with the enormous influence and inspiration he’s had on me, as an artist, as a woman, and as a scholar. At age 42, I gave birth to him. Such an awesome experience, to be a powerful animal, giving life to my little baby. My son Hans, is kind, caring, wise, intelligent, thoughtful, and creative. His life gave me purpose and structure, devotion and commitment, and the groundedness required to provide him with a home.

We embrace in a melting hug, links in the great chain of being.

This is a good place to pause for now. In the future, I will continue answering these interview questions, sharing stories, gradually giving more insights and gifts to the reader.

References

Cardeña, E., Iribas-Rudin, A., & Reijman, S. (2012). Art and psi. Journal of Parapsychology, 76(1), 3-23.