Abstract

Key words: archetypes, C. G. Jung, film studies, iconography, initiation, J. R. R. Tolkien, literature, Lord of the Rings, mythology, mythopoetics, Peter Jackson, psychology.

“Blessed are the legendmakers,” wrote J. R. R. Tolkien in his famous poem, Mythopoeia, “with their rhyme of things not found within recorded time” (Tolkien, 1988, p. 88). Since publication of this poem, and following the extraordinary commercial success that subsequently accompanied publication of Tolkien’s fantasy-genre literary epic, The Lord of the Rings [LotR][1] (Tolkien, 1994), the study of mythopoetics—derived from the Greek term mythopoeia or “myth-making”—has been typically associated in modern literary criticism with Tolkien and the speculative literary genre of fantasy. This paper examines how Tolkien, as a modern mythopoeic legend-maker or mythmaker himself, utilized pre-existing myths and mythopoeic symbolism in the creation of his own fictional mythology of Middle-earth.

According to the Mythopoeic Society, an international community of mythopoeic scholars and artists inspired by Tolkien and his fellow Oxford Inklings, individual definitions of what constitutes mythopoeic literature are diverse, but can be generally defined as:

literature that creates a new and transformative mythology, or incorporates and transforms existing mythological material. Transformation is the key—mere static reference to mythological elements, invented or pre-existing, is not enough. The mythological elements must be of sufficient importance in the work to influence the … lives of the characters, and must reflect and support the author’s underlying themes. (The Mythopoeic Society, “Mythopoeic Literature” par. 1)

This study examines Tolkien’s creative transformation of pre-existing, archetypal-mythological imagery in the creation of his fictional, literary mythology. It does so through the lens of Tolkien’s cinematic interpreter Peter Jackson in the critically-acclaimed epic film trilogy—LotR: Fellowship of the Ring [FotR], 2001, LotR: Two Towers [TT], 2002, and LotR: Return of the King [RotK], 2003[2]—based on Tolkien’s mythopoetic three-part fantasy novel. The study explores how Tolkien—via Jackson—incorporates and transforms “existing mythological material” in creating LotR. As a study of narrative motifs represented in visual iconography (i.e., cinematic, motion picture pictorial art), the paper examines archetypal, widely recurring myth-motifs of transformational, visual imagery supported by narrative text (i.e., narration, dialogue). By transformational imagery, the author refers specifically to ubiquitous primordial death-rebirth imagery of prehistoric origins[3] found in aboriginal myths and rites around the world. This cyclical death-rebirth imagery common to traditional mythologies the world over (Henderson and Oakes, 1963) was identified by depth psychologist Carl G. Jung in his essay “Concerning Rebirth” as a major psychological archetype, the rebirth archetype, or “archetype of transformation” (Jung, 1973, pp. 45-82).

Jung’s Rebirth Archetype

in Mythology and Cinema

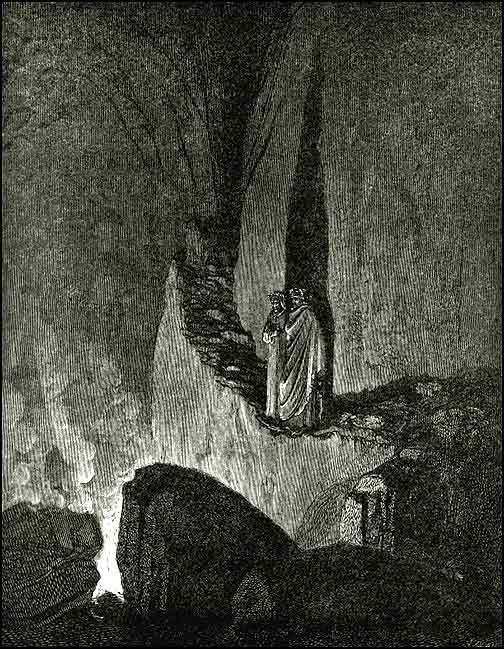

The rebirth archetype, identified and defined by Jung (Jung, 1991, pp. 202-265; 1973, pp. 45-81), has been subsequently explicated by a number of Jung’s successors over succeeding decades,[5] and is examined in detail in a number of published and unpublished papers by the current author, beginning in 2010 (Boyer, 2010a). Subsequent research demonstrates the trans-historical, cross-cultural, and trans-medial representation of the archetype which appears throughout world storytelling forms including mythology, literature, and film (Boyer, 2015c). The archetype has been further studied by this author as represented in the mythopoeic ancient literature of the Old Testament (Boyer, 2017), the religious cinematic interpretation of the New Testament (Boyer, 2014), folk and fairy tales (Boyer, 2017), the mythopoeic medieval literature of Dante (Boyer, 2020), and the visionary literature and pictorial art of William Blake (Boyer, 2015a).

This rebirth symbolism is an example of what Jung called “archetypes,” or primordial images of a collective nature, widely distributed in cultures throughout the world since ancient times. The rebirth archetype is an extremely common or conventional narrative metaphor presumably based on the cyclical imagery of nature and widely evident in ancient mythologies and their ritual counterparts around the world. Jung and post-Jungian scholars identified these symbolic motifs as mythico-ritual, literary, and psychological archetypes. The myth-motif represents, according to this author, an essential foundational symbolism of both primordial indigenous oral traditions and more modern literary myth-making—for example, in the mythopoetic worlds created by Dante, Shakespeare, Blake, and Tolkien—that remains insufficiently documented in the literature, in particular as it is depicted in the popular mass media forms of cinematic and TV narrative storytelling.[6]

Rooted in the Jungian perspective—including major interdisciplinary scholars influenced by Jung, especially Joseph Campbell, Mircea Eliade, and Northrop Frye—this paper examines evidence of the widely recurring imagery of death and rebirth, an archetypal feature of storytelling that has survived the cultural-historical transformations of millennia and is commonly embedded in the symbolic imagery associated with modern-day cinematic heroes. The paper discusses the archetype, a common myth-motif and primordial image of transformation, as it appears in Tolkien’s epic novel, interpreted in contemporary cinematic narrative and iconography by filmmaker Jackson.

The study demonstrates that symbolic death and rebirth imagery appears as a major thematic thread supporting the entire narrative of Jackson’s film trilogy, LotR, adapted from Tolkien’s original text. The motif is evident on several levels in Tolkien’s tale, for example, in its explicit representation as a transformative moment in the lives of its main, major, and even minor characters, in its overall symbolic topographical setting depicted as an archetypal hero nekyia journey of descent (to the symbolic Land of the Dead) and return with new life, and more generally in the trilogy’s conventional dramatic structural arc as a whole—a conventional structure of mythico-ritual narrative describing the archetypal journey of the mythical hero-initiate into the depths and subsequent return to new life that has represented the symbolic structural backbone of theatrical tragedy and narrative drama at least since Aristotle’s Poetics (Aristotle, 1997), which was based on earlier mythologies and embedded in the conventional tripartite structure of dramatic contemporary storytelling in the form of the 3-act play.

This age-old symbolic imagery is evident in the transformational trajectory of LotR’s main character, the Hobbit[7] Frodo Baggins, who undergoes a series of initiatory encounters with Death, ultimately triumphing through a series of symbolic rebirths culminating in his passage to the Undying Lands known as the Grey Havens. Frodo’s journey is a fine example both in modern literature and cinematic storytelling of Campbell’s classic hero quest myth of “down-going and upcoming,” that is, of departure, initiation, and return described by Campbell as the narrative trajectory of the hero quest or “leitmotif of the monomyth,” adapted from the kathodos and anodos structure of ancient Greek ritual theater (Campbell, 1973, pp. 28 and 30). Using the terms of his Uncle Bilbo’s autobiographical memoir, Frodo’s heroic quest is a journey “There and Back Again”—a symbolic journey to the Land of Death and back again with new life.

