In Performance Theory (1988), Richard Schechner established a significant relationship between theatre and ritual. He wrote, “Whether one calls a specific performane ‘ritual’ or ‘theatre’ depends mostly on context and function…where it is performed, by whom, and under what circumstance” (Schechner, 1988, p. 120). This insight has deeply influenced my teaching of theatre and acting. In this essay, I outline how ritual informs my pedagogical practices. I emphasize the importance of practice and the ability for the study and performance of ritual to empower students with new insights about themselves and the world around them. Theatre has the power to make manifest upon the stage whatever stories one can imagine. Peter Brook calls this Holy Theatre, or calls “the invisible-made-visible” (Brook, 1968, p. 47). Theatre and ritual share this ability to make the invisible visible, and this key insight drives my teaching practices.

Keywords: theatre, ritual, acting, teaching, arts, pedagogy, Victor Turner, Richard Schechner, coffee

My approach to the study, teaching, and practice of theatre-as-ritual/ritual-as-theatre follows the methodology of theatre/archeology, especially as expressed by Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks in their 2001 book on the subject. As a practitioner-theorist, I occupy an insider’s vantage, which often results, as in the case of the present essay, in an exercise in autoethnography. I am especially interested in Pearson and Shank’s idea of performance practice and research “as a triangular field of attention which includes at its apexes the terms ‘practice’, ‘context’, and analysis’” (Pearson & Shank, 2001, p. xiv). They describe performance as an ecology, writing, “Site, as a concept, must be connected with place and locale, as the natural and cultural are entwined in a true ecology” (Pearson & Shank, 2001, p. 55). My classroom practice and this description and analysis of such, is rooted in the ecology of the classroom experience and the moments created therein. It is my intention that this document reflect this approach.

Photo 1: A scene from my 2011 production of Antonin Artaud’s Jet of Blood. Every part of the play was staged as a ritual. In this scene, the character of the Young Man meets the Virgin. Shown are actors Jessica Drake and Richard Keay. Photo provided by Lake Erie College (Photographer Robert Zyromski).

These discoveries, these estrangements, these epiphanies that reveal the world to participants can create a new consciousness in the student. Awareness of qualities and values that may have been as hidden as the stones themselves before exploration. In this sense, art is a process. For students in any arts class or workshop if the journey they experience is to learn to make the stones around them strange, then the stones must come alive. Art is totemistic, whether literally or metaphorically, so one must attempt to find the stories in the stones themselves and recreate them for an audience who has never noticed this strange stoniness that was always there but previously invisible.

Making the invisible visible and the silent speak is both a power and a responsibility in art. Martin Heidegger (1971) suggested that classic-era religious temples create a space where the gods can be present: “a Greek temple…encloses the figure of the god, and in this concealment lets it stand out into the holy precinct through the open portico. By means of the temple, the god is present in the temple. This presence of the god is in itself the extension and delimitation of the precinct as a holy precinct” (Heidegger, 1971, p. 67). Can we teach students skills that will allow them to make the gods around them present? Can we ourselves learn to make stones stonier and stranger than we ever imagined? In over twenty-five years of teaching, if there is any topic that can lead at least some students into unexpected epiphanies, as well as unexpected artistic expression, it is the study of ritual.

I recall in graduate school a teacher asking the class what we thought ritual meant, and in my mind, I thought about religion, and things like funerals. However, before I could speak several other students spoke up, and what they said surprised me: drinking coffee and brushing their teeth were rituals to them! Since then I have asked the same question many times to my own students and always some students bring up these seemingly mundane topics. And yet, what do funerals, wedding ceremonies, and graduations have in common with daily rituals such as drinking your morning coffee? What connects the celebratory with the mundane that might make both types of acts “rituals”? (Making the coffee strange, indeed!)

This is a great question for a class, perhaps for a discussion, a seminar, or group work. I love to see how students attempt to answer this. What similarities and differences can they identify? My main topic as a teacher is acting, and, although I can teach any major sub-genre of acting, I am especially invested in teaching viewpoints and movement training combined with creating original work in the form of what is known as devised theatre. (I have published a separate manifesto on devising: “I eat my words: a manifesto on Devised Theatre.” (Karawane, or the Temporary Death of a Brutist, Issue 9 2007, pp. 55-57).

