Introduction

Yvonne Owens and Toyin Adepoju have been discussing magic, Ifa Tradition, art, sexuality, gender, witchcraft, Western Esotericism, embodied spirituality, and other spiritualized topics for over fifteen years after meeting at a Classical Reception conference at The School of Advanced Study, a postgraduate institution of the University of London, in 2005. Soon after meeting, they presented a joint paper at a postgraduate conference titled Crossing Places that took place at the University of Nottingham from the 26th to 27th of January 2006. This was an interdisciplinary conference showcasing research on topics concerned with Africa.

Toyin’s and Yvonne’s presentation took the form of a disputation with the aim of leading to a synthesis and resolution on some thorny issues, within both traditions, concerning sexuality and the sacred. It was fundamentally a literary performance by a Welsh witch and an African scholar of the esoteric Ifa Tradition. Their joint paper generated great interest at the conference, and led to several invitations to publish, including a recent one from Cambridge Scholars Press to publish their research in a co-edited scholarly anthology of like-minded researchers.

This work, titled Trans-Disciplinary Migrations: Science, the Sacred, and the Arts, is due out sometime in 2022, with the editors’ joint and individual chapters furthering the collaborative investigations that began with the seminal/ovarian discourse presented here. The book will also feature contributions by a core group of scholars whose research and writings focus, similarly, on the intersections of science, healing, wellness, the arts, and the sacred world. Exploring how the sacred, the arts, and sciences may implicate each other at the level of creative methods, modes of understanding and expression, essays include rethinking the sacred in order to highlight it as a pervasive quality of human experience, noting the strong emergence of the sacred in contemporary science.

The Disputation

Toyin: I am intrigued by your idea about relationships between feminine biology, particularly menstruation and the development of human consciousness. Although it seems to be me that you are overstretching your case there in a determined, perhaps even desperate effort to valorise the biology of you and your sisters in response to all the persecution you have suffered all these years

Yvonne: Frankly speaking. Look at it. Sexual drive is one of the most fundamental of human drives. The argument I am making relates in a fundamental way to this drive.

Toyin: Please go over it again.

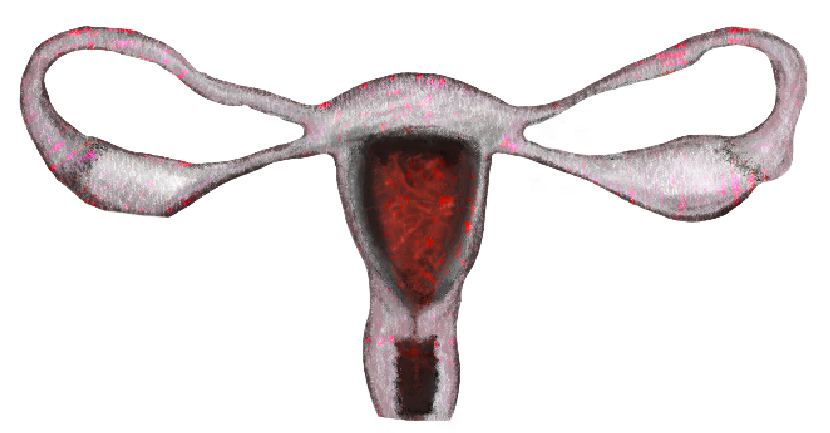

Yvonne: I am arguing that the peculiar structure of female menstruation is fundamental to the manner in which human consciousness has developed. I think that the fact that the human female’s menstrual cycle enables the possibility of sex at all phases of the biological cycle, unlike the estrus cycle in other mammalian species, is significant not only in terms of human reproductive biology, but also in terms of human consciousness. Historically, this singular fact has been enormously influential in human constructions of the sacred. Other animals can only have sex at particular phase of the female’s cycle. The potentials inherent in this range of possibility with the human female foregrounds the question of choice. Do we, or do we not do it, and in what context? The presence of choice in the human psyche, particularly when it operates not just in relation to the individual but to the entire social group, constitutes humanity–implies necessarily a quantum development in the human character of complexity in human social and individual consciousness. Ethical norms, modes of dress, artistic and philosophical and even scientific achievements relating to sex could all be said to relate directly to the potential of choice opened up by this possibility.

Toyin: Go on…

Yvonne: Ethical standards that regulate sexual life have grown in complexity because of the unpredictability of desire and the possibility of its gratification. Massive libraries of literature, and of various artistic forms respond to the vagaries, paradoxes and unpredictability associated with sexual desire and its possible gratification.

Toyin: And you think that all this emerges from the capacity of the female to have sex at any point of her menstrual cycle? Since her capacity for sex is what attracts the male in the first place?

Yvonne: Yes. In other animals sexual desire does not arise in the male at just any point in the biological cycle of the female. It emerges only at the point when she secretes particular hormones that indicate that she is available for sex. But it’s not so with humans. The fact that the female may be theoretically ready at any point of her cycle indicates and enables the response of the male at any point of the cycle.

Toyin: I would expect you are not describing sexual desire and response as something automatic, that emerges with compete instinctiveness and is uncontrolled by the mind and the host of social codes that regulates human behaviour.