A Note on Theory, Method,

and Key Terms

Theoretical perspective and methodological considerations. The hermeneutical approach brought to the material is grounded in an interdisciplinary perspective rooted in the theories of depth psychologist Carl G. Jung and major scholars influenced by Jung, most notably Joseph Campbell (comparative mythology/literary mythology), Mircea Eliade (history of religions), and Northrop Frye (archetypal literary criticism or myth-criticism), as well as their earlier interpretive sources, including Sir James Frazer (Frazer, 1963), Arnold van Gennep (van Gennep, 1975), Jessie Weston (1957), and other pioneering scholars.

In as much as Tolkien was a devout practitioner of Catholicism, much of the Tolkien research has emphasized the underlying theology of Tolkien’s iconography. This study offers a psychological and myth-critical hermeneutical perspective that represents an alternative to theological approaches. This perspective yields psychological meaning independent of Christian faith traditions, whereas the conventional theological hermeneutic offers literalistic, faith-based interpretations of Tolkien’s works. As mythologist Campbell suggests, “theology is mythology interpreted literally” (Campbell, 1990, p. 33). He continues: “Mythology is psychology, misread as cosmology, history, and biography.” This paper approaches the subject of Tolkien’s imagery from this non-theological perspective, that is, as psychological metaphor using natural cyclical imagery analogous to unconscious psychological processes and possessing contemporary relevance to psychological transformation and development. The iconography is viewed as a locus of psychological meaning as well as literary and cinematic narrative meaning.

Method of analysis. The original research method that led to the author’s current focus on rebirth imagery as archetypal symbolism was inspired by Jung’s analytical method called “amplification.” According to Jung, amplification—a type of hermeneutical function—consists basically of the analyst’s observation of recurring symbolic motifs as they appear in analogous forms, for example, in myths, dreams, fantasies, art, etc. As a literary study, the method of narrative and textual analysis (i.e., word and image), separated out for critical commentary as distinct units of the story, emphasizes amplification (in the Jungian sense) of text (narration, dialogue) and cinematic pictorial imagery, that is, visual iconography in Tolkien’s original artistic illustrations as well as its popular film adaptation by Jackson. It should be noted that any critical description of film narrative, as mere synopsis or abstraction of the imagery, is at best a pale representation that lacks the emotional impact of the cinematic pictorial art. The interested reader is encouraged to view the films in their entirety for a more vivid understanding and direct experiential impact of death-rebirth imagery conveyed in the films themselves.

Definition of key terms. For purposes of this essay, rebirth imagery is primarily defined (in specific units of pictorial imagery) as the apparent or presumptive death of a character as experienced either by the audience and/or other characters within the fictional narrative itself. Yet, immediately thereafter (or perhaps much later in the tale) the dying or presumably dead character recovers or reappears having somehow miraculously survived. In cinema, this effect is often produced by editorial craft devices. For example, a scene is cut where a character appears unconscious and/or possibly dead, but in a later scene wakes up or reappears still alive; or the character might appear as a presumed corpse that subsequently moves and opens its eyes or sits up—an example of what myth-critic Northrop Frye describes as “displacement” (Frye, 1963, pp. 21-38;1990, pp. 136 and 155-56). This will become clearer in the commentary on specific imagery that follows.

Findings and Discussion: The Symbolic-Initiatory Deaths and Rebirths of Frodo Baggins

Mythopoeic authors like J. R. R. Tolkien often use such archetypal symbols, essential elements of the vocabulary of mythmaking, to create mythical fictional worlds like Middle-earth in The Hobbit and LotR. In ancient myths, the archetypal orphan-hero typically experiences symbolic death and rebirth in some form. Frodo Baggins is no exception. In the trilogy of LotR, the main character—the narrative orphan-hero, Frodo—comes close to dying regularly, and appears to die on a handful of occasions. In this cinematic iconography, explicit initiatory imagery is apparent. The complete arc of the ritual initiate (or shamanic initiate), according to religious historian Eliade, is death-rebirth (or resurrection). Frodo, in multiple distinct moments in the film trilogy adapted from Tolkien’s literary tale, experiences death and rebirth, the traditional initiatory schema interpreted by Eliade (Eliade, 1958; 1974) in numerous works on the subject.

Initiatory Death by Wounding with the Poisoned Blade of the Witch King

Frodo Baggins is a classic mythological hero in the sense originally discussed by Jung in his first book, Psychology of the Unconscious, in his discussion of the sun-hero in world mythology (Jung, 1991, pp. 187-201). Jung’s model of the sun-hero—a figure whose narrative arc imitates the cycle of the setting and rising sun—was later amplified by comparative mythologist Campbell in the creation of his narrative paradigm, the archetypal hero quest, detailed in Hero with a Thousand Faces (Campbell, 1973). Frodo is the main hero and the principal savior-redeemer of Middle-earth, slightly greater than his peers among a trinity of mythic heroes, including the mortal warrior-king, Strider/Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen), and the supernatural mentor, psychopomp, and Wizard, Gandalf the Grey/White (Ian McKellen).

Frodo’s hero quest initially begins as an archetypal journey in a setting of another world. In Tolkien’s literary text, Frodo tells his Hobbit friend, Pippin, at the beginning of their quest: “The Road goes ever on and on/Down from the door where it began” (Tolkien, 1994, p.72). The first level of descent down into the depths occurs, as it did for the character Dante in The Inferno, as Frodo’s path departs from the ordinary daylight world of the idyllic Shire into the depths of an ominous and darkened wood, following the route into the depths taken by Dante (Boyer, 2019). “Do not go where the path may lead,” says the popular quote widely attributed to Ralph Waldo Emerson.[8] “Go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.” This is the well-known “pathless path” taken by countless journeying and questing heroes since antiquity, and the metaphor is particularly evident, as mythologist Campbell points out, in the medieval Romance legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Roundtable, who venture off into perilous regions on pathless-paths leading through deep and often enchanted forests.

The hero Frodo’s first symbolic death, or initiation, occurs in the dark depths of such a forest. The depths depicted as a forest journey motif, it is worth noting, is a central topographical depth image used throughout the entire mythic adventure. Tolkien’s heroes (and Jackson’s) venture, at various stages of the quest, through the Old Forest, as well as Lothlorien, Fanghorn, and Ithilien Forests. In Jackson’s films these forest journeys are depicted in various scenes throughout the trilogy (Jackson, 2001, Ch. 10; 2002, Chs. 8, 14, 21, and 31). Mirkwood Forest is a major setting in Tolkien’s original literature.

Fig. 1. Entering Mirkwood by Ted Nasmith. This Tolkien-inspired artwork by Nasmith conveys the archetypal imagery of the hero quest via descent into the depths of an old forest typical of the medieval Grail romances. Tolkien’s own abstract impressionistic rendering of Mirkwood (Hammond and Skull, 1995, p. 88) does not do justice to the symbolism. Used by permission of artist Ted Nasmith. www.tednasmith.com

Bilbo and his Hobbit companions first enter this symbolic terrain near the mid-point of the initial film in Jackson’s series, LotR: FotR. (2001). The event is significant, driving the plot for a large remaining segment of the film. The critical moment occurs after Frodo and his companions depart from the Dancing Pony Inn at Bree, near Brandywine Crossing. The party is now comprised of Frodo, his sidekick and gardener Samwise “Sam” Gamgee (Sean Astin) and their Hobbit companions, Peregrin “Pippin” Took (Billy Boyd) and Meriadoc “Merry” Brandybuck (Dominic Monaghan), accompanied now by the mysterious Ranger known as Strider (Mortensen).