I mention this now to say that when I begin a unit on ritual my lesson plan usually culminates in one or more performance pieces based on the study of ritual. So, what might begin as a classroom discussion about “What is ritual”? and “How are both funerals and drinking coffee rituals?” is building towards a goal for my students. This might be a one-off workshop, or this could be the beginning of weeks of exploration and performance activities. (I also sometimes use this same approach in my own productions as a director. Please see insert for a brief example.) Students who remain inspired to further study the nature of ritual will also eventually learn that anthropologists and other experts debate amongst themselves what does and does not count as such. With my ultimate goal of creating performance work as my guiding pedagogical brief, I would like to sketch out the next few steps I often employ and then end with a specific example of using ritual to create a performance.

Although a great deal has been written about ritual, when I teach the topic I rely on two well-known authors: Victor Turner and Richard Schechner. In the interest of brevity, I will not expand in detail about the two men’s work (I am sure it may be familiar to some of you and if not, I encourage you to check them both out). I mention them now because over the next few paragraphs, I will be using some of their terminology and I wanted to acknowledge their influence.

Beginning with my initial questions that grew from “what is ritual?” I usually have my students’ brainstorm lists. They may do these in small groups or perhaps just as the class together. I might ask them to list things they think count as rituals, and this is where things like “funerals” and “drinking coffee” et al are brought up. I usually follow this with a second brainstorming activity: based on the types of activities they have listed, I challenge them to describe the features that make them rituals. I usually write their ideas on the board so the class can keep track of our ideas.

An exhaustive list of things students might come up with (perhaps with some guidance from me) could be quite long, but things that always get mentioned include that both time and space are a little different. (“Going to a church” is an example of special place while graduations happen a “at the end of the year” is an example of special time, and so forth). One’s mindset is a little different (you know you are graduating or you know a birthday party is to celebrate someone); and although something literal is happening there can be quite a great deal of metaphoric value to what is going on. Examples of elements with metaphoric value include religious iconography (crosses, symbols, art objects like stained glass windows) or special clothes participants wear (graduation robes or a priest’s garb). Further, some rituals seem to have scripts with plots and dialogue like wedding vows as well as other theatrical elements (props, stages, even characters in some cases). This is our attempt to examine ritual like stones and try to find their stoniness—or their ritualism.

As a college teacher most of my students are young adults who have recently experienced their own high school graduation ceremonies and look forward to someday graduate from college. Let it be noted that anthropologists often draw distinction between ceremonies and rituals. For example, in The Anthropology of Performance, Turner (1988) emphasized that ritual create and celebrates community, while ceremonies, such as military parades, celebrate “structure since it is a symbolic representation of power” (Turner, 1988, p. 49). Nonetheless, students often show interest in discussing graduations as a living, familiar example. We discuss aspects such how as in graduation ceremonies, time and place are both special, at a set time and in a particular place, family, friends, perhaps a community, will gather to participate in this public ceremony. In a highly reductive sense, all that is happening is a public acknowledgement of graduating, so there is a very literal-minded aspect to the ceremony, something very practical in fact.

Of course, so much more is happening as well. Two important features include all of the mythical symbolism that is involved. A celebration of education, all the robes and speeches, and ceremonial ritual elements such as walking the stage, receiving a diploma, and moving ones tassel to the other side of the mortar board. Actions like these have symbolic meanings that acknowledge traditions and values. This includes scripted elements; the ceremony has a plot and dialogue in the Aristotelian sense. Secondly, a graduation ceremony has many of the key features Turner (1988) describes in a rite of passage: “separation from antecedent mundane life; liminality, a betwixt and between condition…to effect transitions from social invisibility to social visibility…from junioity to seniority” (Turner, 1988, p. 101). Students receive a change of status, from student to graduate. Since this is a public event, the community is being appraised of this change in status. Using this space as a locale for such a rite of passage makes both the use of space and time “liminal”, a transcendent time where rules may be different and social norms are bent to match the relative solemnity of the ritual at hand.

