An argument can be made that Dante’s Comedy is an example, written in the late Middle Ages, of mythopoeic literature as a symbolic hero quest myth (Campbell) and nekyia journey of descent (Jung).

Abstract

Keywords: archetypes, Carl G. Jung, comparative mythology, Dante, depth psychology, Divine Comedy, iconography, Joseph Campbell, literature, mythology, nekyia

The night sea journey is a kind of descensus ad inferos, a descent into Hades, and a journey to the land of ghosts somewhere beyond this world, beyond consciousness, hence an immersion in the unconscious.

—Carl Gustav Jung

Dante’s Divine Comedy (Ciardi, 1970) is an early masterpiece of world literature, an enduring perhaps immortal literary classic whose stature rivals ancient classics such as Homer’s Odyssey (Lattimore, 1967) and Virgil’s Aeneid (Fagles, 2010)—the work upon which The Comedy is deliberately modeled. Dante’s Comedy is also an early prototype of the modern literary genre referred to as mythopoeic (or mythopoetic) literature, as well as an example of what might be called archetypal literature, a general category of narrative transcending specific literary and cinematic genres, for instance, the mythological and literary expressions of the hero quest myth whose symbolic structure was delineated by mythologist Joseph Campbell (1949/1973).

An argument can be made that Dante’s Comedy is an example, written in the late Middle Ages, of mythopoeic literature as a symbolic hero quest myth (Campbell) and nekyia journey of descent (Jung). Mythopoeic literature[1] has been associated with the writings of J.R.R. Tolkien and the Inklings, his distinguished literary colleagues at Oxford, as well as the specific literary genres of fantasy and speculative fiction in which Tolkien and C.S. Lewis are acknowledged pioneers. These authors made use of pre-existing mythological elements in creating fictional narrative worlds, literary myths evoking an obviously mythic quality and making significant use of conventional features of myth-making. In short, authors of mythopoeic narratives utilize archetypal symbols and structure—in the forms of recurring motifs and images—in the creation of their tales. Dante uses many such mythic images in creating the imaginal realm of The Inferno, which might also be understood as a prototype in the genre of literary horror, a sub-category of speculative and fantasy fiction. For example, much of Dante’s subject matter in The Inferno consists of the nearly indescribable horrors of Hell, exhaustively and terrifyingly catalogued by the author. This fictional portrayal influenced centuries of popular Christianity’s literalistic conceptions of Hell reaching down to the present day. On the level of narrative craft, Dante uses the first person point of view of story narration to powerful effect, a technique of writing craft uniquely suited for horror tales in which the author, as fictitious narrator of a tale, describes fantastic realities as a form of fictional memoir, thus granting the credibility of a first- person witness account of the uncanny events related in the tale—a technique used by masters of horror from G. du Maupassant (e.g., The Horla, 1989) to H.P. Lovecraft.

Mythopoetics and Jungian Archetypal Theory

These roots of mythopoeic storytelling are evident in the symbolic forms and structural elements of storytelling narrative, whether mythic, literary, or cinematic. To speak metaphorically, the language of mythic narrative is constructed of an archetypal alphabet consisting of symbolic imagery, as the analyst Carl G. Jung[2] discovered, the building blocks of mythopoeic forms. Mythic language is a language rich in poetic, symbolic forms, that is, the imagery of metaphor and simile. For such reasons, archetypal literary theorist and myth-critic Northrop Frye (1963) viewed the whole of world literature as “displaced mythology” (pp. 21-38). Jung posited a collective unconscious, a timeless and universal psyche, as the source of these images appearing in myth, literature, and other forms. The unconscious psyche, Jung suggested, possesses the capacity to represent “affect laden situations” poetically and symbolically in a universal “picture language” of “myth-motifs” that, following Plato and others, he called archetypes. Archetypes, rooted in the instincts and human biology, are presumably universal, according to Jung, and transcend time and space. In short, these primordial images appear everywhere, in all times and places, with analogous imagery found in the creation myths and hero myths of the world, folklore and fairytale, the arts and religion, as well as in the dreams and imaginative fantasies of contemporary individuals, including psychotics and creative artists (like Dante).