The companions initiate their journey with a hike through the deep woods of the Old Forest en route to Elvish lands. The party is hotly pursued through the forest and attacked by Death, personified in the figures of the “the Nine” Nazgul or Ringwraiths, disguised as “Black Riders” unleashed by Lord Sauron to kill the Ring-bearer and secure the One Ring.

Fig. 2. Early in the adventure, Frodo is stabbed and seriously wounded by the Witch-king’s poisoned blade. Screenshot courtesy of New Line Cinema and Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

After an exhausting and perilous escape from the Inn, the companions spend the night resting and hiding at an abandoned ruins, the “great Watchtower of Amon Sul” (aka “Weathertop”), where the Ringwraiths surround them (Jackson, 2001, Ch. 15). The cinematic iconography vividly portrays Frodo’s first initiatory, direct symbolic encounter with Death. During the fierce battle, Frodo puts on the Ring to hide, but the Ringwraiths—led by the Witch-king of Angmar, Lord of the Nazgul—surround him. In a dramatic scene, one of the Ringwraiths, presumably the Witch-king, plunges a sword blade into the not-quite-invisible Frodo’s upper chest, (apparently) mortally wounding him. Eventually, Strider drives off the Nazgul and rescues Frodo, but still fears for the fallen Hobbit-hero’s life. “He’s been stabbed by a Morgul blade,” Strider—a gifted shaman or natural healer—warns the other Hobbits. “This is beyond my skill to heal. He needs Elvish medicine.” In a subsequent scene in this storyline, the dialogue reinforces the death imagery as Sam observes the fast-dying Frodo. “He’s growing cold. Is he going to die?” Sam asks Strider. Strider replies: “He’s passing into the Shadow World. He’ll soon become a Wraith like them” (Jackson, 2001, Ch. 17).

Soon, the Elven-princess Arwen (Liv Tyler), daughter of Lord Elrond (Hugo Weaving), appears to the dying Frodo. “I’ve come to help you…. Come back to the light,” she instructs Frodo. Arwen examines his wound. “He’s fading,” she warns the others. “He’s not going to last.” The fastest rider in the group, she offers to take Frodo to Rivendell. A suspenseful ride through the forest ensues as she carries the apparently lifeless hero with the Ringwraiths in hot pursuit. Arwen beats their pursuers to the river that borders the lands of the Elves. Here, Elven powers protect her, sweeping the Black Riders away with a giant wave.

The next narrative sequence (Jackson, 2001, Ch. 18), which closely follows the original literary text, shows Frodo alive again, awake and recovering—safe in a bed, in a numinous light-filled room. “Where am I?” he asks Gandalf. “You are in the House of Elrond,” Gandalf replies. Gandalf’s dialogue with Frodo reinforces the imagery of the Hobbit-hero’s near-death and remarkable recovery: “I’m here. And you’re lucky to be here, too,” says Gandalf. “A few more hours and you would have been beyond our aid. You have some strength in you my dear Hobbit.” In a later scene continuing the storyline at Rivendell (Jackson, 2001, Ch. 20), Gandalf discusses recent events and the fate of the Ring with Lord Elrond, who decides to convene a Council. During their dialogue, Gandalf amplifies his observation of Frodo, telling Elrond that Frodo would have died in a few more hours and that his wound will never truly heal. “He will carry it the rest of his life.”

Other imagery suggesting Frodo’s miraculous healing and regeneration follows as he is joyously reunited with his Hobbit companions, including his uncle and foster father Bilbo (Ian Holm) who has noticeably aged without benefit of the regenerative powers of the Ring. Frodo, initiated and about to be transformed into the reluctant Ring-bearer and hero of the adventure, miraculously survives the near-fatal initiatory wound that threatened to end his life, and the quest itself, before it really begins. This is the first of several near-death and miraculous healing experiences for Frodo in which death-rebirth imagery is explicitly pictured. Frodo recovers and returns to life transformed, about to become Ring-bearer. And his adventurous journey to Rivendell is about to be transformed into a heroic quest to save Middle-earth from apocalypse.

At the subsequent Council meeting called by Elrond, who magically restored Frodo to life, the heroic Quest to destroy the Ring of Power is decided upon, and Frodo reluctantly (Campbell, 1973, pp. 59-68) volunteers to carry the Ring to Mordor and Mt. Doom, completing his initial transformation from fearful Hobbit to heroic Ring-bearer, the savior-redeemer figure of the entire LotR. At the Council meeting, a “Fellowship of the Ring” is formed, adding to the four original Hobbit companions Gandalf the Grey, Strider (whose true identity is now revealed as Prince Aragorn, Isildur’s heir and rightful King of Gondor), the Dwarf Gimli of Gloin (John Rhys-Davies), the Elf Legolas (Orlando Bloom), and a second mortal, Lord Boromir of Gondor (Sean Bean).

Apparent Death

by Stabbing in the

Depths of Moria

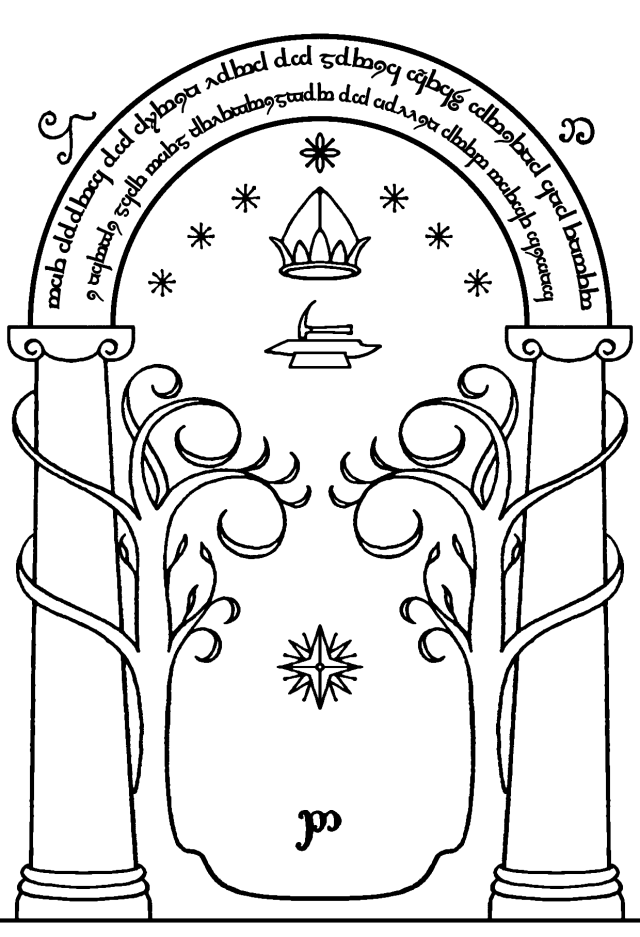

Frodo’s second initiatory death and rebirth occurs during the first major action of the Fellowship’s new quest to return the Ring to Mt. Doom. In this part of the story, not long after setting out, Frodo, Gandalf, and the Fellowship are forced by Saruman’s magic to make a perilous passage through the symbolic underground depths of another world, represented in the form of the subterranean mines of Moria (Jackson, 2001, Ch. 26). Guarding that passage is the Door of Durin, a symbolic portal image marking the transition into the depths of a liminal (Turner, 1992, pp. 29-47 ad 48-55) underworld that awaits them on the other side of the Door. The Door itself is a subject of Tolkien’s own illustrative iconography, an image faithfully, visually represented in Jackson’s film. While the symbolic significance of a hero’s passage into the depths of an archetypal forest can be subtle and easily overlooked, a clearly marked portal or gateway image like the Door of Durin more obviously marks a threshold passage (Campbell, 1973, pp. 77-89; Boyer, 2014) into another realm.