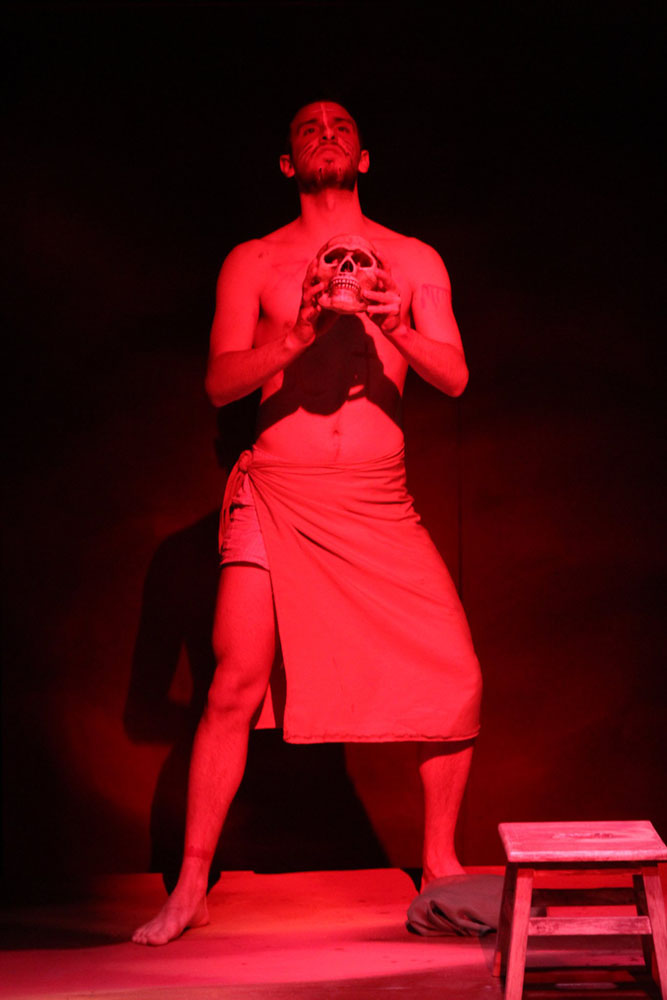

Photo 2: A scene from my 2011 production of Antonin Artaud’s Jet of Blood. Every part of the play was staged as a ritual. We depicted the character of the Knight as a Shaman who orchestrated the rest of the ritual. Shown is actor Brandon Shroud. Photo provided by Lake Erie College (Photographer Robert Zyromski).

With these features in mind, I invite students to consider if any such features typify the ritual of a morning cup of coffee. Is this a ritual? There is usually a special place or time. If either is missed then some may not feel like themselves. There is a step-by-step process that needs be followed; the making of the coffee and the selection of the proper cup. This is usually a private or domestic space and might involve others or may be alone time. There are usually no overt aspects one might call religious, spiritual, or mythic, and there is no obvious change in social status, so perhaps one would not want to describe having a cup of coffee as a rite of passage.

Hold that thought, however. There are almost certainly some mythic elements in play for a person who self-identifies as needing a cup of coffee in the morning. For example, food can be culturally specific, so one culture’s cup of coffee might be someone else’s alternate beverage (German beer? Japanese green tea? etc.). In addition, food is greatly associated with things like self-image, body image, and social status. Furthermore, many rituals incorporate food or drink as part of the experience. Which type of coffee you drink may say a good deal, about who you are, who you think you are, and what others think of you. Moreover, there may not be a literal change in one’s social status (like when a student becomes a graduate in the eyes of their community) but there is a tangible psychological change: for my hypothetical coffee lover, they are two different people, the before-coffee person and the after-coffee person.

