Happiness as a Subversive Activity

An Interview with Ivan Szendro on Commedia Dell’Arte as Healing & Resistance in Communist Hungary

by Ronald L. Boyer

Sonoma State University

In the last issue of Coreopsis (Vol 3 No. 1 Fall/Winter 2013/14), Hungarian myth-carrier and shaman, Ivan Szendro, discusses his transformation from a “player-on-stages” into a “player-in-a-myth”, a transformation catalyzed by his encounter with the Hungarian myth, the Judge of Blood, a myth in which Ivan found, to paraphrase C. G. Jung, the “myth that he was living”. The Judge of Blood is a living collective myth passed down through countless generations to Hungarian villagers living near northern Transylvania, tiny remote communities in the countryside of Hungary where vestiges of myth and folklore were inherited from shamanic traditions derived originally from Siberia. The trouble with the Judge of Blood, Ivan soon discovered, is that it had become a myth without a hero. In a time lacking in collective hope, the Judge of Blood—the legend of the tyrant Hayno—was an apt metaphor for the historical conditions of Hungary itself under Communist dictatorship. But in his personal development, Ivan had already matured beyond the merely hopeless vision of the future the myth embodied. A healing vision, a story filled with collective hope and meaning, was also required. Ivan’s evolving new role was to restore a hero—and the power of renewed hope that invariably accompanies such acts—both to the myth itself and, through his creative retelling and reinterpretation of the myth, to his fellow countrymen and women. This inspired work of vision, healing and renewal—a sacred function common to shamanism and myths the world over—began with Ivan’s more than 500 creative performances of the myth as a narrative of hope and renewal that he continues to embody both in his individual healing work with clients and as a leader in ongoing collective efforts to heal and restore the culture of those remote Hungarian communities where he received his calling.

This interview continues Ivan’s story as a “prequel” focusing on the early years of his transformation, when he was still a performing artist in the process of becoming—unconsciously at the time—the myth-carrier shaman he is today. As a young actor fresh out of the theatrical academy in a nation suffering under the yoke of Iron Curtain despotism in the 1970s, Ivan—like many of his peers in the creative community and the populace in general—struggled with the widespread apathy and despair that gripped Hungary under Soviet Communist dictatorship. This challenging socio-political environment in the polis of Communist Hungary served as Muse to Ivan and many of his artistic contemporaries, giving rise to a “soft” resistance, an Eastern European version of America’s Hippie “flower-power” movement. In Ivan’s case, this took the artistic form of the wandering improvisational troupe Tanyaszinhaz (Hamlet Theatre),[i] in the European theatrical tradition of Commedia Dell’Arte.[ii] Their purpose was less an intentional provocation of their Communist masters than a creative rebellion against their own all-too-frequent apathy and suicidal despair. It was a gesture of self-healing, for the actors themselves and for their audiences—an artistic revolt that took the shape of farce, performed as improvisational folk and street theatre. Their message was simple: Even in the darkest times, we can still smile. We can laugh. The sun is still there for us all. In his reminiscences of life as a wandering artist and performer, we glimpse the seeds of transformation that were already growing Ivan in the direction of his new calling as a self-healing harbinger of hope and renewal.—Ronald L. Boyer

RON BOYER: Tell us about the situation in Hungary that gave birth to your populist resistance in the form of comedic performance art and street theatre. What can you tell us about the socio-political context in Hungary at the time?

IVAN SZENDRO: Hungary in the early 1970s was under tremendous pressure to accommodate Soviet demands after the brutal suppression of the failed 1956 Revolution. At that same time, the regime was trying to give a feeling to our Country that we were “the happiest barracks in the socialist block.” And compared to countries like Poland, E. Germany, and others, this was true.

There were some very weak liberal breezes blowing in Hungary at the time, but mostly we created street theatre in order not to feel totally stifled. This was a dictatorship in full power. And our Country dared not forget the terror and retaliations that followed in the wake of the events of 1956. In the theatre, we tried to talk about what was truly happening but cloaked in metaphors to disguise our intentions. But the government censors were sufficiently educated to recognize the hidden messages and stopped them.

All we needed was a back curtain, four or five actors, a musician, sunshine, and laughter to feel free from dictators. Here we perform an opening scene in Kiskunhalas, Hungary. Photo by Andras Straszer, 1972.