Yvonne: Certainly not. I am describing a theoretical possibility of the emergence of desire and of response to that emergence. Of course it is this very possibility that amplifies the development of mechanisms of choice, of selectivity in both men and women–that I argue has contributed fundamentally to the complexity of human consciousness. Greater availability implies the development of choice, of means of regulating and ordering choice.

Toyin: Intriguing. It does have coherence. But don’t you think you are making male sexuality overly dependent on that of the female. At least, even though humans share characteristics with animals, they really cannot be called animals, only their relatives at best.

Yvonne: I doubt that I am overemphasizing that dependence, as you call it. And humans are primates. We are animals.

Toyin: I would think that this theory of yours needs to be examined in terms of empirical study of the chemistry of human sexual development and attraction. I wonder if the process of attraction and response is as direct and unequivocal as your ideas seem to suggest.

Yvonne : I am working on that scientific aspect of the study. I do agree that I would need to examine the theory in the light of empirical study in relation to human chemistry.

Toyin: I would think, though, that the theory does demonstrate a significant degree of internal consistency and of correlation with actual human experience. Your construction of such an idea implies that the conceptions of the feminine have come a long way from its demonisation in Western culture.

Yvonne: Sure! Many cultures describe female biology, particularly female body fluids and the menstrual process in particular in terms that indicated it as unclean and/or dangerous. Women, in these contexts, are treated as creatures under what was known in Europe as the “curse”, whenever they had their periods. When, in fact, that very “curse” was vital not only to the possibility of procreation in indicating what

points in the biological cycle where procreation was possible but was symbolic of vital network of possibilities in relation to sex that has been so vital for the development of our species.

Toyin: In the Yoruba traditional thought from Nigeria, which I am studying, menstrual fluid is also described as dangerous to the consecrated sacred space used in religious activity.

Yvonne: So similar to Judeo-Christian constructions. The art of Albrecht Dürer’s most famous apprentice and close friend, Hans Baldung Grien, exploits these deadly prejudices by depicting women in forms that ground the medieval conception of the witch in terms of menstruating women.

Toyin: Wait. Please go over that again. Are you stating that images of witches were characterized in terms drawn from female menstruation?

Yvonne: Yes. In the work of certain seminal Renaissance artists, anyway.

Toyin: How?

Yvonne: Well, in the famous case of Baldung, his witchcraft images helped to establish the abject/erotic stylizations and feminine iconography of witches in art.

Toyin: How did that happen?

Yvonne : Baldung deployed radically polarized images of desirability and abjection as an affective visual strategy in his witchcraft images.

Toyin: Striking paradoxes. “Desirability” and “abjection.”

Yvonne: Yes. In Baldung’s figures of women and witchcraft, intimately engaging imagery and attractive, pornographic display are set against icons of monstrous acts and ‘polluted,’ feminine, genital emissions.

Toyin: How horrible.

Yvonne: Absolutely. Baldung balanced attraction against fear, revulsion against desire, and charged eroticism against abject horror.

Toyin: An attitude that recurs in various images of the feminine.

Yvonne: Yes. His images of the corrupt and corrupting feminine body reflected many elite discourses concerning corporeal, feminine evil in currency among both classical humanists and conservative scholastics in early 16th-century Germany, which gendered witchcraft as a naturalized product of “feminine defect.”

Toyin: Really?

Yvonne: True. In constructing his detailed and highly influential iconography of witchcraft, Baldung gave powerful visual expression to Late Medieval tropes and stereotypes and traded on their popularity. Themes that referenced and reflected themes of feminine ‘pollution,’ such as the Poison Maiden, Venomous Virgin, Ages of Woman, Fall of Man, End Times, and Death and the Maiden motifs, became his stock-in-trade.

Toyin: And yet he was giving shape to older ideas?

Yvonne: Yes. These ideas had roots in classical representations of feminine sexuality which derived from Aristotelian Natural Philosophy.

Toyin: Aristotle?!

Yvonne: Certainly. This philosophy shaped medical and theological discourses, becoming central to 16th-century Witch Hunt typologies in Germany, and to their gendered characterizations of maleficia.

Toyin: How would you sum up their thrust?

Yvonne: They painted a picture of woman’s inferior nature as an imperfect reflection, or ‘inversion,’ of the masculine, which contributed to her depravity and perversity. The evident sign of this was menstruation, among a wide cross-section of related signifiers.

Toyin: Amazing. What strikes me here is the possibilities in cultural interpretation suggested by the development of the demonizing image of the female in Judeo-Christian thought. We could correlate that theory of yours about consciousness in relation to sexual choice as arising in relation to female biology to the Biblical story of Eve initiating human knowledge of good and evil, of the recognition of difference between the human and nature that emerged when they realised they were naked after eating the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.

Yvonne: Go on…

Toyin: In relation to your theory that story takes on overtones of a courageous but difficult and painful emergence into knowledge of sexual difference and the choices associated with it, of the fact that the human and nature are not identical and the challenges that imposes and perhaps of the snake as being a benefactor who introduces the possibility of this momentous shift in consciousness and God as representative of the desire to remain in the bliss of ignorance embodied by pre-reflexive nature –human identification. Perhaps that story could actually be seen as indicating in a symbolic drama our development as a race in terms of our constriction of nature and culture in relation to gender relations and the balance between the human and the natural worlds.