Turner, Schechner and others have a term for social moments or events that have some rites-of-passage qualities but lack the full ritual transcendence, especially in a modern and commercialized world where money transaction often plays a role. They call some of these events liminoid. Turner (1982) wrote, “In the so-called ‘high-culture’ of complex societies, liminoid is not only removed from a rite de passage context, it is also ‘individualized'” (Turner, 1982, p. 52, italics and internal quote marks Turner). Twenty-first century theatre and sporting events may be considered liminoid social events. Drinking your morning coffee has all the requisite features of a contemporary liminoid event.

Having thus discussed with my students rituals in this manner and through several brainstorming activities (and please note, especially for upper-level classes, they would be doing some reading as well!) I will move the class from discussion to activities and later from activities to some form of final performance. Doing activities is one of the joys of teaching acting classes. Getting the students on their feet doing things is not only energetic, engaging, and joyful, but also very productive, because students are forced to put their ideas into actions. On a side note, I have taught numerous liberal arts classes over the years as well as visited other people’s classes on a variety of subjects (from history to philosophy, from mathematics to gender studies, and others). In every one of them, I have said these words: “everybody on your feet” and made them do acting exercises as a mode to explore whatever we were studying that day. I would encourage any teacher to explore acting exercises as a way to engage your students.

Carrying on, I cannot explain the hundreds of particular exercises one might do, so allow me to pick one excellent example and briefly describe how it intersects with teaching ritual. In Augusto Boal’s book Games for Actors and Non-Actors he describes an activity he calls “the great game of power” (Boal, 1998, p. 163). To summarize, students are tasked to position several chairs and maybe a few other props into arrangements that represent power. Usually there is one object (a water bottle or something similar) that is said to physically embody the theme of power. The students take several minutes to rearrange these items until everyone in the group is satisfied. The teacher usually takes it apart and makes them repeat two or three times, time allowing.

Eventually the students are asked to become part of the arrangement (I try to describe it as a three dimensional sculpture, as one might see at a museum). Therefore, when I ask the students to join in they must strike poses and hold them for a while, because they are like statues at this point. As each joins, one by one, I give them a little challenge to often make their pose the most powerful one so far, but sometimes I offer other provocations (be the least powerful, be in love with another character, be sad, and so forth). When everyone has a pose, you can stop there and debrief the experience, or there are further levels where you could activate the actors such as with movement, objectives, lines of dialogue, and the like.

Within the game of power, one can add in any of the elements discussed in your brainstorming and classroom discussions. Add elements of ritual, ceremony, rites of passage. Although “power” is the most typical theme of this game, you could make an exercise to create arrangements about funerals or weddings, or of sacred locations, churches, graveyards. If specific lines of dialogue or poetry from rituals have been identified, then those could be added in. For example, do the great game of power but when everyone is in their pose, you can instruct them that each actor gets one line of dialogue, and it must be something one might hear at a wedding.

The above brief description of Boal’s “the great game of power” exemplifies how one might extend the group’s exploration of “what is a ritual” into activities. Doing an on-your-feet activity, making physical and verbal decisions, encourages the students to experience the question with their bodies and actions. Moreover, such exercises prepare them for what will eventually come next, meaning creating a performance based on ritual. Having done this for many years, I personally have many ways I might accomplish this. In some cases, I will make it explicit that they are inventing an original ritual. In other cases, I might frame it more as a performance with ritual elements. As mentioned above, I sometimes use similar techniques while directing. For example, my own productions of Antonin Artaud’s Jet of Blood (see insert) and my Shakespearean adaptation called Tribal Titus were both fully realized through a rehearsal process based on the exploration of ritual and performance.

To digress with an example, in Tribal Titus, I recall fondly a scene we devised in which each actor had to recite the line “O grandsire, grandsire! Even with all my heart / Would I were dead, so you did live again! / O Lord, I cannot speak to him for weeping; / My tears will choke me, if I open my mouth” in a solemn and ritualized fashion as each added a chair to an altar they made, all in slow motion. Many in the audience found this “original ritual” very moving, even a couple who wept.