RB: Who formed the acting company and what was the inspiration for that?

IS: The inspiration for the wandering theatre began when I was a new actor in the Szeged National Theatre, the second largest national theatre after Budapest. The Hungarian mentality, under long-suffering history and collective bad memories, tended to be very pessimistic at that time. This pessimism was even more acute, more visible in the artistic world. The main avenues of escape from our social conditions were widespread alcoholism and a frighteningly large number of suicides. My first reaction upon graduating from the Theatre Academy gave rise to a series of rebellious acts like cleaning up the pigeon shit in front of the National Theatre, the audience could go in with clean shoes and forcing the building maintenance manager to stop drying his family’s laundry on the stuccoes of the theatre. I also refused to perform on official Communist holidays, foregoing a common strategy for Hungarian actors to green-light their careers. These were the modest forms of my rebellion. And the authorities started to pay attention to these and similar misbehaviors on my part.

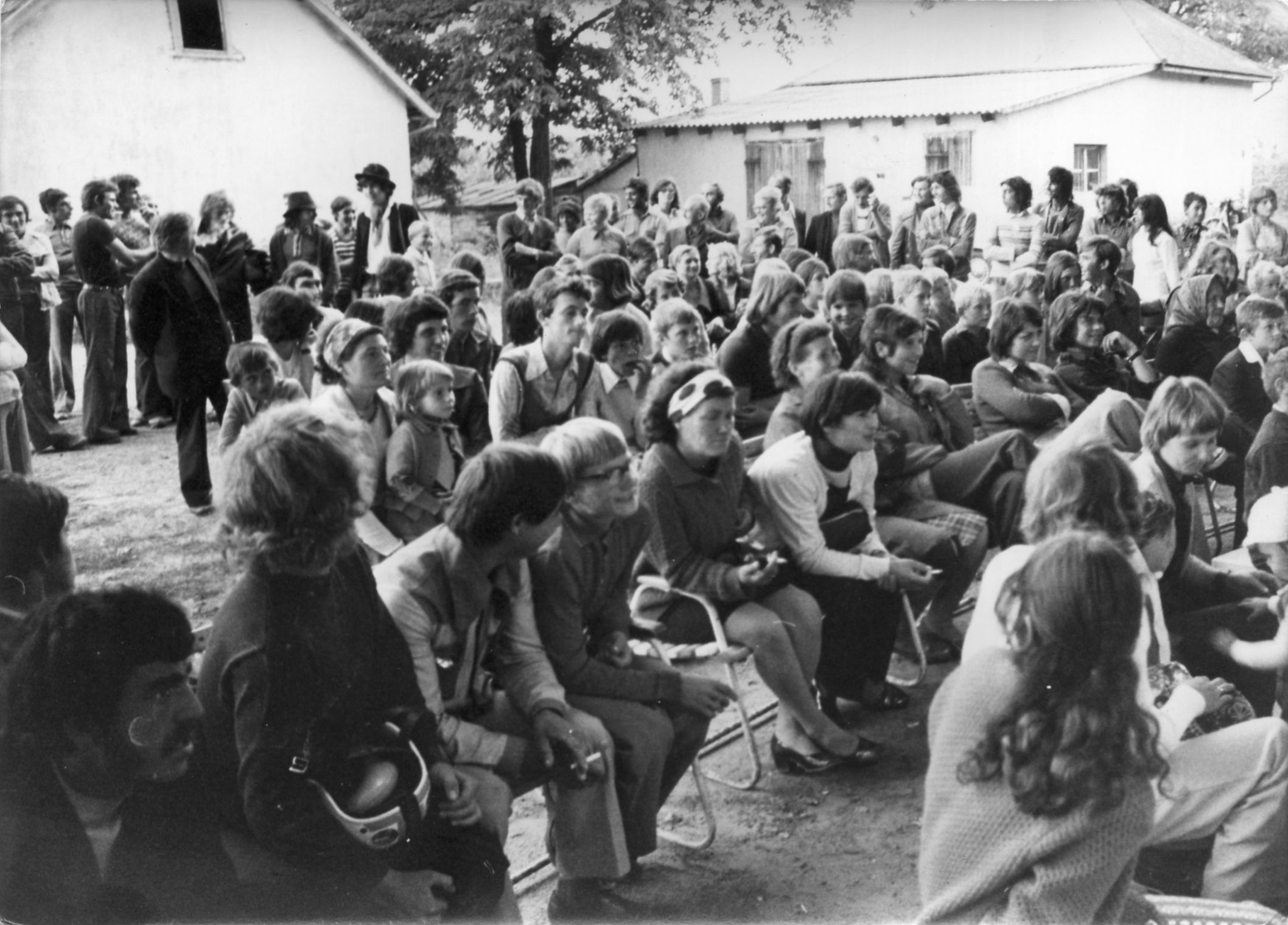

These hamlet residents gathered in the schoolyard to see us perform. It was probably the first time they had seen a theatrical production. Performance of The Charlatan, Kistelek, Hungary. Photo by Andras Straszer, 1972.