Yvonne: Certainly interesting but you can make this correlation because you are speaking from the perspective of the twenty-first century where a variety of styles of textual and of Biblical interpretation have developed over the centuries. Judeo-Christian thought, prior to the development of such developments in theology as the demythologising of Rudolf Bultmann, interpreted the Biblical narrative as divinely inspired literal account of the Fall as it was called. Also if anyone would prefer to remain in the semi-somnambulist bliss represented by the Garden of Eden rather than the creative conflicts embodied by human life as we know it.

Toyin: Judeo-Christian thought has often constructed the Edenic state as the ideal state to which we hope to return at the end of life, and perhaps, various Utopian conceptions have been influenced by that. They seem to be marked by the notion of ideal being as the absence of conflict, of the clash of mental and emotional gears represented by the often difficult necessity of choice foregrounded by the presence of contrastive choices as the ground for the development of creative complexity in the human relationship to what is given by our biology and the development of the response to this given-ness in terms of social and individual culture.

Yvonne: The snake has had very interesting career in myth. In some mythic forms it is associated with the feminine and some even correlate its sinuous movements with the spiral motif which is correlative with symbolic characterisations of creative change but in terms of the shape assumed by natural forms and the processes through which they undergo change.

Toyin: Perhaps the Hebrews appropriated the snake image from neighbouring cultures whose ideas they despised and rebaptised the snake as an agent of destructive temptation. But they story they constructed suggests possibly, an ambivalence of thought in their characterisation since God is depicted from one perceive as a tyrant who desires to withhold knowledge from his creations, forbidding them to eat of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil and when the snake persuades them to do so, becomes jealous of their knowledge, despairing that “they have become as us knowing good and evil”. Does the narrative suggest that God dreads the acquisition of such fundamental knowledge by his creations? It is this ambivalence, if I can call it that, that enriches and complexifies the narrative transposing it from the realm of a purely transgressive act on the part of a human and suggests a reaching out beyond a limited but blissful state and the snake as a catalytic agent in this rupture in consciousness that ensues. The woman is characterised as the initiator of the human race the temptation the snake holds out.

Yvonne: Thanks. Intriguing. Again, is this possibility of interpretation not possible only from the perspective of twentieth century Western hermeneutics? Could the Biblical writers have been responsive to such complexities or they insinuated themselves into the text without the conscious assent of the writers?

Toyin: It would seem that conceptions of the feminine demonstrate degrees of ambivalence in various cultures, even when the ambivalence emerges in disguised from as we may argue it does in the Biblical narrative. What else is to be expected of negative responses to members of the race who could be demonized but remains the privileged bearer of children? Look at Yoruba traditional thought, for example.

Yvonne: Does it evoke a similar ambivalence?

Toyin: Certainly. In this scheme, women are the primary agents of witchcraft. Their biological prerogatives enable them to wield fearsome powers, but these powers could be wielded for good or evil. At the same time as these constructions are developed and deployed in ways that privilege areas of male supremacy in the bulk of the social space, the creative/destructive power of the female is foregrounded.

Yvonne: This reminds me of the point you made earlier about contrastive possibilities in cultural constructions and interpretation. Are these ideas developed in relation to mythic constructions?

Toyin: Yes. In the Ifa tradition, the central embodiment of traditional Yoruba thought, the witches are often characterised as bloodthirsty creatures and in the rest of the informal constructions in the culture, witches are often understood to be primarily female. The capacities or identity represented by witchcraft are also understood to inhere in their biology. But interestingly enough, aspects of this cultural construction not only conflate destructive and beneficent possibilities of these biologically grounded powers but can also be understood to relate them to terrestrial and cosmic processes of creative growth.

Yvonne: Explain.

Toyin: Convergences emerge between conceptions of the feminine and the constitution of meaning, in cosmic and human terms. The semiotic categories of the Ifa divinatory system, known as the Odu of Ifa, are understood collectively as female and their constitution of forms of meaning as represented by the symbolic patterns of the divinatory system through which the Ifa oracle responds to the queries of its clients is constructed in terms of the procreative capacity of a woman, with the secondary patterns of the divinatory system being understood in terms of the younger children of Odu, their mother.

Yvonne: Interesting. Does this correlation of the hermeneutic forms of the system go beyond these basic symbolic correlations?

Toyin: Certainly. The imagery associated with witchcraft becomes central to Ifa as expressive of the capacity of the oracle to develop a comprehensive grasp of the issues it is asked to deal with. This emerges in the use of the imagery of the bird in Ifa iconography. Birds are associated with witchcraft in the sense that witches are supposed to travel as birds, particularly on missions of deadly intent but the bird becomes evocative of Ifa’s comprehensive vision, a vision that derives from the world of vision from which the witches may also be understood to draw their own powers. And, in relation to Osanyin, the Orisa or deity of the occult powers of plants, they are also expressive of those powers. Herbalogy being an aspect of Ifa.

Yvonne: You did mention that you are developing some ideas of your own in relation to this convergence between symbolism associated with female procreative capacities and cognitive processes as this emerges in the semiotics of Ifa.

Toyin: Yes. I am developing the notion of what I describe as an exchange theory of being which I derive from my study of such correspondences in Ifa hermeneutics in relation to my interests in what I describe as inter-ontological dialogue.. A mode of dialogue between various modes of being.

Yvonne: How does that operate?