Fig. 3. Original illustration of the Door of Durin by J.R.R. Tolkien. Courtesy of the J.R.R. Tolkien Estate.

The dramatic entry into the subterranean caves of Moria introduces the important symbolic depth imagery of the classical Greek hero-nekyia, which Jung describes as a symbolic descent into the Land of the Dead, characteristic, according to Jung, of the hero’s nekyia into the Underworld (Jung, 1992, pp. 83-84; Boyer, 2019). Here, in Tolkien’s story visually interpreted by Jackson, the iconography conforms closely to Jung’s psychological description of the nekyia, or descensus ad inferos, and its symbolic analogue, the “night sea journey”:[10] “The night sea journey is a kind of descensus ad inferos, a descent into Hades,” Jung wrote, “and a journey to the land of ghosts somewhere beyond this world, beyond consciousness, hence an immersion in the unconscious (Jung, 1992, pp. 83-84).”

Immediately on the other side of the Door—the portal to a liminal underworld passage—the Fellowship members realize they have entered a symbolic Land of the Dead (i.e., Hades, realm of Death), Jung’s “land of ghosts.” As they enter the darkness of Moria, the iconography depicts the skeletal remains of fallen Dwarf-warriors all around them. “This is no mine,” Boromir observes, “It’s a tomb.” In archetypal picture-language, they have entered a symbolic Land of the Dead “somewhere beyond this world,” imagined by Tolkien in the form of a great underground crypt filled with fallen Dwarves. Their journey is taking them through a symbolic Hades-realm[11], where the dense darkness evokes a dire warning from Gandalf: “We must face the long dark of Moria. Be on guard. There are older and fouler things than Orcs in the deep places of the world” (Jackson, 2001, Ch. 28).

As they descend into this shadowy landscape in the dark depths of the earth, Gimli discovers the stone burial tomb of his cousin, Balin, illumined by a numinous ray of sunlight breaking into the darkness (Jackson, 2001, Ch. 29). Then Pippin accidentally awakens an army of Orcs and their belligerent allies, and the party is soon surrounded and attacked. A fierce battle takes place deep within the dark underworld landscape of Moria, as the hopelessly outnumbered Fellowship is surrounded and attacked by an underworld horde. During the dramatic action scene of the battle, shortly after Aragorn—defending Frodo—falls wounded and unconscious[12] as the battle reaches its climax, a giant Cave Troll powerfully thrusts its spear into the center of Frodo’s chest, apparently killing Frodo—a thrust that, according to Strider, would have “skewered a wild boar.” The Hobbit-hero once again lies motionless, apparently dead. No one, the event’s witnesses might naturally conclude, could survive such a thrust in that vital location.

Using cinematic devices, the scene is cut so that Frodo appears to be killed, presumed dead both by the characters in the story—his companions—and the viewing audience. Aragorn, who had also fallen in the battle, wakes up and crawls to Frodo’s body and, assuming that Frodo is dead, utters a spontaneous lament: “Oh no!” Fortunately for Frodo, and the story itself, this exclamation is countered in the next instant when Frodo moves and weakly groans. Sam observes the fallen Frodo closely. “He’s alive,” Sam declares. “You should be dead,” Aragorn tells Frodo. Then comes the revelation that Frodo has been miraculously saved once again, this time by his protective Elvish cloak of mithril, gifted to him by Bilbo in Rivendell (Jackson, 2001, Ch. 24). Frodo suddenly opens his eyes and revives, to the relief of his friends and the audience. He reveals the magical Elvish vest he was wearing beneath his clothes, a sort of mythopoeic fantasy equivalent of the armored vests worn by contemporary soldiers and law enforcement officers. What initially appears to be a second presumptive fatal stab wound—a second apparent death of the hero—is revealed, as the scene unfolds, as mere illusion created by editorial device. In effect, the hero wakes up as if reborn, and the narrative continues.

Fig. 5. Frodo lies apparently dead from the wound inflicted by a giant Cave Troll’s spear in the underground depths of Moria. Screenshot courtesy of New Line Cinema and Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

That Frodo’s second death and rebirth, briefer and less dramatic than the first[13], occurs during a classic nekyia (i.e., descent into the underworld realm of ghosts) is symbolically significant, as it amplifies the explicit foreground initiatory imagery (Frodo’s presumptive fatal wounding) against the implicit initiatory background iconography of the landscape setting (i.e., the subterranean underworld) in which the event occurs, that is, during descent into the Land of the Dead characteristic of mythological heroes throughout the ancient world. This can be understood—in the echo of the earlier wounding by the Witch-king’s blade coupled with the subterranean topographical setting of an archetypal descent to Hades—as a second initiation of the hero amplified by the archetypal landscape of death-rebirth depth imagery typical of heroic nekyia journeys. Here the hero is stabbed and apparently mortally wounded during a symbolic descent into the depths, this time, obviously, in a ghostly underworld realm.

Symbolic Death

by Drowning in

the Dead Marshes

Frodo’s third death and rebirth experience, subtler than the initiatory wounds already discussed, comes early in Jackson’s sequel, LotR: TT (2002). The second film picks up the tale following the dramatic and untimely death of Gandalf the Grey in the depths of Moria. Following that shattering event, Frodo—accompanied by Sam—leaves his companions to pursue the quest for Mordor alone, but now meets their guide and nemesis, the treacherous Smeagol, the Gollum (Andy Serkis). Smeagol agrees to act as their guide to Mordor, leading them into the depths of a swampy wasteland[14] towards Mt. Doom. Here Frodo has a third very intimate symbolic encounter with Death, echoing Moria in a distinctly re-imagined land of ghosts, an archetypal meaning suggested by the wasteland’s name: the Dead Marshes (Jackson, 2002, Ch. 12).

In this scene, Gollum leads Frodo and Sam, finding their way through the Dead Marshes to Mordor. On this third occasion of Frodo’s imminent death and miraculous rebirth, the hero journeys through a lifeless wasteland approaching Mordor, a swampy marsh littered with drowned, underwater corpses. The imagery suggests another nekyia journey into a symbolic land of ghosts, analogous to the iconography of the subterranean tomb entered through the Door of Durin. Like the encounter with the Barrow Wights in the original Tolkien text—an early clue to the descent journey into the land of the dead omitted from Jackson’s adaptation—and the classical descent into the underworld Hades-like mines of Moria, this moment further amplifies the nekyia imagery of symbolic hero-journeys in the Land of the Dead. “There are dead things. Faces in the water,” Sam observes of the passing underwater corpses as they walk. “Careful now,” Gollum warns, “or Hobbits go down to join the dead ones.”

Soon thereafter, Frodo makes a fateful error, glancing down at a corpse lying face up under the water. The corpse dramatically stirs to life, opening its lifeless eyes and beguiling Frodo. The enthralled hero, drawn by the siren song of the living corpse, falls forward, headlong into the watery depths. There the helpless Frodo is assaulted by terrifying spirits of the Dead and nearly drowns. Once again the apparently doomed and helpless hero miraculously survives, this time rescued at the last second by Gollum, who pulls the nearly drowned hero from the water. This iconography suggests a rite of baptism, in which the initiate (in this case, Frodo) is thrust under water (signifying or symbolizing death) and raised up again to breathe Virgil’s “upper air.”[15] In effect, Frodo dies and is reborn a third time in the adventure. Again, the Hobbit-hero survives and continues his quest, following this third all-too-close encounter with Death.

