Abstract

There are many familiar fairytale motifs in Marie de France’s lai titled Yonec. It has as its setting the wild fastnesses of northern Wales, and the sleeping knights of the tale, who wait in an otherworldly palace inside a hollow hill, suggest the resting place of Arthur and his knights of the Round Table. The bird/lover of Yonec’s mother, the title character’s true father in the story, presents the Lady (she never receives any other name) with assorted magical tools for her protection. These greatly resemble tokens granted to the heroines and heroes featured in the early Arthurian Welsh tales collected in The Mabinogion by Lady Charlotte Guest (1838–45). But earlier influences emerge also; Yonec, like Horus, is a redeemer who avenges the betrayal and murder of his divinely magical father. Another ancient resonance is the solar association of the hawk or falcon, as many of the human mothers of magical or divine saviour-sons conceive due to the quickening effects of the sun. This paper investigates the themes and motifs in Yonec, and their prevalence and diffusion in Europe after the early Crusades put the courts of Europe, Arabia, and the Levant in touch with each other. I also speculate upon the identity of Marie de France. Said to be the first woman novelist and the earliest known French woman poet, she is lauded as the most gifted poet writing in the lai form, yet there is still no consensus as to who she actually was. I offer up my favourites among the contending theories as to her origin and identity, and proffer a prose adaptation of the lai. This is prefaced by an introduction that conflates the leading speculations on the matter into one character. The narrator of my fictional offering presents a version of Marie de France who gets to inhabit all of the most popular legends surrounding her identity—that she was, variously, a countess, a nun, an abbess, or an educated noble courtier in the train of Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Methods and Keywords

I employed a multidisciplinary approach to this paper, incorporating Literary History, Medieval Studies, Cultural Studies, Mythology and Folklore Studies, the History of Emotions and Emotional Communities, Religious History and more to achieve a rounded discussion.

The Tale

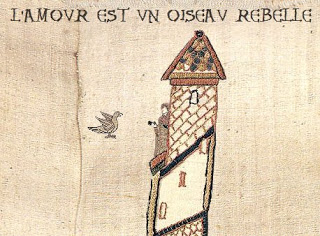

Yonec is the name given to the son of a shape-shifting fairy lover in Marie de France’s enigmatic, eponymous tale. The fairy lover, called Muldumarec, comes to the young and unfulfilled wife of a very much older, powerful, and wealthy man, regularly visiting her in her lonely tower where she has been incarcerated by her jealous husband. That unhappy union would seem to be the result of an arranged marriage, for which the author of the lai has little sympathy or respect. Muldumarec is eventually discovered and slain by the lady’s husband, which happens before the illicit lovers’ son is even born. When, many years later, his grave is discovered by the lovers’ now grown son, his mother (who never gets a name other than ‘the Lady’) instructs the lad to kill her (by now very aged and decrepit) husband, the man the boy has up until this moment regarded as his father. This murderous errand he promptly accomplishes with the use of a magical sword set aside for him from birth by his lady mother, it having come down to him from his supernatural father. Yonec is half fairy and therefore seemingly absolved from the normal moral framework of Church, society, and state, and so acts upon the following injunction from his mother with all alacrity and aplomb. The slain husband receives no sympathy from anyone in the story, while Yonec is celebrated for having dispatched the old man “nobly” in a divine retribution endorsed, in the lai, by God:

Yonec is the name given to the son of a shape-shifting fairy lover in Marie de France’s enigmatic, eponymous tale. The fairy lover, called Muldumarec, comes to the young and unfulfilled wife of a very much older, powerful, and wealthy man, regularly visiting her in her lonely tower where she has been incarcerated by her jealous husband. That unhappy union would seem to be the result of an arranged marriage, for which the author of the lai has little sympathy or respect. Muldumarec is eventually discovered and slain by the lady’s husband, which happens before the illicit lovers’ son is even born. When, many years later, his grave is discovered by the lovers’ now grown son, his mother (who never gets a name other than ‘the Lady’) instructs the lad to kill her (by now very aged and decrepit) husband, the man the boy has up until this moment regarded as his father. This murderous errand he promptly accomplishes with the use of a magical sword set aside for him from birth by his lady mother, it having come down to him from his supernatural father. Yonec is half fairy and therefore seemingly absolved from the normal moral framework of Church, society, and state, and so acts upon the following injunction from his mother with all alacrity and aplomb. The slain husband receives no sympathy from anyone in the story, while Yonec is celebrated for having dispatched the old man “nobly” in a divine retribution endorsed, in the lai, by God:

Dear son, now do you but hear

How God above has led us here!