Toyin: I develop my ideas in relation to the central iconographic form of Ifa hermeneutics-the Ifa divination tray. The centre of the tray, which, in its emptiness and circular form, could be correlated with ideas of generative space, is the spatial arena where the divinatory instruments represented by the palm nuts or divining beads are thrown in response to the client’s query and the configurations assumed by the divinatory instruments as they are thrown constitutes the oracle’s response to the clients query.

Yvonne: In what sense would you correlate the empty space with ideas of generation apart from the fact that that is the space where the answers to the clients query in terms of the configurations assumed by the divinatory instruments emerges?

Toyin: The conception of the empty space in terms of generative space is amplified by the fact not only is the point at which the oracles response to the specific query of the client emerges, emerging as it does in relation to specific question in relation to a particular issue at a particular point in time and space emerges, but this process of configuring a response to the client’s question operates not simply in terms of the patterns that emerge in relation to this query and the interpretation of the symbolic significance of the pattern that follows but the fact that the entire process which is manifest as what we could described as the level of physical visibility in terms of the geomantic patterns assumed by the divinatory instruments and in terms of verbal expressiveness in terms of the correlation of these patterns with particular verbal expressions through which their symbolic meanings are realised but the fact that these visible operations are understood as representative of the visible level of an invisible process, the second order expression of a first order process which is unseen but is nevertheless determinative of what is subsequently perceived, an expression at ther level of surface structure of a constitution of meaning that takes place at the level of deep structure. This underlying semantic constitution is understood to emerge through the dialogue between the Odu and the Ori or inward spirit of the client. The Odu constitute possibilities of meaning but their meaning value is actuated through dialogue with the clients Ori since the Ori is the repository of the potential of the client and the possibilities implied in/through the manifestation/expression of that potential in the progression of the client’s life.

Yvonne: Interesting. Yes….

Toyin: The construction of meaning is therefore constellated through relationships between various ontological forms represented by the Odu who are understood as conscious entities and the Ori. This cross-ontological constitution ramifies even further in terms of ideas of ontological correlation in relation to the fact that the Odu are understood as semiotic forms that operate as means of describing the spiritual nature as well as of organising the totality of being and its possibilities in terms of semiotic forms represented by the Odu.

Yvonne: So you perceive in the constellation of meaning in the divinatory process a process whereby a cosmological system represented by the Odu operates in a dynamic manner to respond to specific questions in relation to particular issues arising from particular points in space and time from within a repertoire of meaning which operates in relation to cosmographic framework so that the cosmography is brought to play in relation to specific situations

Toyin: Yes. The divinatory process, what Cornelius in reference to astrology, called “the moment of divination” could be understood, therefore, as a constitution in relation to particular space time conditions of the process through which modes of being come into being and the processes they go through as the transmission from one state to another or within one state in relation to various possibilities that come to embody

Yvonne: You are suggesting, then, that the moment of divination, as you call it, is a microcosmic expression of generative processes, understood in terms of a correlation between macrocosmic-as represented by the full range of the cosmographic structure represented by the Odu- and microcosmic processes-as embodied by the focus of this cosmographic structure on /in relation to a particular situation in a specific point in space and time.

Toyin: Exactly. The empty space of the divination tray becomes then a womb of becoming, where macrocosmic process are correlated with the macrocosmic, in relation to particular questions as they emerge in particular points in space and time.

Yvonne: Intriguing construction. Beyond your description of this interpretive possibility, do you intend to use this conception in any way in your work, as an active tool of knowledge?

Toyin: Certainly. I am developing what I describe as cross-ontological thinking. It relates to the notion of developing strategies of thought to explore questions of dialogue, whether understood metaphorically or literarily, between different modes of being. The conception of the Odu as mediating between various modes of being through a semiotically realized cosmography is proving inspiring to my thinking in this regard.

Yvonne: Is that so?

Toyin: Yes. I’m still trying to work this thing out. You did say when we talked the other day that you also trying work out an epistemic strategy in relation to your ideas about feminine biology and consciousness. Tell me about it.

Yvonne: I am developing an argument on a number of fronts. I am working in relation to ideas of embodiment in relation to knowing as well as ideas about how Western thought has developed from the ancient Greeks and propagated via the military culture of ancient Rome.

Toyin: Does is this notion of embodiment in relation to cognitive process gain from a specifically female inspirational base?

Yvonne: I’m still working on that but my argument is for the notion that the act of knowing proceeds along a number of correlative lines, which include the sensory and the mental, that, in fact, the mind could be understood as located all over the body not only in the head since our sensory apparatus operates all over our bodies and are simply routed to their centres in the head.

Toyin: That makes sense. How do you intend to develop that into a cognitive procedure?

Yvonne: That’s the challenge. The central challenge I face here is that the inspirational spring of my ideas derives from the fact that a lot of my ideas emerge from non-ratiocinative sources, of which the forms of bodily knowing are central.

Toyin: Could you please go to the point you were making about the military origin of modern Western discursive forms?

Yvonne: I was referring to its argumentative structure. Why must a question be examined, a point established, through the marshalling up of squads of points in favour of that point, arrayed in opposition to contrastive ideas? Why must the development of ideas and the examination of issues always resemble a conflict between combatants, the opposing side being the ideas not certified by the writer and the other side represented by the ideas they credit. Or even if this position does not emerge from the beginning, it emerges as the text progresses, so that there always exists or is developed a structure of opposition, between two groups of ideas.