Yet my major enemy wasn’t the dictatorship but rather my own ego. I was searching to liberate myself from myself, if that makes sense. I was striving to be free in my expressions, to liberate that limitless inner talent that we all possess. I started taking long walks, venturing out into the countryside to small hamlets on the outskirts of the City, where people lived in a more primitive, traditional manner—without electricity. And without having ever experienced theatre in their entire lives I began conspiring with small culture house directors, local teachers, and others who directed the cultural lives of their small communities, to bring some shows out to the villagers. That was my first step, which in the long run opened into my journey along the shamanic path. The clearest manifestation of this change in me was that I didn’t accept credit for the founding or organization of the whole venture. In this way I put pressure on young colleagues who sympathized with the idea but whose conformist reflexes dictated just being “an actor.” I wanted to share the responsibility with them. I wanted them to become more than just actors: writers, organizers, negotiators, stage builders, etc.

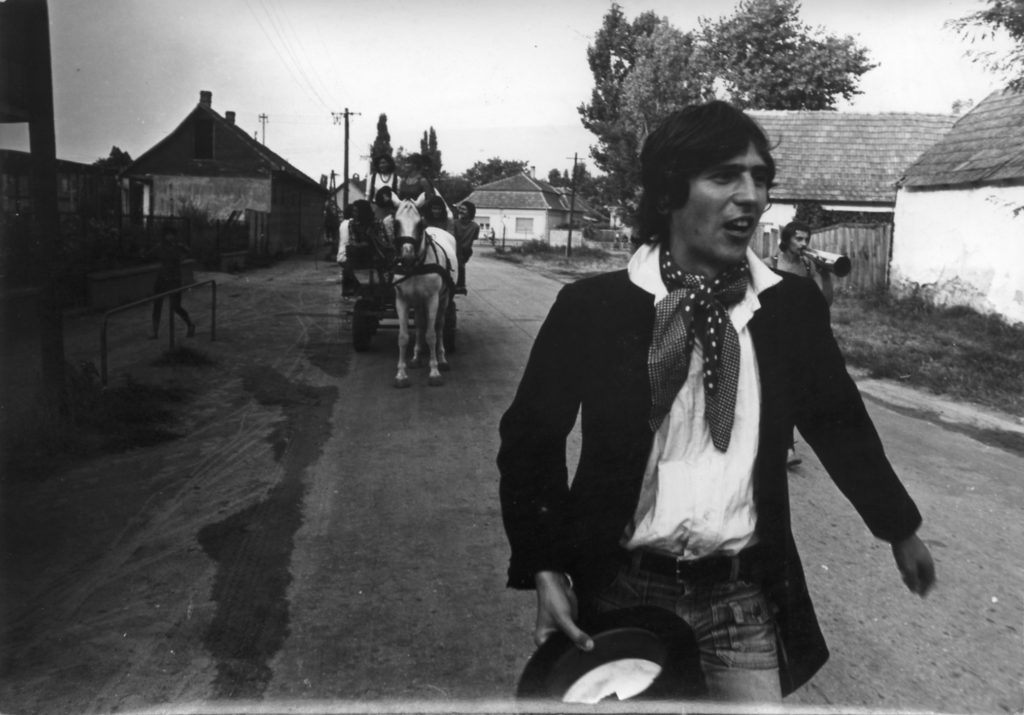

Announcing a show as we proceed through the village streets of Kiskoros, Hungary. The members of the troupe are behind me riding in a rented horse cart. Being loud and cheerful was essential! Photo by Andras Straszer, 1972.