Given that I am most often teaching theatre classes, one of the things that most fascinates me is how much in common the performing arts (not just theatre) have with religion and ritual. In Performance Theory (1988), Schechner has explored this in great depth. “Whether one calls a specific performance ‘ritual’ or ‘theatre’ depends mostly on context and function…where it is performed, by whom, and under what circumstance” (Schechner , 1988, p. 120). Occasionally very religious students find these comparisons uncomfortable, but the vast majority of my students over the years have found this discussion both interesting as well as highly relevant to the study of theatre. With this in mind, let me give you a brief example of a performance project a class can do.

In my 100-level classes, the amount of time I might spend explicitly on ritual will only be one to three classes. Those will usually be early in the term, thus allowing me to bring it up frequently later on. However, during those introductory days I will usually have the class do some kind of in-class ritual-based performance. If it is a typical class with ten to thirty students, they will be broken up into small groups of approximately three to five. Going to my blackboard where we have just spent time brainstorming as described above, I will review all the words up there and then give each group several words off the board. One group might get “birthday party, ceremonial hats, fire” while another group gets “gongs, sacred ground, the line ‘I do'” and so on. With their groups and their key words, I will tell them that must create their own ritual. They will usually be given a time limit of ten to twenty minutes at most, to create this ritual. Sometimes this might be all the instructions I give them, other times I feed them more provocations. As an example; I have more than once told the class the Shinto story of the Sun goddess Amaterasu, who refused to come out of her celestial cave and so the other spirits and gods “put on an entertainment, including dancing, which brought her out of the cave and thus returned light to the world” (Recounted in Shinto: The Kami Way by Tokyo Ono and William P. Woodard, p. 4). With that story or something similar, I might give them a little material to help them shape their performance.

This activity culminates with a quick, in-class performance. Before this, I circulate amongst the groups to see if I can help them or otherwise answer any questions. Because the activity is outside the wheelhouse of most of the students, (especially if it is a 100-level class) there is always some uncertainty, so I try to be reassuring. I also push them to practice! Get on your feet! They must to get out of the ideas-generating-stage and into the ideas-testing-stage as quickly as possible. I usually push them to make their performance more ritualized and to add more elements that are symbolic. Even simple suggestions like, “Do this portion in slow motion” or “That cap you’re using, it’s not just a cap, it represents your god” or “Try singing or chanting”, suggestions like that push them to be more creative and daring in the making of their original rituals. Let me add I am always excited, and sometimes even proud, to watch the presentations at the end of a class like this.

In The Empty Space Peter Brook (1968) wrote about what labeled Holy theatre. For Brook, “Holy theatre” is not religious per se but more akin to what Brooks calls “the invisible-made-visible” (Brooks, 1968, p. 47). This is theatrical storytelling’s ability to make the invisible visible (gods and fairies, heroes and villains, our imagination writ large). The study of ritual in a theatre class tangibly demonstrates this nearly magical aspect of theatre by revealing its parallels in ritual. In fact, Brook identifies “four theaters”: in addition to holy, there is rough, immediate, and deadly. It is not worth summarizing his entire thesis here, but rough theatre is grounded, and is for and of the people. Immediate theatre emphasizes the experience of the now. Deadly theatre refers to theatre that is lifeless and without joy or purpose; it in effect reveals nothing while simultaneously repulsing its audience with dread. Ritual, I suspect, also comes in these four ways. A boring and poorly done old or traditional ceremony probably reveals nothing and closes down the audience’s imagination. However, in class, the creation of ritual-inspired performance pieces has the potential, not just to study these qualities, but also to experience them in action.

In the making of these types of pieces, we can urge the students to accept the rough edges and personal elements, even favoring them over a false sense of perfection. If the ritual is yours then it cannot ever be done wrong. This is empowering. Their original ritual pieces should also embrace the immediate: each element and each moment and each gesture or sound should be given its chance to contribute. Lean into and enjoy the expression of your ritualistic elements. Long pauses, slowed down movements, resonate chanting, these all happen in the now and have power in the now. The “holy” element of ritual makes what is in your mind, your heart, and your soul visible. This, of course, could have a religious facet in some cases, making the gods present, as suggested by the Heidegger quote above, but in class it is just the beginning of empowering yourself to take the blank canvas of the performance space and filling it with you. The story of the strangeness of the stones around you is also your story.