Here lies your father, and my true

Love, this wretch [her husband] wrongly slew.

Yet you shall wield his sword anew,

That I have long guarded for you.’

[…] Ere leaving, Yonec they did afford

All honour, and made him their lord.

Who heard the tale, they made a lay

A long time after, nearer our day,

All the pain and woe to record,

That for love those two endured. (Marie de France, 2019, pp.112-113)

There are many familiar fairytale resonances and motifs in the lai of Yonec. There is the Rapunzel-like internment of the heroine where she is jealously guarded in a tower, and the sleeping knights in the other-worldly palace inside the hollow hill suggests the resting place of Arthur and his knights (the legend is that they will rise again at Britain’s time of greatest need). The bird/lover presents Yonec’s mother with a ring and a cloak. The ring, like the knot, is a symbol of eternity and constancy, and the cloak is an ancient symbol of protection. The cloak affords a kind of immunity and a certain invisibility in many an old story, as it does for the woman in this tale, who is thereafter no longer interfered with. As the son of true love, Yonec, like Horus, is a redeemer and avenger. He ultimately gains restitution for his father who, like the father of Horus, was slain by treachery. This is an extremely archaic “redeemer” profile. It features in reverse form (the female is the sacred animal) as early as the Hittite tale, Master Good and Master Bad (Bronner, 2017, p.85), with equivalent images across the ancient world. Another ancient resonance is the solar association of the hawk or falcon, as many of the human mothers of magical or divine saviour-sons conceive due to the quickening effects of the sun.

The Author’s Identity

There are, it seems to me, two important questions to answer before delving into these timeless motifs as they are represented in the lais of Marie de France. One concerns the identity of this writer, said to be the first woman novelist and the earliest known French woman poet. She is lauded as by far the most gifted poet writing in the lai form, “perhaps the greatest woman author of the Middle Ages and certainly the creator of the finest medieval short fiction before Boccaccio and Chaucer” (Spiegel, 1994, p. 3). There are those who think that it was Marie de France who actually established and immortalized the fame of Breton story-forms. By her day, in the late 12th century, the Bretons already had a reputation for story-telling, a reputation which clearly owed much of its currency in the later Middle Ages to Marie de France. It is likely that her shorter tales were distinguished by a particular musical form, that of a short lyrical composition sung to a harp or a rote (Burgess and Busby, 1986, p.8). They showed a clear predilection for love and the supernatural in subject matter, and many of them had their setting in Celtic strongholds of Brittany or Wales. By the time such tales were written in English, that is, in the fourteenth century, references to the lais of the Bretons are conventional references.

There are, it seems to me, two important questions to answer before delving into these timeless motifs as they are represented in the lais of Marie de France. One concerns the identity of this writer, said to be the first woman novelist and the earliest known French woman poet. She is lauded as by far the most gifted poet writing in the lai form, “perhaps the greatest woman author of the Middle Ages and certainly the creator of the finest medieval short fiction before Boccaccio and Chaucer” (Spiegel, 1994, p. 3). There are those who think that it was Marie de France who actually established and immortalized the fame of Breton story-forms. By her day, in the late 12th century, the Bretons already had a reputation for story-telling, a reputation which clearly owed much of its currency in the later Middle Ages to Marie de France. It is likely that her shorter tales were distinguished by a particular musical form, that of a short lyrical composition sung to a harp or a rote (Burgess and Busby, 1986, p.8). They showed a clear predilection for love and the supernatural in subject matter, and many of them had their setting in Celtic strongholds of Brittany or Wales. By the time such tales were written in English, that is, in the fourteenth century, references to the lais of the Bretons are conventional references.