The Commedia Dell’Arte proved a good framework for these popular folk theatre shows, because the written text was a small part of the performances. The larger part was creative improvisation. So the afternoon in a new village was always a good time to collect rumors we could use as additional material built into our performances, like gossip about the local “army Major and his new mistress” or other hidden secrets of the village we could use for comedic material.

RB: Could you share a brief history of the troupe and its evolution over time?

IS: At first, some very prominent, successful colleagues came along with me. But eventually they were too busy to continue. So I started to cultivate undiscovered new talents at our theatre, who were motivated and hungry to go on stage, willing to make more effort than just to act. But even with them, I once had to go on a two day hunger strike, because they were reluctant to build a stage. And we were also joined by a lovely and talented young man, Sandorka, a midget who became a mainstay of our troupe. I first met him at a bus station near a factory in the suburbs where he entertained his fellow workers after work. He joined us and delighted many audiences in our performances.

The rehearsals were idyllic and took place in a vacation home belonging to one of the actors’ parents, at Lake Balaton. But the first show was a shock for them, having never played outside the walls of official theatres. Here they were, having to go into the streets, shouting and calling the audience to the show. On the first morning before the matinee, three of our female colleagues didn’t even show up! I couldn’t believe it. I went to their room, where I found them all hiding in bed, dressed up in their performance outfits, trembling and afraid to leave their room to meet the audience. Improvisation is something you can imagine but you can’t learn apart from direct experience. You need to actually meet the loud naïve audience, as ours was, to respond to the spontaneous reactions, to participate in the collective jokes or even to tackle the Village Fool who jumps on stage uninvited. Or in the middle of the story to shower the prima donna with an enormous bunch of flowers, or deal with some brawler who wants to prove that he is better at imitating a limp than you are.

RB: Can you describe more about what the plays themselves were like?

IS: The plays themselves consisted of a series of three or four short farces, each ten minutes long. The plays originally might have been created by a major playwright like Rabelais or Villon, or by anonymous actors patching material together from various sources. This process would start earlier at a village inn, where we typically collected local material in the afternoons before the play. Then we would rent a horse-drawn carriage and with trumpet and drum go about the village announcing the play. Most of the time just the sick were staying home, but even they came out to see us. There were some basic farce stories like The Lame and the Blind, portraying how they would fight and compete with each other until they established the first “Beggar Labor Union.” There were lots of ways for us to pretend to fall off the stage into the crowd, making them laugh and getting small donations from the audience. And we had the character of the Two Faced Comedian who tries to keep the store running while the absent owners, a man and a woman, went off to get drunk together.

