Laetitia Barbier’s name has become familiar to many Tarot fans and scholars through her Instagram account, her Tarot readings and courses, and her work as the program director and head librarian of the New York-based Morbid Anatomy, a library and museum (founded 2007 by Joanna Ebenstein) that supports an ongoing program of virtual lectures and panel discussions. Barbier has put her Tarot practice and the skills she undoubtedly acquired while studying art history at the Sorbonne to good use in Tarot and Divination Cards: A Visual Archive, and Abrams made an excellent choice when they added her project to their new Cernunnos imprint.

Abrams has been paying attention to the ever-rising popularity of Tarot and the growing number of publishers who are finding it worth (a potentially lucrative) second glance. According to their website listings, Abrams first picked up The Antique Anatomy Tarot (2019) and The Arcana of Astrology Boxed Set: Oracle Deck and Guidebook for Cosmic Insight (2020) by Toronto artist Claire Goodchild for their “Abrams Noterie” gift and stationary imprint. The forthcoming Cats Rule the Earth Tarot by Catherine Davidson and illustrator Thiago Corrêa will be published under the Image imprint, which is dedicated to trends and obsessions in pop culture (2022). Barbier’s Tarot and Divination Cards, however, appears along with Cthulhu Dark Arts Tarot from the World of H.P. Lovecroft (2021) by Bragelonne Games and Barbier’s earlier Jesus Now: Art + Popular Culture (2021) as a Cernunnos title. The Cernunnos imprint is described as “a new publishing house showcasing books that inspire and intrigue” and that “highlights the creative spirit and passion in contemporary art and icons from painters, photographers, fashion influencers, filmmakers, and writers […]” While this information may all seem a bit beside the point of the book itself, it is vitally important to authors and artists who would rather not travel the path of self-publication. More publishers who are interested in Tarot means more options and more opportunities for these individuals. Sadly, not all publishers set their standards particularly high when it comes to Tarot—perhaps because they are under the mistaken notion that there are no standards in that field. Whether it is thanks to Abrams’s screening process or Barbier’s due diligence Tarot and Divination Cards is a credit to them both and will undoubtedly be a valued resource in the field for many years to come.

Rachel Pollack, author of The New Tarot: Modern Variations of Ancient Images (1990) and numerous other Tarot-related books, wrote a brief foreword for Tarot and Divination Cards titled “In the Beginning was the Voice.” Pollack clearly thinks Abrams did students of Tarot a service by publishing it and she, in turn, did Barbier a service by finding just the right way to inform readers that Barbier wrote the manuscript in English, which is her second language. Still, one would think that a publisher the size of Abrams could have provided a copy editor to smooth out the occasional oddity in grammar and diction just a little, because “just a little” is really all that was needed, and because many people don’t read forewords and may thus mistake the extraordinary for sloppiness. Shall we abandon these souls to the gravity of shinier baubles born of careful copy-editing and shallow research?

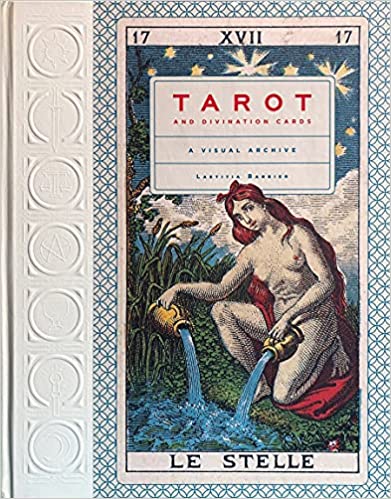

Tarot and Divination Cards has an understated embossed cover and page after page of between one and six thoughtfully chosen color reproductions of each card as well as paintings accompanied by accurate history, and intelligent commentary with notes. The book opens with Pollack’s preface, an introduction, and a short history, long sections on the major and minor “arcanas,” another hundred pages on cartomancy and divination games, and ends with a short section on modern Tarot, notes, selected bibliography, and acknowledgements. All of the Tarot and art books released in 2020-2021—is it four or is it five titles?—have something unique to offer, but this one takes the prize for accuracy, clarity of expression, and the sheer quantity of art work of interest to Tarot scholars. Beyond the reproductions of the cards themselves, Barbier’s pairings of non-Tarot art with Tarot will hold both general readers and academics enthralled: a painting of an emperor is matched with Emperor cards, a painting of a pope with the Hierophant card, a painting of Samson fighting the lion with the Strength card, an exceedingly gruesome fresco of a hanged man with the Hanged Man card, and the list goes on to include comparisons and supplementary images that do more than a thousand words to contextualize Tarot imagery. Ever wonder if you were the only person to see a certain affinity between the 3 of Swords in the late-fifteenth century Sola Busca deck and David’s “Oath of the Horatii” (1784)? Wonder no more: Barbier noticed it and not only lays the visual comparison out for everyone, she also offers an excellent historical description of the painting as substance for interpreting the card (226). She is very careful, however, to distinguish such affinities from direct historical connections. Anyone wanting to know more about any of these images will find that the labels meticulously identify artists, locations, dates, and so forth.