Symbolic Death

from Shelob’s

Poisoned Sting

Frodo’s fourth major initiatory transformation (i.e., death and rebirth) occurs in the third and final film of Jackson’s trilogy, LotR: RotK (Jackson, 2003). Frodo is tricked by Gollum into entering the subterranean caves and lair of the monstrous spider Shelob, where he is once again apparently fatally wounded—and about to be devoured (Jackson, 2003, Chs. 29 and 33).

Late in the last film of the trilogy, RotK, following Aragorn’s quest for aid on the Paths of the Dead[16], Smeagol leads Frodo—now separated from Sam by Gollum’s cunning—unknowingly into a trap, claiming it is a shortcut leading directly into Mordor. Frodo reluctantly enters the mouth of a tunnel leading into the dark depths of a mountain, another obvious subterranean underworld realm analogous to the mines of Moria. Finding his way through the darkened caves littered with corpses, Frodo is discovered by the monster that inhabits this underground lair. In the deep shadows inside the labyrinthine tunnels, Frodo is stalked and attacked by the monstrous spider, Shelob (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 27)—a figure that, in Jung’s view, might represent a mother-imago, the Goddess of Life and Death, the devouring Mother-Earth[17]—who stalks him in her underground web-strewn lair. Skeletons of her victims litter the dark caves, signaling the audience that the hero Frodo has yet again entered a symbolic “land of ghosts,” as he did previously during the nekyia descending into the tombs of Moria and later when he encountered the drowned corpses populating the Dead Marshes.

Fig.7. Shelob the monster-spider, after stinging and paralyzing Frodo, binds him like a mummy in her threads. Screenshot courtesy of New Line Cinema and Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

Shelob attacks Frodo in her dark underworld tunnels and stings him, injecting him with her poison (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 33). Then she binds him in a cocoon-like web to store away and devour as a later meal. The imagery portrays a paralyzed Frodo, unconscious and possibly dead, wrapped in a form-fitting straight jacket made of the monster’s sticky silken threads and tightly bound like a mummy in a tomb. The death imagery in this scene is vivid. Frodo appears helpless beyond repair, unconscious and wrapped in a cocoon-like prison of spun webbing like a mummified corpse. If he is not already dead, his death is imminent and seemingly unavoidable.

Fortunately, Sam arrives just in time to wound and defeat Shelob (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 33), but remains uncertain of the result. Sam gently unwraps the sticky-webbing from Frodo’s face—revealing his open-eyed lifeless gaze—and tries to wake the paralyzed hero. He realizes that Frodo is not asleep, but “dead.” At some distance, Sam mourns his dead friend as a gang of Orcs suddenly appears and discovers Frodo’s corpse. An Orc observes that “this fellow isn’t dead,” as nearby, Sam realizes his mistake. The Orcs carry Frodo, still wrapped in his mummy-web, off to a tower, most likely as their own dinner. Sam looks on helplessly from the shadows. Much later in the film, the main storyline continues as the previously mummified and paralyzed Frodo opens his eyes and awakens, surrounded by Orcs (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 45). The captive lies tightly bound as the cannibalistic Orcs fight among themselves, while Sam stealthily approaches the labyrinthine ruins of the Tower. At the fateful moment, again just in the nick of time, Sam appears, springs to the helpless Frodo’s defense with the sword Sting and slays an Orc in the act of murdering the captive Frodo. Yet again, Frodo returns to life from almost certain death.

Climactic Life and Death Crisis: The Ascent of Mt. Doom

The many symbolic deaths and rebirths of Frodo Baggins serve as a sort of initiatory rehearsal or preparation for the final climactic struggle that ends the epic saga. Following the battle at Minas Tirith and the triumph over Sauron’s army of Orcs at the Battle of Pelennor Fields, Gandalf warns Aragorn and the captains that “10,000 Orcs stand between Frodo and Mt. Doom” (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 46). Aragorn decides to launch a final assault at the Black Gate to distract Sauron, giving Frodo a better chance of success. The situation is bleak. As the main storyline continues (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 47), Sam tells Frodo: “I don’t think there will be a return journey, Mr. Frodo,” as he drinks the “few drops [of water] left.”

The central storyline continues as Frodo and Sam struggle to climb to the summit across an apocalyptic volcanic wasteland (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 49) as the wounded, exhausted, starving, and severely dehydrated Frodo stumbles and crawls, struggling to climb the upper slopes of Mt. Doom hand- over-hand. After seeing the One Eye, Frodo collapses, unconscious and clearly spent. He lies on the ground taking his last gasping breaths. Sam, cradling the dying Frodo in his arms, tries to comfort and inspire the fallen hero with memories of the peaceful Shire in springtime. After his narrow escape and miraculous rescue from Shelob, Frodo once again lies (apparently) dead in Sam’s arms. The stakes are high. If Frodo does not return to life yet again, the Quest ends and the world succumbs to Sauron’s apocalyptic designs. Having yet again escaped from the archetypal depths back to the “upper air,” Frodo barely revives once more, and the dual-heroes continue their strenuous ascent of Mt. Doom as Sam carries the exhausted hero on his back to the summit.

Fig. 8. Approaching the summit of Mt. Doom, Frodo Lies apparently dead—once more—in Sam’s arms. Screenshot courtesy of New Line Cinema and Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

At the entrance or threshold leading into the fiery mountain (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 51), Gollum unexpectedly reappears[18] and attacks Frodo again. In this scene, Gollum assumes the archetypal role of Campbell’s “threshold guardian,” an archetypal motif widely evidenced in Dante’s nekyia (Boyer, 2019). Sam wounds Gollum as Frodo stumbles into the mountain. Inside the active volcano, in yet another subterranean passage approaching the molten core, Frodo confronts Death for the last time in the climactic battle of the entire Quest. Gollum—who has miraculously sprung back to life after his fall into the pit—attacks Frodo again, this time at the edge of a narrow cliff overhanging the river of lava below. They struggle to the death. Gollum bites off Frodo’s Ring-finger, wounding him yet again, though not mortally this time, as the fate of Middle-earth hangs in the balance. Frodo and Gollum struggle for possession of the Ring as they teeter at the edge of the cliff overhanging the river of fire below. Then the adversaries lose their balance and fall to their apparent deaths. Gollum, holding the Ring, plunges to a fiery death in the blazing river of lava, but Frodo, still alive, dangles precariously over the molten flood. Sam arrives, once again just in time, and rescues Frodo by pulling him up to safety as the Ring sinks into the lava—the beginning of what Tolkien called a “eucastrophe” that continues to the story’s happy ending/s.

Fig. 9. Frodo suffers his final wound when Gollum bites off his finger in the climactic struggle to destroy the Ring in the fires of Mt. Doom. Screenshot courtesy of New Line Cinema and Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

At the final climax of the struggle for Middle-earth, the Ring returned to its source and destroyed at last, Sauron disintegrates (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 54), and a chain reaction destroys Mt. Doom and Barad-dur. Mt. Doom erupts with Frodo and Sam still trapped inside. They miraculously survive the final struggle with Gollum but are trapped hopelessly in the depths of the volcanic mountain as it erupts, climbing onto a rock surrounded by a rising river of molten fire (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 55). Sam’s prophetic warning to Frodo—that there might not be a return trip—seems close to fulfillment. But in a final close call, Frodo and Sam—all-but-dead—are miraculously (or eucastrophically) rescued by Gandalf, who flies to their rescue on the back of an eagle. Carried in the talons of giant eagles, Frodo and Sam make a final “upcoming” journey of ascent from the depths returning as successful heroes—like Aeneas, Dante, and countless others—to the “upper air.”