Toyin: But is that not to be taken for granted if the development of a perspective on a topic? Does one not need to examine contrastive ideas and arrive at those that are more valid? All ideas cannot be equally valid.

Yvonne: Noted. But I am not pleading for an uncritical embrace of all ideas available in relation to a question. All I am suggesting d that I seem to observe in the fundamental structure of investigation in scholarship the notion of a Manichean/oppositional duality, in which either/or propositions determine the structure of thought.

Toyin: You think such dualities are inadequate for knowledge?

Yvonne: Yes. Because reality is often multiplex, kaleidoscopic, even fragmentary. To what degree can we isolate one phenomenon from another? Don’t many phenomena, particularly those relating to issues of value, infiltrate each other? I find myself using a military metaphor here, but I think you get my point.

Toyin: Can you suggest a style of investigation that would take advantage of the interdependence you are describing?

Yvonne: I am still developing it. I am thinking of something like a navigational form of thought, where the purpose is to navigate our way in relation to as broad a range as possible of the possibilities of perception in relation to a subject. I am thinking of Deleuzian models of reasoning, and of autoethnographic analytical methodologies…Rosi Braidotti refigured Deluzian ‘platforms’ in service of feminist values and approaches, calling such perspectives ‘nomadic’ or ‘migrating.’ The crux was that, as with the platforms of Deleuze, ideas could be examined from various perspectives in turn, resulting, in their sum, in a democratic perception of the issue ‘in the round.’ No one point of view would be privileged; all multipersectival views would be received as different, sightings along different lines, but equal.

Toyin: I seem to recall descriptions of essays by the French writer Michel de Montainge along those lines.

Yvonne: Perhaps. But such styles of thought have not gained centrality in Western academe. The ethos of the warrior, who is certainly marshalling opposing forces against each other and of the hunter who operates in terms of an adversarial relationship with the Other represented by the animals he preys on, dominates scholarship, where this is conducted in terms of opposition between ideas and discourse is more often than not argumentative, with the qualities of mental combat embodying martial values.

Toyin: Intriguing. How do you arrive at conclusions? Do you stumble upon them or do you defer them endlessly?

Yvonne: I know you are making fun of me but even those suggestions might not be as ridiculous as they sound.

Toyin: So, do we swim forever in a soup of inconclusion or do we arrive at any shore as we navigate the possibilities of an idea or subject?

Yvonne: Certainly. To postulate a permanent nondecision, nonjudgement would be irresponsible. That would be an excess of relativistic thinking. I am suggesting, as I still develop these ideas, a movement towards resolution with a tacit understanding that every resolution demonstrates some degree of the provisional and the specificity with which we circumscribe perspectives facilitates a bracketing out of ancillary but relevant aspects of those perspectives which we have relegated either to the background or to non-existence in our cognitive worlds.

Toyin: This reminds of a way you described this idea the other day-as a style of thinking the mobility of which dramatises a deferral of judgement in the name of a cognitive “synaesthesia” that enables/facilitates a perception of the subject matter from a variety of perspectives, even contradictory perspectives….

Yvonne: Yes…leading to the possibility of convergence, or, even if not of convergence, of mutual tension, in which the absence of an ultimate coherence is itself an understanding that suggests possibilities of holding possibilities, understandings in a creative tension….

Toyin: You think, then, that such a tentative style of interpreting phenomena might be more in harmony with the paradoxical realities of existence than the notion of certainty, of linear coherence, even of dialectical balance that is /currently privileged in conceptions of the effort to arrive at meaning….

Yvonne: My thinking is moving in that direction.

Toyin: You would seem, then, to be thinking in terms of an understanding of the search for knowledge more in terms of a quest for meaning, for structures, patterns, processes of understanding through which can be enriched, even if the ultimate truth value of the understanding arrived at, of the processes developed, may not be fully ascertained, are understood as to a degree, in flux

Yvonne: But then, this does not imply, however, an absolute relativity. Absolute relativity, endless cognitive flux, could be more productive of a destructive anarchy, a breakdown in standpoints of collective responsibility than a liberating prospect

Toyin: How do you hope to escape from an absolute relativistic position?

Yvonne: By treating conclusions, where necessary, as tentative in the ongoing project represented by the exploration realized through cognitive navigation. The sensitivity to the plural possibilities inherent a phenomenon or an issue or idea highlights the tension between the quest to know, to push back and even reshape boundaries that necessarily characterise a rethinking of our cognitive horizon, our epistemic envelopes, in contrast to the need to conserve, consolidate and apply what we gain in the process in contrast with, in tension with the renewed impetus to continue that quest, which continues beyond the bounds of what we can perceive at any point in time, as Dion Fortune puts it, may even take us out of space and time, “beyond the skyline, where the strange roads go down”.

Toyin: You mention Fortune. That is intriguing. How does she come here and how did you start on the development of these ideas?

Yvonne: It began in relation to my experience of ways of knowing that could not be accounted for by prevailing paradigms. And by my efforts as a woman, to find new ways of thinking that would transcend or even avoid the limitations of the patriarchal thinking that I have often come across. Feminist thinkers often recognise such patriarchal thinking but do not often realise its origin in martial structures and even use the same critical tools while debunking its fruits. I want to go to the very source, to the very girders that hold it up, to the underlying skeleton, as it were, of this style of thinking.