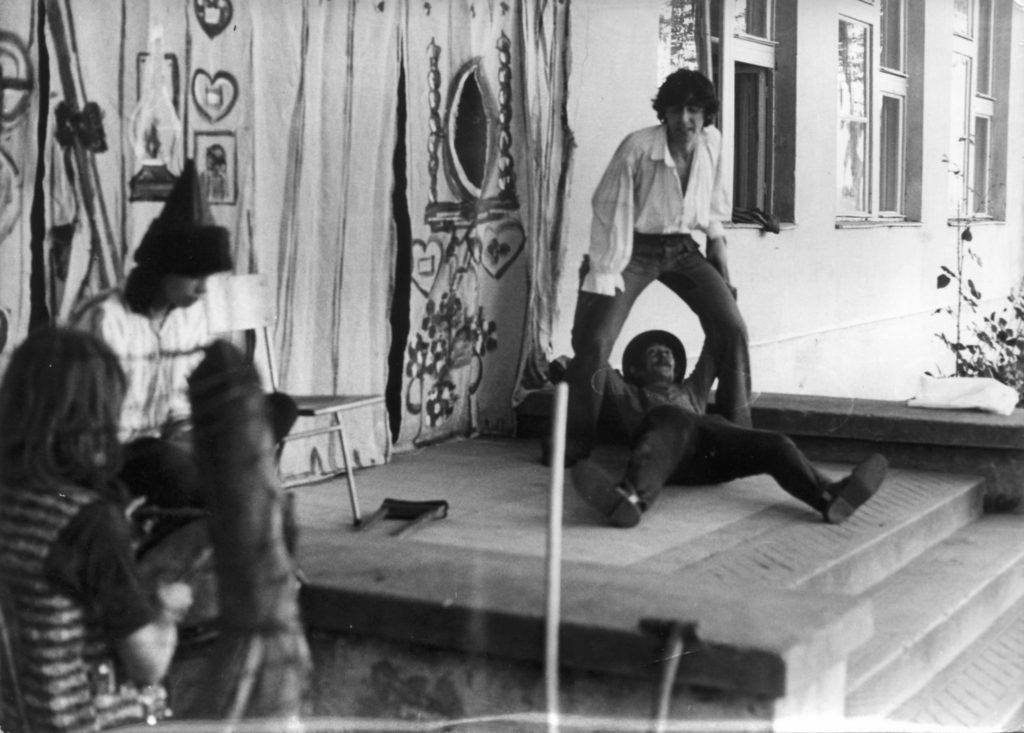

We never let the stage come between us and our audience. Performance of The Blind and the Lame, Kecskemet, Hungary. Photo by Andras Straszer, 1972.

RB: Many artists resisted the occupation by both fascist and communist totalitarian regimes in Europe during the past century. Albert Camus resisted the Nazis, speaking truth to power in disguised shapes, for instance, creating The Plague as a metaphorical novelistic critique of the Occupation. Did you consciously identify with this intellectual and moral obligation of the artist in our time, as Camus asserts, to speak truth to power?

IS: My father and mother actively participated in the resistance against the Nazis, and I learned from their lives after the war, how a beautiful idea—in this case Communism—can turn into an actual horror. So my search was for a more spiritual way of life. My daily reading was on Taoism, like the Tao Te Ching by the Chinese sage Lao Tzu. But even this caused trouble with the authorities, because speaking among ourselves about the “Tao,” the secret police misheard “Mao.” And in Hungary in the 1970s, Chairman Mao’s anti-Soviet message was much more dangerous than the ancient Chinese philosophy. It was very difficult for me to explain the difference to the investigator at the local police station!

The point is that I was trying to create inner peace, a sane refuge in an otherwise crazy world. We were not trying to provoke the dictatorship. That’s why it’s interesting that even with this non-threatening, sunny message, the officials were very suspicious. The reason was probably that the performance wasn’t initiated from above, by the official Cultural Ministry, and they didn’t like that. I think the most irritating part for the officials was, at the same time, the most appealing aspect of our plays for the audience: our smiles, our happiness.

RB: How did political danger manifest typically? What risks did you take as a group?

IS: The main risk was that our careers as actors could be ruined. We could be placed on a secret “black list,” indicating that we were against the regime. To be honest, even at that time there were so many officials in the lower as well as higher levels of the cultural administration who secretly sympathized with us, even those who in words distanced themselves but in fact supported us financially. So I don’t consider this a heroic act, like my father who had risked his life by directing a show against the Nazis just two weeks before Hitler occupied Hungary in 1944.

Sometimes the porch of a school was enough for a stage. Performance of The Blind and the Lame, Kistelek, Hungary. Photo by Andras Straszer, 1972.

It’s also important to note that the risk arose naturally. We didn’t invite or provoke it. Political scandals weren’t reported in the papers. They were always covered up, so you heard them just as personal and local stories, often as rumors. These stories formed the substance of our performances. Our tricks were sometimes obvious, and the “censor-sponsors” might ask me to leave this or that out. I would promise never to repeat the same stuff. But the officials still tried to divide us. They would ask: “Is the leader, Ivan? Or is it Arpad? Is it Balazs?” But we didn’t take their bait. So they tried to find ideological hooks in our group, religious figures or politically dangerous people. But our message was different than they expected. We weren’t overtly political. Our message was simple: That in a dark age you can still smile. You can still laugh. The sun is still there for us all.

The real political trouble came in the third summer when we decided to stage a classic passion play, The Three Christian Maidens. It was written during the Middle Ages to protest the Turkish Occupation. In the play, three girls resist pressure from a tyrant, the Turkish Emperor, who is forcing them to become Turkish and join his harem. It’s hard to imagine from this vantage point how it was that everyone understood that it was also a veiled protest against the Russian Occupation. But it obviously struck that chord with the authorities.