Fig. 10. Sam and Frodo await their death on a rock surrounded by rising lava in Mt. Doom. Screenshot courtesy of New Line Cinema and Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

The film’s lengthy denouement (Jackson, 2003, Chs. 56, 57, 58, and 59) is filled with iconography further representing Tolkien’s concept of eucastrophe—imagery representing a sudden reversal from doom to happy outcomes for the hero. Frodo awakens, as if reborn one final time, in a bed illumined by a numinous halo of sunlight, and the Fellowship is joyously reunited (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 56). Gandalf anoints and crowns Aragorn as king and, as the crowds rejoice, the restored King of Gondor is finally united with his Elf-Queen, Arwen (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 57), an image evoking the archetypal Jungian unio conjunctionis, unio mystica, or unio oppositorum known as the motif of the alchemical royal wedding or mystical wedding, written on extensively by Jung and represented in the conventional Hollywood happy ending where boy-gets-girl (Jung, 1992).

Then, the Fellowship ended, the quartet of Hobbits returns home to the peaceful and verdant greening Shire for feasting and celebration (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 58). A restless Frodo finishes writing his memoir of the adventure, The Lord of the Rings, a supplement to Bilbo’s memoir. Frodo realizes that there is truly, at least for him, “no going back.” “Some hurts go too deep,” Frodo narrates, “and have taken hold” (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 59). As Frodo told Gandalf in Tolkien’s original tale, he can never truly go home again. Frodo has been transformed by his journey and the many initiatory deaths and wounds suffered along the way. “There is no real going back,” Frodo explains in Tolkien’s original literature (Tolkien, 1994, p. 967). “Though I may come to the Shire, it will not seem the same; for I shall not be the same. I am wounded with knife, sting, and tooth, and a long burden.” At the ending of Jackson’s third film, Frodo accompanies Bilbo, Gandalf and the Elves as they board a ship sailing west to the Undying Lands known as the Grey Havens—the Elvish heaven-realm of Middle-earth. In the end, Frodo’s reward is immortality. His final triumph over Death leads to his divine apotheosis, represented by the iconographic imagery of his final journey as the ship leaves harbor and disappears in a spectacular aura of radiant light as the sun sets in the West (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 59). Frodo’s reward for his many deaths and rebirths is the Christ-like power demonstrated by countless mythical heroes to transcend Death itself.

In the final scene, Sam approaches his home in the Shire, greeted by his wife Rosie and their two small children amid the rich fertility of his garden in full bloom. The eucastrophic iconography of Sam’s final scene echoes both the royal alchemical wedding of King Aragorn and Queen Arwen and the earlier scene of the Hobbits returning home to the fertile springtime nature of the bucolic Shire that, in stark contrast to the sterile dystopian wasteland of the Quest, suggests the cyclical restoration of Nature’s fertility and regenerative growth. The cycle of Nature—going from fertility to infertility and back again, a metaphor of the Quest itself—is now complete. Sam, the gardener-hero, returns to a home resplendent with the rich bloom of his greening garden. As Sam and family enter their home and close the door, the camera focuses on the circular sun-like portal of the door, illumined by dappled sunlight, a mandala-like image that fittingly closes the story: the circular golden door an apt symbol of completion—the ever-renewed fertility of the land and people, and the circle of life portrayed in the hero’s completed adventure, “There and Back Again.”

Concluding Remarks

In this study, evidence of Tolkien’s use of pre-existing symbolic death and rebirth imagery is discussed as represented in both the narrative text (i.e., narration, dialogue) and pictorial iconographic imagery in Jackson’s film. Tolkien’s literary transformation of symbolic death and rebirth imagery—Jung’s rebirth archetype—is examined in the creation of his mythopoeic literature, interpreted through the cinematic adaptation of Tolkien’s novels by filmmaker Jackson. The symbolic rebirths and transformations of Frodo Baggins are, furthermore, echoed in a wide array of other major and minor characters in both the original literature and Jackson’s films. These figures include most notably Aragorn and Gandalf (and the central villain, Sauron), as well as an array of supporting characters, including Sam, Faramir, Theoden, and Gollum. This initial paper also discusses, albeit briefly, cyclical rebirth imagery evident at the heart of Tolkien’s and Jackson’s narratives, represented in the archetypal topographical and directional symbolism of the Quest’s background settings and in the overall narrative arc of the trilogy as a whole—a narrative structural arc of descent and ascent that Northrop Frye calls the “great code of art,” an observation he based largely on Greek myths and the Bible (Frye, 1990).

Whether Tolkien deliberately chose this age-old transformational symbolism as a matter of conscious narrative craft and a great artist’s instinct for the conventions of mythic storytelling—that is, deliberately borrowed the imagery as a convention of storytelling modeled on pre-existing myths and mythopoeic literature—or whether the imagery spontaneously and unconsciously arose from what Jung calls the creative or collective unconscious—remains uncertain and a proper subject for further research. Evidence suggests the latter explanation. Tolkien, after all, described his creative process as that of being an instrument, that is, “sub-creator,” rather than a creator. According to Jung, archetypal imagery often appears spontaneously and unconsciously in the imagination of artists in the throes of creative expression, that is, under the “spell of the Muse” (Jung, 1971, pp. 65-83 and pp. 84-105).

What is certain is that this modern mythopoeic legend-maker was at least aware of the archetypal nature of his story, even if after the fact, and of the apparent connection between his story’s extraordinary appeal and the use of archetypal imagery. A recorded conversation among the Inklings also suggests Tolkien’s tacit assent to Jung’s theory of creative process was also relevant to the creation of his fiction. According to eyewitness Humphrey Carpenter, the issue was raised in a discussion among the Inklings at which Tolkien himself was present. One of the Inklings, Mr. Havard, began the conversation thread saying: “I don’t know how you think of these things.”

In reply:

How does any author think of anything?’ answers Jack Lewis, quick as usual to turn the particular to the general. ‘I don’t think that conscious invention plays a very great part in it. For example, I find that in many respects I can’t direct my imagination: I can only follow the lead it gives me.’ Havard asks: ‘What do you suppose is the explanation, or the significance? I imagine Jung would ascribe it to the collective unconscious, whose dictates you are being obliged to follow.’ ‘Maybe,’ Lewis says. ‘Jung’s archetypes do seem to explain it, though I’d have thought Plato’s would do just as well. And isn’t Toilers [Tolkien] saying the same thing in another way when he tells us that Man is merely the sub-creator and that all stories originate with God?’ Tolkien grunts in agreement. (Carpenter, 1979, p. 138)

In this simple, gruff gesture of affirmation, Tolkien tacitly acknowledged the relevance of Jung’s theory of the archetypes to his narrative art and that his artistic creation of mythopoeic images in the creation of LotR might therefore serve as a locus of psychological meaning both in terms of the imagery of his creation and its process of creation.

Conclusion

Jung’s rebirth archetype—the archetype of transformation—is evident in the symbolic initiatory deaths and rebirths experienced by the hero and main character (or protagonist) of Tolkien’s tale, the mythic hero-redeemer, Frodo Baggins. Through a series of symbolic initiatory deaths, Frodo is transformed from a humble and fearful young Hobbit of the Shire into the courageous and heroic Ring-bearer of the Quest and eventual savior-redeemer of Middle-earth. These initiations of Frodo function as the underlying symbolic grammar of iconographic imagery that drives the central plot of Jackson’s condensed cinematic adaptation of the epic original literature. This study contributes to the growing literature on the Jungian rebirth archetype and, more generally, to the growing influence of Jungian-informed depth-psychological perspectives in the humanities (Rowland, 2010) and their interdisciplinary relevance for understanding and interpreting mythopoetic imagery in the narrative arts.

Endnotes

[1] Proper titles for Tolkien’s and Jackson’s Lord of the Rings will be abbreviated throughout the essay, as indicated.