Toyin: Please elaborate.

Yvonne: I realised that I could know things through my skin, and not simply by touch. I could intuit people’s mental sates without talking to them. How could I explore such forms of knowledge without descending to superstitious thinking and demands for acceptance for my claims without empirical proof? I realised that the key would be to examine the question of ways of knowing and develop an approach from that point that would be inclusive of my own experience.

Toyin: And your encounter with patriarchal thinking?

Yvonne: I kept coming up against both circumscriptions of reality that were demeaning of both women and the men and women who perpetuated them as well as accounts of alternative styles of thinking.

Toyin: Amazing how our experiences correlate. I was also challenged by my experience of unusual ways of knowing. That is what has led me into investigating traditional Yoruba and Benin thought for both explanatory models and ways of developing this cognitive mode further.

Yvonne: Could you explain?

Toyin: Under the influence of the English Hermetic thinker and occultist Dion Fortune explored the notion that there exist various forms of mind and not resent the individual mind. One could speak of the combined influence generated by the mental orientation of a group over along period of time. One could also speak of the mind of nature. She claimed that both conceptions of mind are vital to a recovery of the vitality of religious cultures where these have been disrupted, distorted or even erased by persecution, as in the case of pre-Christian thought in Britain. I realised the parallel with Africa which has suffered similar efforts at re-inscription by Christianity and I went to wok to apply these ideas to the Ifa divinatory system developed by the Yoruba of Nigeria and to nature spirituality in Benin, in relation to similar practices in other parts of Nigeria.

Yvonne: Then what happened?

Toyin: My experiences raised questions of interfaces between forms of being, between human consciousness and the ideas with which human beings work, between human beings and natural forms.

Yvonne: What were these experiences?

Toyin: Experiences that suggested a participation in the community constituted by the Ifa tradition understood as uncircumscribed by space or perhaps time, the manifestation of a sense of presence that began to emerge when I thought about my plans of developing Ifa in terms of a system of literary criticism, the sudden emergence of an insight into the possibility of realizing this that emerged when I was working on an entirely different subject- South Afro can anti-apartheid poetry, and the persistence of such experiences in relation to my efforts in developing the cognitive potential of the system in terns that could be appreciated in relation to contemporary thought.

Yvonne: What did all these suggest to you?

Toyin: I began to ask myself what the sources of my inspirations were. Did it justify Fortune’s notion that groups constituted a group mind, the energies of which could be reached by others outside the group? Or my Ifa teacher’s idea that the Ifa system was empowered by the Odu, which are both categories of organisation similar to chapters of a text, in this case an oral text, as well as sentient entities and that their nature as nonhuman forms which the human being could reach implied that they are adaptable to various cultural and linguistic backgrounds?

Yvonne: Where does the nature spirituality stuff come in?

Toyin: That was particularly striking and relates again to the question of cultural appropriation by people who are not, racially or by previous empathic affiliation, part of that culture. I spent time exploring Fortune’s ideas about the mind of nature by contemplating trees, spending time in contemplative silence in woodland and forest.

Yvonne: Did that have any effect on you?

Toyin: Yes. Gradually, I began to observe a difference between various kinds of tees that was not reducible to a purely material difference, to differences in purely material biology.

Yvonne: Non-material biology then?

Toyin: Perhaps one can put it that way. I began to observe that the sacred trees in Benin City where I lived, the trees used for ritual, seemed to have an aura, an immaterial field around them which I also saw on some trees in the woodland and forest. Most of them were either trees accorded special status in the traditional religion even though they were not actively used in religious or other similar purposes and others which might not have been seen as having any religious value but still demonstrated that sense of an unusual aura. What I found particularly striking was that my intuitive vision was confirmed by people in the localities where I sighted these trees. I could literally tell a tree that had a sacred function in a locality simply by looking at it. I did not have to have been thee before or known anything about the specific tree or of its species. I could tell that identity by observing what seemed to me like an aura around it.

Yvonne: So, it would seem, then, that you shared an intersubjective space with the people who identified those tress as sacred, even though you did not have access to their cultural constructions

Toyin: That suggested to me that those cultural constructions were the development of biological properties in both the human being and nature.

Yvonne: Meaning?

Toyin: That these trees and groves could be understood as possessing a quality that I could perceive on account of a sensitivity cultivated through contemplating such trees and others different from them repeatedly so that a sense of difference between them was gradually established for me.

Yvonne: But, could you really say that you hardly had access to their cultural constructions? Had you not read books about similar aspects of African culture and read accounts of similar conceptions from other cultures?

Toyin : That’s true. I had read about African cultures along those lines. But I had not thought about my reading in Romantic and Symbolist thought along those lines.

Yvonne: You could speak of sharing in a culture that was realized in particular cultural developments, in various geographical, spatial frameworks but a similarity of culture, nevertheless.

Toyin: Hmm…questions about cross-cultural transmission again emerge here. Following this trend of thought to its logical conclusion would imply that one could gain access to significant identification with a culture, through observing parallels between the target culture and other cultures and trying to embody what one has learnt in one’s own life.

Yvonne: I would think so.