Jung noticed that the same images he observed in myth, fairytales, and visual arts appeared in his own dreams and fantasies, as well as those of his patients. This observation of analogous imagery appearing repeatedly and spontaneously in distant times and places too historically and geographically remote to have been disseminated by cultural diffusion, led to Jung’s theory of the archetypes. His observations of repetitive image-patterns eventually evolved into Jung’s interpretive analytical methodology called amplification or analogical thinking, which consisted chiefly of noticing patterns of analogous imagery wherever they appear, used as tools for understanding unconscious psychic processes in his patients. Jung defined these archetypal primordial images or symbolic myth-motifs as “forms or images of a collective nature which occur practically all over the earth as constituents of myths and at the same time as autochthonous, individual products of unconscious origin” (Jung, 1958, pp. 83–84).

These recurring primordial images are the presumptively universal elements of a symbolic alphabet from which the language of myth evolves in derivative storytelling forms, including literary and film narratives. The images are like letters forming, collectively, the symbolic alphabet from which the language of mythopoeic narrative is constructed—including, as will be demonstrated shortly, Dante’s Comedy. Jung’s primordial images or myth-motifs function as the fundamental metaphorical building blocks of myth, familiar to storytellers, myth-makers, and their audiences since primordial pasts, when shamans of indigenous tribal peoples everywhere invented metaphors for describing otherwise inexpressible experiential realities, beginning with the cosmogonies and origin myths passed down through oral traditions and sacred rites since the beginning-less past.

In this study, a textual analysis and archetypal interpretation of Dante’s journey in The Inferno is approached through the interdisciplinary theoretical and methodological framework created by Jung and mythologist Joseph Campbell, emphasizing the mythopoeic nature of The Comedy evidenced in its root-meaning of primordial, archetypal transformational imagery of descent-return as initiatory death-rebirth (Boyer, 2014b; Boyer, 2017a; Boyer 2017b). This study focuses on structural imagery of an archetypal-mythopoeic nature in Dante’s narrative, interpreted as symbolic of presumptively universal unconscious psychological transformative processes (Jung’s nekyia or journey of symbolic descent into the depths and Land of the Dead), rather than on features of the story that are merely local and historical, that is, its specifically medieval European Christianity-based interpretive framework.

The unconscious psyche, Jung suggested, possesses the capacity to represent “affect laden situations” poetically and symbolically in a universal “picture language” of “myth-motifs” that, following Plato and others, he called archetypes.

Depth Imagery in Dante’s Journey of Descent

Findings and Discussion

Dante utilized widely recurring visual and narrative metaphors and motifs in describing his journey into Hell, imagery found in abundance in the world’s mythology and ritual narratives common to pre-literate indigenous societies everywhere. Dante crafted his uniquely historical Christian theological interpretation, and political critique of the Church and various powers of his day, on a mythic symbolic superstructure of pagan imagery that is undoubtedly primordial and presumably universal in origin. This mythic symbolism is widely evident in Dante’s trilogy, beginning with the conventional topographical imagery of the initial stage of the hero journey, the archetypal journey of descent into the depths.

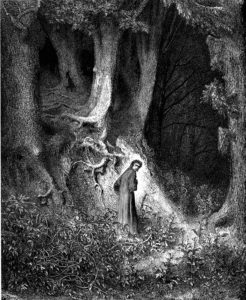

Dante’s hero descent into the depths of a dusky wood. “Stopped mid-motion in the middle/Of what we call our life, I looked up and saw no sky—/Only a dense cage of leaf, tree, and twig. I was lost” (Bang, 2012, p. 15).[3] These opening lines of Dante’s Inferno, the first book in his epic trilogy, The Divine Comedy, are some of the most memorable lines in all of world literature. Readers meet the character “Dante,” the narrative hero of The Comedy, already lost in the dark depths of his unconscious life, represented by the author Dante using the timeless metaphorical myth-motif of a dense, sunless forest. “It is difficult to describe a forest:/Savage, arduous, extreme in its extremity” (p. 154). In Dante’s story, this primitive “dusky wood” is the shadowy archetypal landscape through which the hero passes fully “into the depths of the abyss” (p. 154).