[2]For purposes of this essay, the standard theatrical versions of Jackson’s films appear in DVD format. Titles will be abbreviated as indicated here. Unless indicated otherwise, in-text citations will cite Jackson as author, the date of the film release, and the relevant DVD chapter).

[3]According to archeologist Marija Gimbutas, death-rebirth imagery appears as early as the Upper Paleolithic in the matriarchal Goddess religions predating Old Europe. Marija Gimbutas, Language of the Goddess, 1991.

[4] Frodo, Aragorn/Strider, and Gandalf are all “parentless” mythical heroes. Though Tolkien was himself an orphan, the orphaned origin myths of the hero are collective and ubiquitous, for example, the Finnish hero Kullervo in the Kalevala saga, the retelling of which is the subject of Tolkien’s first prose writing. Also see Boyer, “Introduction to the Mythic Orphan: Archetypal Origins of the Hero in Myth, Literature, and Film,” 2012.

[5]For details, see my literature review, “The Rebirth Archetype: A Review of the Literature,” 2018.

[6]A current study by this author has documented the “rebirth archetype” myth-motif in more than 500 (and counting) films and cable TV series, including many of the most commercially successful blockbusters ever made (e.g., Lord of the Rings, the James Bond and Harry Potter film franchises, the Game of Thrones TV franchise, ad infinitum).

[7]For purposes of consistency, I adopt the capitalized spelling of the term “Hobbit,” based on Tolkien’s original language and Jackson’s cinematic English sub-titles.

[8] The likely source of this quote is the poem Wind-Wafted Wild Flowers by poet Murial Strode, published in 1903 in the journal The Open Court. Quoteinvestigator.com/2014/06/19/new-path/. Accessed 7 December 2018.

[10]Night-sea journey imagery also explicitly albeit briefly appears in this story (Jackson, 2001, Ch. 11). The scene occurs during the initial late-night pursuit through the woods as Frodo and his companions barely escape the Nazgul by boarding a skiff and journeying downriver at night to Brandywine Crossing.

[11]Whether Tolkien deliberately borrowed Dante’s nekyia imagery from The Inferno, borrowed by Dante from Virgil’s The Aeneid, is a question for a different study. That Tolkien was intimately familiar with Dante’s mythopoetics is, however, not an open question. See Jacopo della Quercia, “‘The Nobile Castello’ of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth.”

[12]Aragorn’s death and rebirth initiations, as well as those of Gandalf and a host of major and minor supporting characters, will be discussed in Part II of this study. For a second more dramatic example of Aragorn’s transformations see his apparent death and rebirth in Jackson, 2002, Chs. 26 and 29.

[13]This brevity perhaps results from the practical need to focus on the dramatically more intense and classic death of Gandalf that occurs in Moria (Jackson, 2001, Ch. 30) soon thereafter and the Wizard’s subsequent rebirth or resurrection as “Gandalf the White” (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 13), a topic to which we will return in Part II.

[14]The landscape approaching Mordor is described by Boromir as a “wasteland.” Journey into the depths of a wasteland is yet another route into the psychic landscape, familiar to readers of medieval Romance in the tales of the knight errant Parsifal and the wounded Grail King. Underlying that image is another ancient metaphor of death-rebirth pictured using nature metaphors, the cycles of the hero-king’s sterility and fertility-power magically linked to the renewed fertility of the land itself. See James Frazer, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, 1963.

[15]The poet Virgil poetically illustrates Campbell’s “downgoing and upcoming” trajectory of hero descent and ascent in The Aeneid (p. 186), a pre-existing story arc closely imitated by Dante, in a passage where the hero is warned by the Sibyl of Cumae as they gaze into the depths of the underworld: “Descent to the underworld is easy./Night and day the gates of shadowy Death stand open wide,/But to retrace your steps, to climb back up to the upper air—/There the struggle, there the labor lies.”

[16]Once again the iconography amplifies the journey to the “land of ghosts” characteristic of Jung’s nekyia. See RotK, “Aragorn Takes the Paths of the Dead” (Ch. 23), “Dwimorberg – The Haunted Mountain” (Ch. 25), and “The King of the Dead” (Ch. 27).

[17]According to both Campbell (1973) and Eliade (1958), archetypal heroes are often devoured by monsters in one form or another. This is yet another form that depth imagery takes of an initiatory kind, widely evident in ancient mythologies and initiation rites. Also see Boyer, “The Rebirth Archetype in Fairy Tales,” (Spring 2017) discussing the rebirth imagery in the fairy tale of Little Red Cap (Little Red Riding Hood), devoured by a monstrous wolf and Boyer, “The Sign of Jonah: Initiatory Symbolism in the Old Testament,” (Fall 2017) which discusses similar symbolism in the Old Testament myth of Jonah and the Whale. With slight variation in Tolkien’s tale, the monsters only attempt to devour Frodo, while the overall arc of the death and rebirth cycle of the hero remains.

[18]The Gollum fell into an underground abyss to his presumptive death during the mortal struggle with Frodo earlier in Shelob’s caves (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 29). Smeagol reappears alive—that is, symbolically reborn—in the climax of the film (Jackson, 2003, Ch. 53).

References

Alighieri, D. 2002. The Inferno (R. Hollander and J. Hollander, Trans.). New York, NY: Anchor.

Aristotle. 1997. Poetics (M. Heath, Trans.). New York, NY: Penquin.

Beowulf: A new verse translation (S. Heaney, Trans.). 2000. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Boyer, R. L. 2010. Key archetypes in Tristan and Isolde. Unpublished manuscript. Department of Psychology, Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park. http://www.academia.edu/622341/Key_Archetypes_in_the_Celtic_Myth_of_Tristan_and_Isolde_A_Brief_Introduction.

Boyer, R. L. 2010. Nature as a mirror of psyche: On the theme of eternal return. Unpublished manuscript. Department of Psychology, Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, 2010. http://www.academia.edu/622322/Nature_as_a_Mirror_of_Psyche_On_the_Theme_of_Eternal_Return_Observations_from_a_ Nature_Journal.

Presenter, Boyer, R. L. (2012 Summer). Introduction to the Mythic Orphan: Archetypal Origins of the Hero in Mythology, Literature, and Film. Presented at the 1st Symposium for the Study of Myth, Pacific Graduate Institution, Santa Barbara.

Boyer, R. L. (Summer 2014). Entering the other world of Oz: The threshold passage of Dorothy Gale. Coreopsis: Journal of Myth and Theater, 3(2). http://www.academia.edu/7574495/Entering_the_Other_World_of_Oz_The_Threshold_Passage_of_Dorothy_Gale.

Boyer, R. L. (2014). The Gospel as transformative myth: Individuation imagery in DeMille’s King of Kings. Unpublished manuscript. Art and Religion Department, Graduate Theological Union and University of California, Berkeley.

Boyer, R. L. (2015a). Mythopoeic imagery in Blake’s art (part II): Death-rebirth symbolism in image and text. Unpublished manuscript. Art and Religion Department, Graduate Theological Union and University of California, Berkeley, May.

Presenter, Boyer, R. L. (2015b, June). To die, and be reborn: The death-rebirth archetype in myth & rite, literature & film. Presented at the International Conference of the International Association of Jungian Studies, Arizona State University, Phoenix.

Boyer, R. L. (Spring 2017). The rebirth archetype in fairy tales: A study of Fitcher’s Bird and Little Red Cap. Coreopsis: Journal of Myth and Theater, 6(1). http://www.societyforritualarts.com/coreopsis/spring-2017-issue/the-rebirth-archetype-in-fairy-tales/

Boyer, R. L. (Fall 2017). The sign of Jonah: Initiatory symbolism in biblical mythopoetics. Coreopsis: Journal of Myth and Theater, 6(2). http://www.societyforritualarts.com/coreopsis/Autumn-2017-issue/portfolio-item/the-sign-of-jonah-initiatory-symbolism-in-biblical-mythopoetics/.