Unfortunately, one can’t say with any certainty which of several candidates for this illustrious stature was the actual Marie de France, who appears to have lived in Norman England and been connected with the court of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Henry II of England (Spiegel, 1994, p.4). Illegitimate royalty, nuns, abbesses, and noble wives, all called Marie, have been put forth as the ground-breaking author. Marie de France has also been tentatively identified with Mary, abbess of Shaftesbury. My favourite explanation as to her true identity is that she was the eighth child of Waleran de Meulan (or Waleran de Beaumont), a nobleman of a great Norman house. “Waleran’s fief was in the French Vexin, which would tally with Marie’s statement that she comes from France and explain her evident local knowledge of the town of Pitres in the Norman Vexin” (Burgess and Busby,1986, p.18). This Marie married Hugh Talbot, who was baron of Cleuville and who owned lands in Herefordshire and Buckinghamshire as well as Normandy. He was also related to prominent families in several other English counties, including Devonshire, Gloucestershire, and Kent. Marie de Meulan’s father was a fighting man, a soldier who is thought to have also written Latin verse. Geoffrey of Monmouth, a historian steeped in Breton Celtic lore, dedicated several manuscripts of his Historia Regum Britanniae to Waleran de Meulan, as well as to a William who may have been Marie’s patron.

The reason I think this is the real Marie, and not those twelfth-century candidates who lived as nuns or abbesses, is that her writings are so steadfastly, if mildly, heretical. This affiliates her, I think, with the formal conventions and philosophies of the so-called Courts of Love of Provence and Occitania (formally declared heretical by Pope Innocent III in 1206 and targeted for destruction in the Albigensian Crusade). This literary tendency, as we have seen, is not unusual, even in educated or visionary churchwomen, but the voice of Marie de France seems to emanate from a different experience, allegiance, and style of life than that of the abbess or nun. While there appears to be some possible familiarity with the monastic life (perhaps a convent education) in Le Fresne, Yonec, and Eliduc,

[…] the prominence of the motif of adultery in the Lais (see also fables 44 and 45), Marie’s attitude towards the dissolution of marriage in Le Fresne and Eliduc, and her evident interest in the chivalric life suggest that these love poems were not written by someone steeped in ecclesiastical ideology. (Burgess and Busby, 1986, p. 18)

She stoutly defends the values and principles of chivalry, including the jousting and noble burial for those killed in jousting, both forbidden at the time by church law.

Adultery, Coarse and Refined Love in Yonec

In Yonec, the shape-shifting Muldumarek insists that, when her priest comes to give her communion, he will magically assume her shape and take the holy wafer and wine in her stead. He hopes by doing this to prove he is a Christian and not a devil. This kind of ploy is one commonly attributed to the fairies themselves, and seems to establish Muldumarek as the Fairy King. Except when Yonec’s fey falcon-father demands to prove his virtue by taking the sacrament of the transubstantiation, there is no mention of standard religious observances, which, with so many Church affiliations among the courts, the aristocracy, and royalty, would seem to at least require lip-service. This one sacramental motif may have been included to serve as a prophylactic for the many other overtly pagan themes developed in this and other lais attributed to Marie. Although adultery occurs in several forms its most common manifestation is that of the knight and the married woman, the medieval metaphor for the goddess and her lover which we are used to seeing in the stories of Venus and Adonis, Astarte and Tammuz, Nerthus and her priest, Helen and Paris, Grainne and Diarmatt. Another possible reason for the motif’s inclusion may have been due to the lack of conflict between the concepts of sacred blood, miraculous transformation, and the Grail mysticism of the Courts of Love. Marie de France, unlike the churchman Chrétien de Troyes, had a real taste for these typical motifs of what was sometimes considered the (uniquely) Western “left-handed path” of amor (Campbell, 1990, p.210). With only the slightest tribute paid to ecclesiastical ideology, she seems to have upheld “the love that exists most privately between couples, who are absolutely free in their love from any consideration of loss and gain, who defy society and transgress the law and make love be the be-all of life” (Dasgupta, 1969, p.124).

Of the thirteen lais known to be by Marie of France seven deal directly with an adulterous situation, and one indirectly. Their evocation of marital freedom is informed by the Celtic myths which lie behind the romances. In them we also find the pre-Christian, matrifocal social convention that it is very often the woman who desires and makes the first advances. The amorous lovers in the lais often conceive an undying passion with just one glimpse of the beloved, or even simply from their description, a phenomenon of “love at first sight,” the subjective experience exalted by the troubadour Giraut de Borneil, “Love is born of the eyes and the heart”. Unlike Eros or Agape, both of which are impersonal and undiscriminating, Marie’s courtly amor represented women as significant persons, where “the woman was almost always of equal or superior rank and honored for and as herself” (Campbell, 1990, p.210). This pattern elevated the free and liberated love of women to the status of divinely ordained, perfect, ethical, and honorable love, similar to that espoused in the early (first five centuries) Christian “Agape love feasts” of Gnostic sects. “And there can be no doubt that in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Europe, the period of the Troubadours, there developed in certain quarters of the rampant Albigensian heresy a formidable resurgence of this type of religious thought and practice” (Campbell, 1990, p.210).