Photo 3: A scene from my 2011 production of Antonin Artaud’s Jet of Blood. Every part of the play was staged as a ritual. Here we see the Shaman and the Whore preparing the Virgin for her wedding. Shown are actors Brandon Shroud, Jessica Drake, and Tina Greenslade. Photo provided by Lake Erie College (Photographer Robert Zyromski).

A brief example—using ritual in productions in my 2011 Jet of Blood by Antonin Artaud.

For this production, I began with an audition process that emphasized improving skills and playfulness. I needed an ensemble that would be creative and have fun participating in a rehearsal process likely different from anything they might have previously experienced. For those not familiar with the play, you can find a version of it here: http://www.spurtofblood.com/.

Artaud is known for his study of the performances/rituals of Balinese dancers and the Taramahara peoples of Mexico. This play is meant as a surreal deconstruction of a love story, in which a young man is caught between a virgin and a whore. The play is known for its many wild elements and has been considered by some impossible to stage literally. For example, one stage direction calls for “A multitude of scorpions crawl out from beneath the Wet-Nurse’s dress and swarm between her legs. Her vagina swells up splits and becomes transparent and glistening like a sun.”

My approach was to treat the play text as a “holy” document and to invent rituals that would reveal the mystical nature of the text. Our adaptation became a sort of wedding ceremony in which the characters of The Young Man and The Young Girl are guided through a series of matrimonial ceremonies by a Shaman figure, a mother figure, and “the whore” character who in our rendition became a metaphoric embodiment of Sexuality. In rehearsal, we would take one bit of text at time, including dialogue and stage directions and come up with ritual moments for each. As a rehearsal process, it was very creative and joyful, although as a devised piece there was a time in the middle when some actors began to wonder how it would all come together. Going from exercises and improves to a final performance is one of the biggest challenges to successful devised theatre. In a personal e-mail, noted Artaud scholar Robert M. Connick called this production “a very interesting approach” that “seemed to hit on some of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty aesthetics.” There is a video of this performance available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cDzYdh7yabg

References

Brook, P. (1968). The Empty Space. London: Penguin.

Heidegger, M. (1971). Poetry, Language, Thought (Trans. Alfred Hofstadter). New York: Harper & Row.

Ono, S. (1962). Shinto: The Kami Way (in collaboration with William P. Woodward). Tokyo: Charles Tuttle Co.

Pearson, M. and Michael Shanks. (2001). Theatre/Archaeology. London: Routledge.

Schechner, R. (1988). Performance Theory. New York: Routledge.

Shklovsky, V. (1925/1990). Theory of Prose (Trans. Benjamin Sher). McLean Ill. Dalkey Archive Press.

Turner, V. (1982). From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. New York: PAJ Publications.

Turner, V. (1988). The Anthropology of Performance. New York: PAJ Publications.

Dr. Jerry Jaffe is Professor of Theatre at Lake Erie College. He has directed or performed in over 100 shows. Before coming to Lake Erie College, Jerry lived and worked in Japan and New Zealand, teaching, acting, and directing there. Many of his articles on the theatre have been published in various academic journals, including “‘I needed to go to this tabernacle of ignorance’: Marc Maron’s critique of the Creation Museum” (Bulletin for the Study of Religion, Vol 42, No 3 (2013)); and he co-edited the 2008 book, Performing Japan: Contemporary Expressions of Cultural Identity. From 2008-2010, Jerry served as a reader and member of the Editorial Staff- Coreopsis: A Journal of Myth and Theatre.

He recently created the Comedy Studies minor at Lake Erie College. Recent productions he has directed at Lake Erie College include Murder by Poe, Sexual Perversity in Chicago, The Jungle Book, Proof, and Almost, Maine. His production of Almost, Maine was called “Almost Perfect” in a local review. He also performs stand up comedy, in the area and around the country.