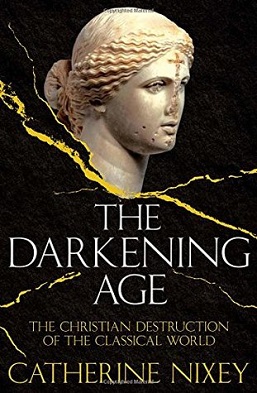

The events described at the very start of Catherine Nixey’s first book feel eerily contemporary. What Nixey describes, however, is not the destruction of World Heritage sites like Nineveh by the Islamic State or Bamiyan’s Buddhas by the Taliban. It is the destruction and deliberate desecration of Roman Palmyra’s temple of Athena-Al’Lat in the late 380s CE. At that time, a band of early Christian zealots invaded this temple, struck the monumental cult statue so hard that the marble head fell off. The rest of the statue swiftly followed suit, being knocked off its pedestal, its arms struck off (pp. xvii-xix).

The events described at the very start of Catherine Nixey’s first book feel eerily contemporary. What Nixey describes, however, is not the destruction of World Heritage sites like Nineveh by the Islamic State or Bamiyan’s Buddhas by the Taliban. It is the destruction and deliberate desecration of Roman Palmyra’s temple of Athena-Al’Lat in the late 380s CE. At that time, a band of early Christian zealots invaded this temple, struck the monumental cult statue so hard that the marble head fell off. The rest of the statue swiftly followed suit, being knocked off its pedestal, its arms struck off (pp. xvii-xix).

Likewise, the reader can be forgiven for likening Nixey’s description of the appearance and behavior of this mob to that of the mob that descended upon the United States Capitol on January 6, 2021. That, too, was “violent work, but … by no means solemn.” Laughter, jeers, chants characterized both mobs. Compare the chants “Shameful things … demons and idols…” with the chants of “Where’s Nancy?” and “Hang Mike Pence!” and one can see the similarities in what zealotry can cause.

Nixey’s painstaking work relies heavily upon contemporaneous documents, such as saints’ lives, classical philosophy, martyrologies, and ancient Roman writers such as Tacitus, Pliny the Younger, and Juvenal, along with more modern historical scholarship. Rooted in a Roman Catholic upbringing (the author’s parents are a former nun and former monk) and marked by the eminently fair observation that monasteries preserved some scholarship of the ancient world, Nixey’s research delves deeper, to the reality that the actions of zealots destroyed even more than could be preserved. The “triumph of Christianity” writes Nixey, was, ironically, a true Roman triumph (p. xxvi). Let us consider the example of the conquest of Gaul and the triumphal arches that commemorate Roman victories in now-French cities like Saintes, Reims, and Orange, and the processions in Rome itself. These arches serve as a visual reminder of conquest. Roman triumphal processions included not merely the victorious general and his troops, but chained, enslaved captives paraded through the streets of the capital city. A triumph, in the Roman milieu, was, as Nixey notes, about total defeat, subjugation, and the annihilation of the losers. Nixey has the education to back up these assertions. She is a Cambridge-educated scholar of Classics who taught in the field prior to her turn to journalism.

Hence the monkish selectivity in copying those works they deemed worthy of saving, and neglecting those, such as produced by Celsus and Democritus, that they deemed heretical (pp. 35, 39-40). Heresy, as a sin, poses the threat of endangering the Christian soul with damnation and eternal torment in Hell. Thus, any such work that threw into question simple belief in the divine creation of the Earth, or dared to propose rational notions such as Democritus’s atomic theory, had to be suppressed. How might we then compare this to the efforts of ultra-conservatives to ban books in school libraries, label Renaissance masterpieces such as Michelangelo’s David as pornography, silence discourse on LGBTQIA/2S rights, and outlaw the medically supervised procedure of abortion? Iconoclasm as a phenomenon includes the destruction of cultural and social norms, intellectual ideas, and spirited debate, not just the destruction of images.