RB: How did the message of these performances provide social critique of the tyranny and support the people in resistance?

IS: These shows didn’t intend to stir resistance or motivate the people to rise up against the Hungarian government, or against the Russians, but to stir the actors themselves—and their audience across the land—to rise up from the mass apathy and despair that was our true enemy.

Two years later, when I was already working on my personal myth, this changed when I traveled all over Hungary—then to Holland, France, and later the United States—sharing the ancient Hungarian legend of the Judge of Blood. This legend, with very old roots in our culture, was also a metaphor for the dictatorship. So that was a clear message against the “Grinding Machine” Dictator, as we called him. But by then I was a myth-teller instead of an actor or mere theatrical artist, working apart from mainstream official society. I felt much closer to the burgeoning avant-garde art world by then, and I was close to recognizing my calling as a shaman. I told the legend more than 500 times, until the French newspaper Liberation wrote an article about my show. Then the Hungarian authorities had enough. They took my passport and interrogated me. But that’s another story.

[i] The name of the troupe, Tanyaszinhaz, or Hamlet Theatre, refers to the location of the folk theatre performances, which occurred in village hamlets throughout Hungary, rather than the character “Hamlet” in Shakespeare’s play.

[ii] Commedia Dell’Arte is a form of professional theatre that began in mid-16th century Italy. It is defined by such innovations as an improvisational performance style based on brief sketches and story scenarios and masked character “types.” These wandering theatrical companies consist of troupes of actors, each actor having specific performance roles and support functions. The form became even more popular in France and eventually spread throughout Europe, where the tradition continues to the present day.

Ivan Szendro earned his Diploma in Theatre Acting in 1968 in the strict disciplinary environment of the Theatre Academy of Budapest, receiving an official appointment as an actor of the second National Theatre of Hungary in Szeged. While performing on the official stage, he also formed a wandering theatre troupe, Tanyaszinhaz (Hamlet Theatre), a free-spirited village-based folk theatre that was eventually suppressed by the Hungarian government. During his wandering years with the Hamlet Theatre, he encountered a small community in Szatmar, a remote part of Hungary, where he learned an ancient Hungarian myth, the Judge of Blood, which arose out of Hungarian indigenous shamanic tradition. His encounter with the myth launched his journey as a healer and “Myth-Carrier Shaman” (Coreopsis, Vol. 1, Number 3). He currently lives in Snedens Landing, Palisades, NY, where he continues his work developing a unique method of healing, called “The Legend of You”, his modern reinterpretation of the ancient shamanic healing approaches for the modern world. Ivan can be contacted at TheLegendofYou@yahoo.com. Excerpts from his award-winning “auto-mythography,” Self-Made Shaman, can be viewed at www.YouTube.com.

The interviewer, Ronald L. Boyer, is a scholar, teacher, and award-winning poet, fiction author and screenwriter. He is currently completing his M. A. in Depth Psychology at Sonoma State University in Rohnert Park, California, where he taught his first university course, “Mythic Structure in Storytelling™”, a creative writing course grounded in the archetypal theories of Carl G. Jung and Joseph Campbell (syllabus available at www.sonoma.academia.edu/RonaldLBoyer). While completing his graduate studies, Boyer presented an academic paper, “Introduction to the Mythic Orphan: Archetypal Origins of the Hero in Mythology, Literature and Film,” at the first Symposium for the Study of Myth, co-sponsored by Pacifica Graduate Institution, OPUS Archives and the Joseph Campbell Foundation. He will also present at the forthcoming conference of the International Association of Jungian Studies on the topic of “To Die, and Be Reborn: The Death-Rebirth Archetype in Myth & Rite, Literature & Film”. Boyer is also a graduate of the Professional Program in Screenwriting at UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television. A two-time Jefferson Scholar to the Santa Barbara Writers Conference, and two-time award-winner from the John E. Profant Foundation for the Arts, including the McGwire Family Award for Literature, Boyer’s poetry has been featured in the peer-reviewed scholarly e-zine of the Jungian and depth psychology community, Depth Insights: Seeing the World with Soul (Issues 3 and 5, Fall 2012 and 2013), Mythic Passages: A Magazine of the Imagination (January 2008) and many other publications. He will begin doctoral studies this Fall in the PhD in Art and Religion program at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, CA.