Toyin: Fortune makes a similar point about lighting your own dormant fire with fire from someone else’s hearth. Could biology be understood to play any role here, then? My notion that I was developing an latent capacity for sensitivity to biological properties of nature?

Yvonne: I doubt if nature and culture, biology and human interpretations are so distinct. To what degree can we speak of the discontinuities between them? Perhaps we could speak of cultural propensities facilitating the sensitivity to biologically endogenous qualities? But how does this relate to Ifa, to interpretations of the female body in relation to witchcraft, which was what we started our discussion with?

Toyin: This zone of communication between different modes of being is understood in Yoruba and Bini traditions as the prerogative of Ifa and of witches. Ebohon, a Bini priest, describes some trees as witches, his ideas being expressive of a culture where humans are understood to be able to cultivate the ability to communicate with plants. The Ifa system is organised in terms of possibilities of dialogue between different modes of being and Ifa’s younger brother, as he is called, Osanying, the Orisha of herbalogy, since Ifa priests are also at times herbalists, represents the world of human relationship with plants. The sense of encounters with non-embodied presences, related to my studies of Ifa where I adapted techniques derived from Western hermetic ceremonial magic, Eastern and western meditation techniques and the related experiences of inspiration also suggest correlations with ideas of transmission of ideas in terms of encounters, however these are understood, between various forms of being, whatever the ontological status we ascribe to the mythic forms with which I tried to relate and to the sense of non-embodied presence often associated with my experience of Ifa.

Yvonne: So it would seem, then, that we are both intrigued by experiences of and ideas relating to forms of knowing that are not ratiocinative and are not rational in the conventional sense.

Toyin: And which relate to relationships between embodiment in relation to knowledge and reflection in relation to knowing

Yvonne: And to questions of the interface between the cultural and biological along these lines

Toyin: Interesting that we have both come upon the image of the witch in relation to such ideas.

Yvonne: The witch as an embodiment of the reviling of women in pre-Renaissance Europe and of valorisation of the feminine in modern Western feminist spirituality.

Toyin: In Yoruba thought as the nexus for positive and negative conceptions of the feminine

Yvonne: And in both cultures, the witch as embodying conceptions of physicality, occult power and choice, whether negatively, as in pre-modern Western conceptions, or positively, as in more contemporary understandings—or ambivalently, as in traditional Yoruba thought.

Primary Sources

Kramer, Henricus (Institoris) and Sprenger, Jacobus (2006). Malleus Maleficarum, Ed. and Trans. Christopher S. Mackay, 2 vols. Cambridge University Press. (2009) The Hammer of Witches: A Complete Translation of the Malleus Maleficarum, ed. and trans. Christopher S. Mackay. Cambridge University Press.

Pliny (1942), Natural History. Ed. H. Rackham. Cambridge University Press. dei Segni, Lothario (Pope Innocent III) (1978). De miseria condicionis humane. Ed. R. E. Lewis. Athens.

Secondary Sources

Adepoju, Oluwatoyin (‘Toyin) Vincent and Owens Yvonne (Forthcoming in 2021). The Cave of Becoming: A Discourse on Feminine Physiology and its Epistemic Possibilities in the Yoruba and Wiccan Correlations of Feminine and Spiritual Power. In Trans-Disciplinary Migrations: Science, the Sacred, and the Arts, Adepoju, Oluwatoyin (‘Toyin) Vincent and Owens Yvonne Eds. Cambridge Scholars Publishers.

Abimbola, Wande (1976). An Exposition of Ifa Literary Corpus. Oxford University Press.

Afolayan, F. (2006). Oyeronke Olajubu. Women in the Yoruba Religious Sphere. Albany. African Studies Review, 49(3): 179-181.

Beier, Ulli (1975). The Return of the Gods: The Sacred Art of Susanne Wenger. Cambridge University Press,

Behringer, Wolfgang (2004). Witches and Witch-Hunts: A Global History. Cambridge University Press.

Bickel, Barbara (2005). Embracing the arational through art ritual and the body. Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Imagination and Education. Imagination Education Research Group. Simon Fraser University.

Bitel, L. M. (2002). Women in Early Medieval Europe: 400—100. Cambridge University Press.

Blamires, A., with Pratt, K., and Marks, C. W., eds. (1992). Woman Defamed and Woman Defended: An Anthology of Medieval Texts. Oxford University Press.

Braidotti, Rosi (1994). Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory. Columbia University Press.

Brauner, Sigrid (1995). Fearless Wives and Frightened Shrews: The Construction of the Witch in Early Modern Germany. University of Massachusetts Press.

Douglas, M. (2003). Purity and danger: An analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. Routledge.

Gimbutas, Marija (1991). The civilization of the goddess, J. Marler, Ed. Harper. (1989). The language of the goddess. Harper & Row.

Keyes, Ken (1984). The Hundredth Monkey. Los Angeles: DeVorss & Company.

McCorriston, J., Harrower, M., Martin, L., & Oches, E. (2012). Cattle cults of the Arabian Neolithic and early territorial societies. American Anthropologist, 114(1): 45-63.

Green, Marion (1991). A Witch Alone: Thirteen Moons to Master Natural Magic. Harper Collins.

Hallen, B., & Sodipo, J. O. (1997). Knowledge, belief, and witchcraft: analytic experiments in African philosophy. Stanford University Press.