When Nixey goes on to discuss the real, historical actions of Pliny the Younger as the governor of a Roman province and of other prefects, the contrast between historical reality and the usual depiction of Roman officials as persecutors of devout, innocent early Christians crumbles. Instead, a new portrait builds: Pliny the Younger upholds his responsibilities as an appointed government official. His job, first and foremost, is to see to the security and prosperity of the region under his supervision. Far from a bloodthirsty, lascivious tyrant, Nixey reveals a moderate, temperate man who must uphold the law and yearns to demonstrate mercy. For his pains, a young woman spits in his face, demanding torture and death. A retired soldier rejects all prefect Maximus’s attempts at compromise, even with his pension’s restoration in full offered as enticement. He too prefers martyrdom to peaceful coexistence (pp. 71-86).

The iconoclastic zealots Nixey discusses do not merely seek their own deaths; they also mete it out. The hideous death the zealots dealt the aging philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria springs instantly to mind (p. 145-146). The atrocities described seem ripped from the headlines of newspapers covering violent religious radicalism in such troubled places as Sudan, Afghanistan, Iran, or scholarship on Europe’s early modern Wars of Religion. Why this violence, this intolerance? Nixey states quite bluntly, “For those who wish to be intolerant, monotheism provides very powerful weapons” (p. 103).

The theological underpinnings of this violence, asserts Nixey, lay in the Book of Deuteronomy with its instruction to raze sacred groves, melt down or break sacred images, and demolish temples (p. 25). What the fanatics considered to be a violent but necessary purgation of spiritual pollution was seen by Pagan clergy and faithful worshippers, and by the erudite philosophers who embodied everything the Classical World deemed civilized, as desecration. From this sort of violence, it was no leap at all to attack, physically, fatally, the adherents of a polytheistic religion.

Nixey’s assertions deny any possibility of survival of the earlier faith traditions. There is more than a grain of truth to this. Traditional folkways are not the same as fully fleshed-out theologies. Still, the survival of the cunning man and wise woman traditions in the British Isles, the continuation of the tarantella in Sicily, the Maypole dances, and what Evans-Wentz aptly named the faerie faith (W. Y. Evans-Wents, The Fairy Faith in Celtic Cultures, 1911) across northern Europe, among many others, points out how fragile these remnants of ancient forms of worship were.

Nixey makes a point that we, as modern Neopagans – Wiccans, Druids, Heathens, and others – might wish to consider: “Pagan” was a term of insult in the later, Christianizing Roman Empire, akin to the American English terms “redneck” and “hillbilly” for poor, uneducated, rural white Americans (p. xxxiv-xxxv). Like the six-letter N-word, “pagan” was meant by Christians as a gross insult of their polytheistic contemporaries. If we are to use it, we should do so knowing full well what it meant anciently, so that we may reclaim it more thoroughly.

The Darkening Age makes for grim reading. It can be difficult to take in the levels of violence that accompanied the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity, just as it is mind-numbing to contemplate any systemic political, communal, or genocidal oppression. From the unsparing description of the murder of Alexandrian philosopher and mathematician Hypatia by a mob of Christian zealots, to the heartbreaking story of the closure of Athens’ justly famous Academy, with Shenoute’s brutalities and Justinian’s decrees ordering the execution of recalcitrant Pagans thrown into the mix, this is a deeply frightening book for anyone on a Neopagan path. Yet this is necessary reading. Violent religious zealotry permeates human societies as much now as it did nearly 1,700 years ago. Indeed, it has recurred with alarming regularity over nearly two millennia. No society, no culture, no faith community has been immune. Indeed, we may be witnessing our own darkening age. We would all do well to read this book carefully, take its lessons to heart, and strive endlessly to prevent any repetition of such suppression. The magnificent cultural institutions of the Classical age went under not because philosophers, ordinary believers, and the clergy found them spiritually and intellectually unsatisfying. They vanished because their adherents were terrorized into silence and submission. Resistance is necessary and required, always.