Fig. 1. Dante initiates his journey by entering the symbolic depths of a dark, “dusky” wood. Illustration by Gustave Dore, published 1861.

This image of a primeval forest is a typical and widely distributed topographical symbol evident in Indo-European myths, for example, those of the Celts. These ancient narratives depict the stories of the gods, kings, and heroes of mythic Ireland, Britain, and beyond. For instance, semi-divine Celtic heroes like Pwyll (Ford, 1977, pp. 35-56) undertook perilous adventures in the liminal other world, frequently described as hunting expeditions into a densely forested wilderness. This ancient imagery reappears in medieval Celtic Romance literature, where King Arthur, Parsifal, and the knights of the Grail quest typically initiate their quests by entering a pathless path into a deep forest, one of Campbell’s favorite depth motifs.

This myth-motif is also common to Indo-European folk and fairytales, where child-heroes from Hansel and Gretel to Red Riding Hood (Boyer, 2017a) venture into the depths of enchanted forests, where they typically encounter monstrous supernatural figures (e.g., wolves, witches, etc.) who threaten to devour them. A wonderfully illustrative example of the hero descent into the depths by way of forest appears in the “modernized fairytale” by L. Frank Baum (1900), The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, where Dorothy Gale’s nekyia journey of descent in Oz is portrayed as a series of descents into increasingly dark and frightening woods. In the deepest, darkest forest, the heroine enters the symbolic Land of the Dead in the form of a Haunted Forest where the Cowardly Lion declares: “I do believe in spooks, I do believe in spooks.” In the depths of the Haunted Forest—a symbolic Jungian “land of ghosts”—Dorothy is abducted to Hades-like depths, imagined as a desolate shadowy wasteland ,where she is imprisoned in the castle of her supernatural nemesis, the Queen of the Underworld represented as the Wicked Witch of the West.

When readers first meet the character Dante in the dusky forest, the hero is already situated in archetypal landscape, a dark and deep otherworldly wilderness through which he must find his way back to the daylight world. Like Dorothy Gale and the questing knights of the Grail, Dante moves through this thickly forested landscape, analogous to the journeys of countless mythic heroes before and after. The image of a dense, dark forest where the hero is lost functions as a powerful visual metaphor for the descent into Jung’s collective unconscious, the primordial realm of archetypes. The heroes of countless mythic narratives personify this encounter with the unknown, described as a symbolic transformative journey across an archetypal magical landscape in an “otherworld” in some form. As archetypal psychologist James Hillman (1979, p. 51) suggested, they move from material to psychical space, to the “land of soul.” As a topographical metaphor, the deep dark forest motif can be interpreted consistently, as Campbell suggested, as an image of psychic depths. From the viewpoint of Jung and scholars influenced by his work, including Campbell, this encounter with unknown powers in the dark depths of the forest may be understood as a reflection, in the dark mirror of art, of every individual’s mysterious inner journeys into the unknown, as metaphors for unconscious, deep psychic processes of transformation described as the process of individuation, Jung’s term for what he viewed as the ultimate aim of human life. For both Jung and Campbell, this journey is interpreted as a perilous road of trials. As he prepared to follow Virgil on this descending path, Dante appropriately referred to the adventure ahead as a trial, a “difficult task” (Bang, 2012, p. 25).

Significantly, in terms of both Jung’s and Campbell’s interpretations, Dante encounters the dead poet Virgil early in his journey into the depths. Virgil tells the hero that he’ll “play the part of … guide” (Bang, 2012, p. 18). Virgil’s shade becomes Dante’s guide and protector in the netherworld of The Inferno, functioning as psychopomp, Dante’s guide through the underworld, as the Sibyl of Cumae did for the hero Aeneas in Virgil’s Aeneid (a.d./2006). Virgil also functions in Dante’s narrative as the “supernatural ally” Campbell typically observed in archetypal hero quests. “The first encounter of the hero-journey is with a protective figure,” said Campbell (1949/1973, p. 69). Virgil, as this protective guide, personifies the “benign protecting power of destiny” (p. 71).[4] In Jungian terms, Virgil represents the archetypal Wise Old Man, a personification of the Self, a figure Jung considered a major archetype.