Sin and Purity, Demons and Spirit Spouses

Some have argued that the lyric poetry (and cult) of amor proliferated by Marie de France and other writers of courtly Romance, as well as the troubadours and trobairitz of the Provençal Courts of Love, was a by-product of this “Church of Love” (Campbell, 1990, p.211). Joseph Campbell posited that Marie was similar to the minnesinger Gottfried von Strasburg (c. 1210), who opens “a religious dimension within secular literature” (in the Tristan and Iseult cycle), with his ecstatic (if dangerously heretical) devotion to the goddess Minne (“Love”), whose model for the sacrosanct purity of love is a chapel built by pagan giants in ancient times.

And then, moreover, to ensure his point, when the lovers flee to the forest, he brings them to a secret grotto of the goddess, described explicitly as an ancient heathen chapel of love’s purity, and with a bed—a wondrous crystalline bed—in the place of the Christian altar. (Campbell, 1990, p.212)

Campbell observes that the Grail legend, also, had sprung from that pagan base.

The particular way in which Marie employs the grail/communion motif is extremely mystical and very pagan in style, insomuch as an apparent avatar of a solar hawk or falcon god (like Welsh Llew Llaw Gyffes, Egyptian Horus, or Babylonian Ashur) shape-shifts into the female form of his beloved in order to defraud the priest and receive the sacrament in disguise, thus adding trans-gender shapeshifting magic to his list of “sins.” By rights (Christian rights, that is), he should have made confession of his sins before receiving the sacrament; intending to sleep with his neighbour’s wife would definitely have been considered one of them. Of course he would have had to have been a good, Christian, mortal, instead of a magical, shape-shifting, moral atavism in order to have any kind of developed sense of sin in the first place. Added to this amorphous moral landscape is the fact that birds have been seen as symbolizing the soul from time immemorial, long before Christianity, extending back to prehistoric religious depictions. Marie herself, refreshingly, seemed to have no clearly developed sense of Christian (or even non-denominational patriarchal) sin. She demonstrated a highly refined moral sense and ethicality in the lais, but it was of a different order than that promoted by the church. If she had gravitated to a church-sponsored accounting of the supernatural visitor in Yonec, she would not have had to have looked farther than the exacting demonologies of her time. She would have been familiar with the early Middle English poet, author of the romance-chronicle the Brut, considered one of the most notable English poems of the 12th century. The Brut’s Arthurian section tells the tale of Merlin’s conception from the demonic spirit lover of his mortal mother, said by some to have been a dragon—specifically the Red Dragon of Wales:

I know full well hereon. There dwell in the sky many kind of beings, that there shall remain until domesday arrive; some they are good and some they work evil. Therein is a race very numerous, that cometh among men; they are named full truly Incubi Daemones; they do not much harm, but deceive the folk; many a man in dream oft they delude, and many a fair woman through their craft childeth anon, and many a good man’s child they beguile through magic. And thus was Merlin begat, and born of his mother, and thus it is all transacted. (Layamon, 1999, pp.31-32)

Audiences and the Nature of Fairytales

In the immortalized view of Marie de France’s contemporary, rival, and perhaps her harshest critic, Denis Piramus (12th c.), “Marie’s poetry has caused great praise to be heaped on her and is much appreciated by counts and barons and knights who love to have her writings read out again and again” (Burgess and Pratt, 2006, p.208). The lais represented scripts by which amateur orators could tell ancient tales without the investment of time for memorization, the many years of study required of a bard (skald, storyteller, or shaman), or the musical or vocal training required of a troubadour, trobairitz, minnesinger, trouvere, or jongleur. Neither professional performers nor members of an ancient priestly caste, amateurs could recite, with Marie’s little volume of verses, at court or country estate. The lais were probably organized so as to alternate longer ones with shorter ones, so two could be read out in any given performance. The group dynamic of commonly received lore, of the love-stories of demigods and mortals, could return to its central, popular, and populist role in court culture, in such a manner as it may not have enjoyed since the mead-hall recitations of ancient bards (or the fireside, story-telling wise-women and shamans who preceded them).