Lautman, F. (1993). Houdard (Sophie): The Sciences of the Devil. Four speeches on witchcraft (15th-17th centuries). Archives of Social Sciences of Religions, 84 (1): 319-319.

Kord, S. (2007). From Evil Eye to Poetic Eye: Witch Beliefs and Physiognomy in the Age of Enlightenment. In Practicing Progress. Brill Rodopi: 35-57.

Kuhrt, A. (2001). Women and War. NIN: Journal of Gender Studies in Antiquity. Brill Academic Publishers, Volume 2, Number 1. July, 2001.

LaGamma, A., & Pemberton, J. (2000). Art and oracle: African art and rituals of divination. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Lawal, B. (1996). The Gẹ̀lẹ̀dé spectacle: art, gender, and social harmony in an African culture. University of Washington Press.

Lincoln, B. (1981). Priests, warriors, and cattle: a study in the ecology of religions (Vol. 10). Univ of California Press.

Lovelock, J., & Lovelock, J. E. (2000). Gaia: A new look at life on earth. Oxford Paperbacks.

Matsumoto-Oda, A., Hamai, M., Hayaki, H., Hosaka, K., Hunt, K. D., Kasuya, E., … & Takahata, Y. (2007). Estrus cycle asynchrony in wild female chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 61(5): 661-668.

Matsumoto-Oda, A. (1999). Female choice in the opportunistic mating of wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) at Mahale. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 46(4): 258-266.

McCracken, P. (2010). The curse of Eve, the wound of the hero: blood, gender, and medieval literature. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Owens, Yvonne (2019). The Hags, Harridans, Viragos and Crones of Hans Baldung Grien. Hans Baldung Grien: New perspectives on his work. Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe: 194-203.

(2017). Pollution and Desire in Hans Baldung Grien: The Abject, Erotic Spell of the Witch and Dragon. Images of Sex and Desire in Renaissance Art and Modern Historiography. Routledge: 174-200.

(1999). Barbara Bickel’s Sacred Wounding: Woman’s Body as Original Temple. Artichoke Journal: Writings About the Visual Arts, Fall/Winter 1999: 38—42. https://www.academia.edu/20847868/BARBARA_BICKELS_THE_SPIRITUALITY_OF_EROTICISM_A_COLLABORATIVE_ART_EXHIBITION_AND_PERFORMANCE

Purkiss, D. (2013). The witch in history: early modern and twentieth-century representations. Routledge.

Ranke-Heinemann, U. (1990). Eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven: Women, sexuality, and the Catholic Church. New York: Doubleday.

Redgrove, P., & Shuttle, P. (1978). The wise wound: menstruation and everywoman. Penguin Books.

Stephens, W. (2003). Demon lovers: Witchcraft, sex, and the crisis of belief. University of Chicago Press.

Williams, G. S. (1999). Defining dominion: The discourses of magic and witchcraft in early modern France and Germany. University of Michigan Press.

De Waal, F. B. (2005). Morality and the social instincts: Continuity with the other primates. Tanner lectures on human values, 25, 1.

Oluwatoyin Vincent Adepoju is an Independent Scholar working at the intersection of the visual and verbal arts, philosophy, spirituality and science.

Oluwatoyin Vincent Adepoju is an Independent Scholar working at the intersection of the visual and verbal arts, philosophy, spirituality and science.

He is self educated in his various fields of interest except literature where has a BA and two MA degrees.

Yvonne Owens is a past Research Fellow at the University College of London, and Professor of Art History and Critical Studies at the Victoria College of Art, Victoria, BC. She was awarded a Marie Curie Ph.D. Fellowship in 2005 for her interdisciplinary dissertation on Renaissance portrayals of women in art and sixteenth-century Witch Hunt discourses. She holds an Honors B.A. with Distinctions in History of Art from the University of Victoria, British Columbia, a Master of Art with Distinction in Medieval Studies (with an art history thesis) from The Centre For Medieval Studies at the University of York, U.K., a Master of Philosophy in History of Art from University College London and also a Ph.D. from UCL, also in art history. Her publications to date have mainly focused on representations of women and the gendering of evil “defect” in classical humanist discourses, cross-referencing these figures to historical art, natural philosophy, medicine and literature. She also writes art and cultural criticism, exploring contemporary post-humanist discourses in art, literature and new media.

Yvonne Owens is a past Research Fellow at the University College of London, and Professor of Art History and Critical Studies at the Victoria College of Art, Victoria, BC. She was awarded a Marie Curie Ph.D. Fellowship in 2005 for her interdisciplinary dissertation on Renaissance portrayals of women in art and sixteenth-century Witch Hunt discourses. She holds an Honors B.A. with Distinctions in History of Art from the University of Victoria, British Columbia, a Master of Art with Distinction in Medieval Studies (with an art history thesis) from The Centre For Medieval Studies at the University of York, U.K., a Master of Philosophy in History of Art from University College London and also a Ph.D. from UCL, also in art history. Her publications to date have mainly focused on representations of women and the gendering of evil “defect” in classical humanist discourses, cross-referencing these figures to historical art, natural philosophy, medicine and literature. She also writes art and cultural criticism, exploring contemporary post-humanist discourses in art, literature and new media.