Virgil, as Wise Old Man in Dante’s poetic narrative, is Dante’s teacher and mentor on the journey, until he leaves Dante with Beatrice in The Purgatorio (Ciardi, 1970), Dante’s feminine supernatural ally and protective guide in the tale. In Jung’s terms, this larger-than-life anima figure in Dante’s tale looms in the narrative background, beckoning and inspiring—in the form of poetic Muse—Dante’s journey as both author and character. Such figures, which personify the Self, the anima, etc., are, according to Jung, among the key archetypal characters found in myths throughout the world—along with the archetypal Shadow, in this tale represented by a multitude of dark spirits and damned figures the hero meets on his journey, including Satan himself. These larger-than-life figures are encountered, Jung added, in the transformative imagery of the individuation process, a psychological process analogous to journeys of heroic descent and symbolically depicted in a variety of ways in the fairytales and myths of the world.

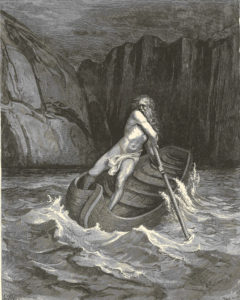

Fig. 2. Upon entrance to the underworld, Dante and Virgil begin a night-sea journey when the boatman of the underworld, Charon, approaches to take them to the Other Shore. Illustration by Gustave Dore, published 1861.

Dante’s descent pictured as Jung’s night-sea journey. Both Freud and Jung observed a phenomenon they refer to as an over-determination of symbols in dreams, creative fantasies, and the narrative representations of myth. It is as if the unconscious, the presumed source of creativity and symbolic language in depth psychology, reinforces the imagery so that multiple symbolic images in the content of a given dream or work of art possess complementary and analogous meanings that reinforce and amplify its symbolic message. The hero journey into the depths of the forest, a common myth-motif in folk and fairytales and myths the world over, is echoed in the analogous metaphorical imagery of what Jung calls the “night sea journey,” a journey into the dark night and depths of a watery abyss. As Jung’s opening epigraph suggests, the “night sea journey is a kind of descensus ad inferos, a descent into Hades, and a journey to the land of ghosts somewhere beyond this world, beyond consciousness, hence an immersion in the unconscious” (Jung, 1946/1992, pp. 83–84).

Dante’s wedding of the myth-motifs of the hero quest in the depths of forests with Jung’s night sea journey and the analogous myth-motif of subterranean descent into Hades—“the land of ghosts … beyond this world”—is a rare example in literary mythology that forcefully illustrates the nearly identical motifs of Campbell’s heroic wilderness landscape and Jung’s thesis of symbolic identity between the myth-motifs of descent into the depths of a dark watery abyss and the descent into the subterranean underworld (i.e., Hades or Hell).

Many heroes take this night-sea journey into the depths. For one example, the Celtic hero Tristan undertakes a night-sea journey to Ireland in a boat lacking oars or sails. There he undergoes a miraculous rebirth from a magic wound, a wound that does not heal, with the help of his mortal enemy, Isolde, the sorceress queen of Ireland (see Bedier, 1945; Boyer, 2011). Another of the great mythic heroes whose journey takes the form of a water journey into the depths of the night sea is the Greek hero Odysseus (the Roman, Ulysses), the protagonist of Homer’s Odyssey, the epic story of arguably the longest sea voyage depicted in world literature. Significantly, Dante meets Ulysses in the depths of Hades-Hell, where Ulysses narrates a part of his journey, evoking imagery of his own night-sea adventure in the depths. “Since we’d begun our Jules Verne journey,” says Ulysses in Bangs’ poetic modern translation (2012, pp. 248-251), alluding to the modern literary version of a submarine journey in the depths authored by Verne in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