Outside of the nursery, group story was, by the twelfth century, administered mainly by professional secular entertainers, and their audiences were passionately interested in the practice and theory of the refined kind of love such as Marie treats in the lais. They would have seen their own world mirrored in Marie’s fictional one, with recognizable place names and settings, familiar right up to the moment the enchanted animal starts talking or the noble bird transforms into a strikingly handsome naked man. The audiences for these tales,

were of exalted rank, lived in castles, rode horses in forests, participated in tournaments and had love-affairs. Here again, the fairy-tale element may be visible if we are to regard the lais at least partly as wish fulfillment for a particular social class.” (Burgess and Busby, 1986, p.34)

The other question I’d like to address concerns the nature of fairy tales. What did they represent to the society of the twelfth century, those fairy stories of Dame Marie which excited rival Denis Piramus’ sour description of “lais in verse which are not at all true”? What do they represent now, to technological society and individuals? What, exactly, have fairy tales ever represented, with their totem ancestors, fairy godmothers, magical or divine patrons, magical “power” objects, sacred “power” sites, and numinous symbols? What do they accomplish in their inexhaustible power to fascinate, suspend disbelief, and transform? What is the significance of the persistent, vestigial traces of ancient shamanic trance practices and spiritual journeying in their ability to entrain and entrance? In The Flight of the Wild Gander, Joseph Campbell comes right out and says, “This is the story our spirit asked for; this is the story we receive,” and even, “The folk tale is the primer of the picture language of the soul.” He also presents a more technical theory propounded by the French sociologist Emile Durkheim:

He argued that the collective superexcitation (surexcitation) of clan, tribal, and intertribal gatherings was experienced by every participating member of the group as an impersonal, infectious power (mana); that this power would be thought to emanate from the clan or tribal emblem (totem); and that this emblem, therefore, would be set apart from all other objects as filled with mana (sacred versus profane).This totem, this first cult object, would then infect with mana all associated objects, and through this contagion there would come into being a system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, unition in a single moral community all believers.

This is not a complete answer by any means, but it approaches the subject from an enlightened standpoint. The great contribution of Durkheim’s theory, and what set it

apart from all that had gone before, was that it represented religion not as a morbid exaggeration, false hypothesis, or unenlightened fear, but as a truth emotionally experienced, the truth of the relationship of the individual to the group. (Campbell, 1990, p.32)

In her study of fairy tales and folklore of 1980, Maureen Duffy examined The Erotic World of Faery, coming to the conclusion that whenever fairies, elves, or imps appear in stories spanning the past fifteen hundred years or so, we have strayed into the realm of repressed sexuality. This neat and somewhat Freudian analysis fails to take into account the sacred elements of folk and fairy tales, however, as domesticated shaman stories and visionary journey narratives. It also fails to account for the role of fairy tales in dealing with the inexorable, irreligious forces of death, the seasons, or the cyclical personal and collective thresholds of psychic transformation broached through wonder tales and folkloric motifs. Like the modern day genres of Fantasy and Science Fiction, fairy tales have always included all of these elements, and their most significant role would therefore be more accurately evaluated as that fulfilled by transformation tales, in keeping with their clear role and function in cultures and societies far from Western Judeo-Christian strictures on sex and sexuality or the need to sublimate them.

Ambivalent Moral Landscapes and Divine Sons

Boldly and fearlessly Gilgamesh entered the tunnel, but with every step he took the path became darker and darker, until at last he could see neither before nor behind. Yet still he strode forward, and just when it seemed that the road would never end, a gust of wind fanned his face and a thin streak of light pierced the gloom. When he came out into the sunlight a wondrous sight met his eyes, for he found himself in the midst of a faery garden, the trees of which were hung with jewels. And even as he stood rapt in wonder the voice of the sun-god came to him from heaven. (Leeming, 1998, p.125)

With Yonec we return once again to the spirit-spouse or bird/lover of the Psyche and Eros tales, with definite Cinderella elements. Like The Lover Who Came as a Star, Muldumarec arrives on the wing, entering through the window. Like all amorous, avian, winged Eros figures of fable and fairy tale, he will stop at nothing to make his beloved his own. And the heroine of this tale, a latter-day Psyche, will stop at nothing in order to bring Love and Spring, Truth and Beauty, Life and Renewal back into the world, even if over the dead body of her husband.