Boyer, R. L. 2018. The rebirth archetype: A review of the literature. Unpublished manuscript. Art and Religion Department, Graduate Theological Union and University of California, Berkeley, Fall.

Boyer, R. L. (Spring 2020). Descensus ad inferos: Dante’s mythic nekyia journey in The Inferno. Coreopsis: Journal of Myth and Theater, 8(1). http://societyforritualarts.com/coreopsis/spring-2020-issue/descensus-ad-inferos/

Campbell, J. 1973. The hero with a thousand faces. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Campbell, J. 1990. The flight of the wild gander: Explorations in the mythological dimensions of fairy tales, legends and symbols. New York, NY: HarperPerennial.

Carpenter, H. 1979. The Inklings. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Eliade, M. 1958. Rites and symbols of initiation: The mysteries of death and rebirth (W.R. Trask, Trans.). New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Eliade, M. 1974. Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy (W.R. Trask, Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Frazer, J. 1963. The golden bough: A study in magic and religion (Abr. ed.). New York, NY: Collier.

Frye, N. 1963. Fables of identity: Studies in poetic mythology. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Frye, N. 1990. Anatomy of criticism: Four essays. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Frye, N. 1990. The great code: The Bible and literature. New York, NY: Penquin Books.

Gebser, J. 1986. The ever-present origin: Foundations of the aperspectival world and Part two: Manifestations of the aperspectival World (N. Barstad with A. Mickunas, Ed. & Trans.). 1st ed. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Gennep, A. van. 1975. The rites of passage (M.B. Vizedom and G.L. Caffee, Trans.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Gimbutas, M. 1991. The language of the Goddess. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Hammond, W.G. & C. Scull. 1995. J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist & illustrator. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Henderson, J. L. & M. Oakes. 1963. The wisdom of the serpent: The myths of death, rebirth, and resurrection. New York, NY: George Braziller.

Inanna: Queen of heaven and earth: Her stories and hymns from Sumer (D. Wolkstein and N. Kramer, Trans.). New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1983.

Jackson, P. (Director). 2001. The lord of the rings: Fellowship of the ring [motion picture] USA: New Line Cinema.

Jackson, P. (Director). 2002. The lord of the rings: The two towers [motion picture]. USA: New Line Cinema.

Jackson, P. (Director). 2003. The lord of the rings: Return of the king [motion picture]. USA: New Line Cinema.

Jung, C. G. 1971. On the relation of analytical psychology to poetry, and Psychology and literature. In Herbert Read, et al, (Series Eds.), The Spirit in Man, Art, and Literature (R.F.C. Hull, Trans.), pp. 65-83 & pp. 84-105. CW, Vo. 15. 20 vols. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. 1973. Four archetypes: Mother/rebirth/spirit/trickster (R.F.C. Hull, Trans.). Extracted from The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Vol. 9, pt. 1 of CW, edited by Herbert Read et al, series editors. 20 vols. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. 1991. Psychology of the Unconscious: A Study of the Transformations and Symbolisms of the Libido (B. Hinkle, Trans.). Supplementary Vol. B, CW, edited by Herbert Read, et al, series editors. 20 vols. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. 1992. The Psychology of the Transference (R.F.C. Hull, Trans.). CW, Vol. 16, edited by Herbert Read, et al, series editors. 20 vols. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mythopoeic Society, “Mythopoeic Literature.” http: www.mythsoc.org/about.htm. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

Quercia, J. della. “‘The Nobile Castello’ of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth: Inferno 4.106-108,” December 2013. http://www.princeton.edu/-dante/ebdsa/quercia121113.html. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

Rank, O. 1964. The myth of the birth of the hero and other writings (P. Freund, Trans.). New York, NY: Vintage.

Roberts-Donaldson. “Gospel of Nicodemus: The Descent of Christ into Hell.” n.d. http://www.earlychristianwritings:com/actspilate.html. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

Rowland, S. 2010. C.G. Jung in the Humanities: Taking the Soul’s Path. New Orleans, LA: Spring.

Tolkien, J. R. R. 1988. Mythopoeia, Tree and Leaf. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Tolkien, J. R. R. 1994. The lord of the rings. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

Turner, V. 1992. Death and the dead in the pilgrimage process, and Variations on a theme of liminality (1962-1978). In. E. Turner (Ed.), Blazing the Trail: Way Marks in the Exploration of Symbols (pp. 29-47 & pp. 48-65). Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Virgil. (1988. The aeneid of Virgil (A. Mendelbaum, Trans.). New York, NY: Bantam.

Weston, J. 1957. From ritual to romance. New York, NY: Doubleday Anchor.

List of Illustrations

Figure 1: Entering Mirkwood by Ted Naismith. Illustration.

Figure 2. Early in the adventure, Frodo is stabbed and seriously wounded by the Witch-king’s poisoned blade. Screenshot.

Figure 3. Original illustration of the Door of Durin by J. R. R. Tolkien. Illustration.

Figure 4. In this classical hero nekyia, or journey of descent, Virgil guides Dante into the subterranean depths of Hades. Illustration.

Figure 5. Frodo lies apparently dead from the wound inflicted by a giant Cave Troll’s spear. Screenshot.

Figure 6. Frodo charmed by the Death-spell in the Dead Marshes. Screenshot.

Figure 7. Shelob the monster-spider, after stinging and paralyzing Frodo, binds him like a mummy in her threads. Screenshot.

Figure 8. Approaching the summit of Mt. Doom, Frodo lies apparently dead—once more—in Sam’s arms. Screenshot.

Figure 9. Frodo suffers his final wound when Gollum bites off his finger in the climactic struggle to destroy the Ring. Screenshot.

Figure 10. Sam and Frodo await their death on a rock surrounded by rising lava in Mt. Doom. Screenshot.

Ronald L. Boyer is a scholar, teacher, and award-winning poet, fiction author, and screenwriter. He holds an MA in Depth Psychology from Sonoma State University and is a graduate of the Professional Program in Screenwriting at UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television.

Ronald L. Boyer is a scholar, teacher, and award-winning poet, fiction author, and screenwriter. He holds an MA in Depth Psychology from Sonoma State University and is a graduate of the Professional Program in Screenwriting at UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television.

Ron is currently a doctoral student in Art and Religion at the Graduate Theological Union and UC Berkeley. His scholarly research emphasizes Jungian archetypal theory applied to mythology, literature, and film, with a concentration on mythopoeic imagery in the art of Dante Alighieri, William Blake, and J.R.R. Tolkien. He is an associate editor/reviewer for the peer-reviewed journal, the Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology, and a referee and regular contributor to the peer-reviewed journal, Coreopsis: Journal of Myth and Theater. Ron has presented academic papers at the first Symposium for the Study of Myth at Pacifica Graduate Institution, the International Conference for the International Association for Jungian Studies at Arizona State University, and other forums.

Ron is a two-time Jefferson Scholar to the Santa Barbara Writers Conference and two-time award-winner for fiction from the John E. Profant Foundation for the Arts, including the prestigious McGwire Family Award for Literature. His poetry has been featured in the scholarly e-zine of the Jungian depth psychology community, Depth Insights: Seeing the World with Soul, Mythic Passages: A Magazine of the Imagination, Mythic Circle, the literary magazine of the Mythopoeic Society, and many other publications.

His writings can be accessed at his scholarly website, www.gtu.academia.edu/RonaldLBoyer/papers