One of the most illustrative mythic portrayals of the nekyia as night-sea journey is the ancient tale of the Sumerian hero Gilgamesh, “an old story/but one that can still be told/About a man who loved/And lost a friend to death/And learned he lacked the power/To bring him back to life” (Mason, 1972, p. 11). When Gilgamesh’s best friend, the wild man Enkidu, dies, the archetypal hero descends into the Sumerian underworld. There he undergoes a perilous night-sea journey through the underworld to find the secret of immortality that might bring Enkidu back to life. Ferried across the dark “sea of death” in the boat of Urshanabi, the Sumerian Charon, Gilgamesh quests to obtain this secret power of rebirth from the immortal Utnapishtim, an archetypal blind seer figure (like the Greek, Tiresias) who lives on the other shore of the underworld. His hero quest fails when a mythical serpent eats the plant of immortality, acquiring miraculous powers symbolically portrayed as the serpent’s ability to periodically slough its skin and be continuously reborn (p. 86). This myth features an amplification of death-rebirth imagery observable in both the structural topographical landscape or background setting (i.e., night-sea, underworld) of the tale, and in the story’s detailed foreground imagery as well (i.e., the serpent’s power of cyclical rebirth bestowed by the plant of immortality).

In The Inferno, the hero Dante, accompanied by his guide, the shade of Virgil, begins the next stage of his adventure of descent, evoking Gilgamesh, with this archetypal imagery as its setting. No sooner do Virgil and Dante pass into the “City of Woe,” the “Grave Cave” of “everlasting sadness,” the place of “no hope”—the “place where you’d see the wretched dead” (Bang, 2012, p. 33)—than their night-sea journey begins. “Then we crossed over from where we’d been/Into the inner sanctum that houses hidden things.” There they observe a huge crowd of shades on the banks of a wide river, the river Acheron (p. 35)—that underworld body of water that acts as a boundary between limbo and the realm of Hades-Hell proper. In Dante’s tale, Acheron—“Sad Acheron, of sorrow, black and deep” (Bang, 2012, p. 138; Milton, 1982, p. 85)—is a type of liminal threshold the hero must pass to enter what Campbell (1949/1973) calls “the zone of magnified power” (Campbell, p. 69-89; Boyer, 2014a, pp. 23-27). From the shore, the pilgrims notice a boat that appears in the shadowy distance bearing an “Old Man/With white hair” who will take them in his boat to the “other side,/Where you’ll eat and drink of perpetual darkness” (Bang, 2012, p. 35). This old man is Charon, the boatman (p. 36), artistically depicted by Dore in the iconographic illustration above (see Fig. 2), one of the most beautiful and potent visual images of the night-sea journey motif ever portrayed in pictorial art.

Furthermore, Charon is only the first of many such archetypal threshold guardians or shadow presences (Campbell, 1949/1973, p. 245; Boyer, 2014a, pp. 31–35) encountered by the hero Dante in his journey into the depths. Threshold guardians are recurring figures in hero myths, as Campbell noted, important figures illustrating his hero quest paradigm, the leitmotif of the monomyth (Campbell, p. 30). This archetypal figure appears, in a wide variety of guises, throughout Dante’s Inferno. The motif of threshold guardian (or gatekeeper) is explicitly rendered in the passage in Inferno in which a “heaven-sent messenger” allows Dante and Virgil to enter the underworld City of Dis. “He came to the gate …,” Dante narrates. “He spoke from the horrible threshold” (Bang, 2012, p. 90). While most hero quests feature one, two, or perhaps a handful of threshold guardian figures, Dante’s Comedy—starting with Inferno—represents an exhaustive series of threshold passages, liminal passages between the worlds in which a parade of threshold guardians appear at various stages of the nekyia. This begins with the boatman Charon, followed by “Hideous Minos [who] stands snarling at the entrance” (p. 53), the “savage and bestial” Cerberus (p. 63), the three-headed dog that guards the entrance to Hades in Greek mythology, as well as the Minotaur (p. 111), the Harpies (p. 121), and a host of other threshold guardians the hero Dante encounters on his downward passage descending through the circles of the underworld.