References

Bogin, Meg (1976). The Women Troubadours. Paddington Press, New York.

Bronner, Simon J. (2017). Folklore: The Basics. Routledge, New York.

Burgess, Glyn S. and Busby, Keith. ‘Introduction,’ in France, Marie de. (1986). The Lais of Marie de France, trans. Glyn S. Burgess and Keith Busby. Penguin, London.

Burgess, Glyn S. and Pratt, Karen, eds. (2006). The Arthur of the French: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval French and Occitan Literature. University of Wales Press, Cardiff.

Campbell, J. (1990). The Flight of the Wild Gander: Explorations in the Mythological Dimension Selected Essays 1944-1968. Harper Collins, New York.

Dasgupta, S. B. (1969). Obscure religious cults. Calcutta.

Duffy, Maureen (1980). The Erotic World of Faery. New York.

Spiegel, Harriet. ‘Introduction.’ in France, Marie de. (1994). Fables, ed. and trans. Spiegel, Harriet. Toronto University Press and Medieval Academy of America, Toronto.

France, Marie de. (2019). ‘The Twelve Lais, Part III: The Lays of Yonec, Laüstic (The Nightingale), and Milun’. trans. A. S. Kline. Poetry in Translation. Stable URL: https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/French/MarieDeFrancePartIII.php

Layamon (1999). The “Arthurian” Portion of the Brut. Trans. Sir Frederic Madden, K.H. In parentheses Publications, Middle English Series. Cambridge, Ontario.

Leeming, David Adams (1998). Mythology: The Voyage of the Hero. Oxford University Press, New York and Oxford.

Piramus, Denis (12th c.). La vie saint Edmund, ed. H. Kjellman, repr. Geneva 1974.

Yvonne Owens is a past Research Fellow at the University College of London, and Professor of Art History and Critical Studies. She was awarded a Marie Curie Ph.D. Fellowship in 2005 for her interdisciplinary dissertation on Renaissance portrayals of women in art and sixteenth-century Witch Hunt discourses. She holds an M.A. in Medieval Studies with Distinction from The Centre For Medieval Studies at the University of York, U.K., and an M.Phil. and Ph.D. in History of Art from University College of London. Her publications to date have mainly focused on representations of women and the gendering of evil “defect” in classical humanist discourses, cross-referencing these figures to historical art, natural philosophy, medicine, theology, science and literature. Her book, Abject Eroticism in Northern Renaissance Art: the Witches and Femme Fatales of Hans Baldung Grien, Bloomsbury London, came out in 2020. She also writes art and cultural criticism, exploring contemporary post-humanist discourses in art, literature and new media. Dr. Owens has recently contributed two essays as forewords to artists’ books published by Gagosian Gallery, titled “Time Travelling in Rachel Feinstein’s Mirror” (2022), and “The Two Anna Weyants” (2023). She is the editor for an anthology of essays titled Trans-Disciplinary Migrations: Science, the Sacred, and the Arts.

Yvonne Owens is a past Research Fellow at the University College of London, and Professor of Art History and Critical Studies. She was awarded a Marie Curie Ph.D. Fellowship in 2005 for her interdisciplinary dissertation on Renaissance portrayals of women in art and sixteenth-century Witch Hunt discourses. She holds an M.A. in Medieval Studies with Distinction from The Centre For Medieval Studies at the University of York, U.K., and an M.Phil. and Ph.D. in History of Art from University College of London. Her publications to date have mainly focused on representations of women and the gendering of evil “defect” in classical humanist discourses, cross-referencing these figures to historical art, natural philosophy, medicine, theology, science and literature. Her book, Abject Eroticism in Northern Renaissance Art: the Witches and Femme Fatales of Hans Baldung Grien, Bloomsbury London, came out in 2020. She also writes art and cultural criticism, exploring contemporary post-humanist discourses in art, literature and new media. Dr. Owens has recently contributed two essays as forewords to artists’ books published by Gagosian Gallery, titled “Time Travelling in Rachel Feinstein’s Mirror” (2022), and “The Two Anna Weyants” (2023). She is the editor for an anthology of essays titled Trans-Disciplinary Migrations: Science, the Sacred, and the Arts.