The images, from multiple historical Tarot and related decks, are invaluable for researchers. The section on the Fool alone, for example, includes reproductions of a detail from a 16th-century painting called “Laughing Fool,” and relevant cards from the Sola Busca Tarot (15th century), the Tarocchi Fine dalla Torre (Bologna, Italy, 17th century), the so-called Gringonneur or Charles VI Tarot (Northern Italy, 15th century), the Vieville Tarot (France 17th century), the Noblet Tarot (France, 1659), the Minchiate de Poilly (c. 1712 and 1741), Paris through the Centuries (1881), the Visconti-Sforza Tarot (Milan, 15th century), the so-called Mantegna Tarot (1540–1550), Tarot des Imagiers du Moyen Age by Oswald Wirth (1889) and, finally, Grand jeu de l’Oracle des Dames by G. Regamey, France (1890-1900). Some of these same decks and sources are represented in the other trump sections, and additional examples are included where they have something unique to add to the visual repertoire of a particular card. Most of the decks listed above will already be familiar to Tarot historians and collectors who own some or all the available facsimile editions, but the card arrangements offered here are still likely to be useful to them. They will be essential to students in search of a good grounding in the visual history of Tarot while saving their shopping dollars for more contemporary decks.

The section on cartomancy is an unexpected bonus, including an astonishing array of historical playing cards, a section on Etteilla, another on Madame Lenormand, still others on Madame Dulora de la Haye, La Sibylle des Salons, Das Aute Gottes: The Eye of God, and more, all copiously illustrated. Sadly, the chapter on modern Tarot is dedicated to numerous reproductions from a few decks, rather than many decks. At a generous 400 pages, I suppose the bounty had to come to an end somewhere.

With so much accomplished, Barbier remains very clear about her place in the history of Tarot history, as she says she is not a historian on par with “Michael Dummett, Mary K. Greer, Paul Huson, Robert Place, or Andrea Vitali who, among many others, spent decades working on these topics and whose work I admire greatly” (13). These are the authors, along with the “many others,” that Barbier honours her debt to in her select bibliography and notes. Such an honest and conscientious attitude is noteworthy in this age of internet pilfering and the careless elision of research and copying. Barbier’s contribution to Tarot studies is obviously grounded in a library researcher’s ability to distinguish good sources from bad, and primary from secondary sources, a good university student’s ability to summarize and restate accurately, and a professional artistic and authorial talent for innovative interpretation and the integration of verbal and visual material. Even so, she writes that

With great humility, I can admit that my work will always be biased. Although I have an academic background, I am a tarot reader, and the poetic eye will always prevail over the intellectual one. For this reason, this book isn’t encyclopedic, either—doesn’t pretend to show the most iconic examples nor the most historically relevant. Curated with the help of my own arbitrary sensibility I’m showing a collection of examples that I find fascinating for their beauty, the originality of their system, or the incredible story they tell. […] My ultimate intent was to showcase the great beauty and wealth of the cards and make them accessible to a wider audience, whether they are divination card enthusiasts or just amateurs of pretty pictures. (14)

It is a beautiful statement and one easily disputed. Short of website agglomerations of images or Stuart Kaplan’s four-volume Encyclopaedia of Tarot, this book is as much of an encyclopedia of Tarot images as one is likely to find in publication. Yes, the poetic eye makes a great advance apology for any disputes about deck or image selection, but without it there is nothing but a pool of Tarot images that is six centuries deep. The poetic eye recognizes patterns, distinguishes quality, marks the unique and unusual, and chooses or affirms what should be iconic in any given time. It is an ability that can become a skill, not an expression of short-coming or limitation. Limitations are what happens when book binding technology maxes out at 400 pages and only one volume is published instead of two. The poetic eye is what chooses the contents that will be meaningful within such required limitations.

All in all, Tarot and Divination Cards: A Visual Archive is a worthy companion to Kaplan’s Encyclopaedia and Pollack’s The New Tarot: Modern Variations of Ancient Images (1990). Prospective or veteran explorers of the visual history of Tarot can choose no better anchors for their study than these volumes. There are other valuable books on the subject and there will undoubtedly be more in the future, but as visual resources supported by accurate and useful text, these mark square one of the visual history of Tarot.

References

Pollack, Rachel. 1990. The New Tarot: Modern Variations of Ancient Images. Woodstock, NY, The Overlook Press.