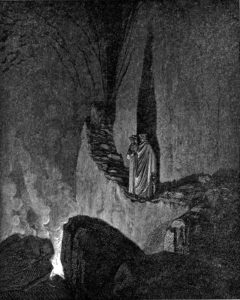

Fig. 3. The boatman Phlegyas ferries Dante and Virgil over the River Styx in the depths of the netherworld. Earlier in the narrative, they are ferried by another boatman, Charon. Illustration by Gustave Dore, published 1861.

The night-sea passage ends when Dante and Virgil complete their crossing over the murky water, landing on the far bank of the “pitch-dark plain” (Bang, 2012, p. 37). But in a rare example in mythic narrative, Dante describes a second night sea journey that further amplifies the crossing of the Acheron. After meeting Pluto—another threshold guardian or “entrance guard” (p. 68) to the fourth circle of Hell (in Roman myth, the god of the underworld himself)—the pilgrims come to a trench, the “deep-charcoal slope/Where the water becomes the marsh of the Styx” (p. 74). They circle the marsh where, at the beginning of Canto VIII, Virgil spies a second mythical boatman, Phlegyas, as he approaches “across the pond’s dirty water” (p. 79) in a small skiff. “As we took our seats and settle in/The worn prow took off, cutting a deeper wake” (p.80). This motif is again beautifully illustrated by Dore, whose imagery also explicitly illustrates that the nature of the nekyia journey is a descent into the Land of the Dead. In fact, almost the entire Inferno, spanning hundreds of pages, is an adventure set in the realm of departed spirits, Jung’s “land of ghosts,” the character Dante being the only mortal in the tale.

The pilgrims pass quickly in Charon’s boat over the “dead mill pond” (Bang, 2012, p.80) when a spirit surfaces from beneath the muddy water and demands that Dante identify himself. “Who are you?” demands the shade. This archetypal question of the hero’s identity recurs frequently throughout The Comedy (e.g., Inferno, see Bang, 2012, pp. 220, 238, and 258), a motif related to the archetypal figure of the hero-as-orphan. This question of identity offers an important clue to the nature of the quest as an archetypal origin myth of the hero (Boyer, 2011; 2012; 2014a). Early in The Inferno, this idea of the character Dante as archetypal or mythic orphan is subtly suggested when Virgil refers to Dante as his “foster-son” (Bang, 2012, p. 70), a characterization of the relationship between Virgil and Dante repeated throughout the narrative in their dialogue, referring to each other, respectively, as “father” and “son.” This symbolic figure of the archetypal orphan is a ubiquitous if not essential feature in stories of heroes who descend into the forested, watery, and subterranean depths of the other world.

To return to Dante’s narrative, Phlegyas, after circling the marsh in the skiff, sits the pilgrims down at the entrance to the underworld City of Dis, the city where the god of the underworld, Dis or Satan, dwells. Here Dante and Virgil encounter yet another threshold guardian personified as the Erinyes of Greek myth. Here at the threshold entering Satan’s City, “there rose up three-Hell-bent blood-streaked Furies” (Bang, 2012, p. 88).

Dante’s subterranean descent into the underworld of Hades-Hell. With the crossing of the Acheron, the protagonist-hero Dante initiates the lengthy pilgrimage into the depths of the underworld common to myriad mythic heroes before and since. This is the deep, dark topographical landscape of the underworld portrayed metaphorically as a subterranean route, a passage down into the depths of the world below the terrestrial surface of the earth. In Jung’s view, this is the well-known nekyia or katabasis journey so often described in Greek myths, where heroes from Theseus to Heracles—as Bang (2012, p. 92) acknowledged in her notes to Canto X—journey down into the shadowy depths of the cave-world imagined below Earth’s crust. In Homer’s Odyssey, the hero Odysseus journeys into watery depths to meet his dead parents—again, the imagery of dark depths as Jung’s “land of ghosts”—and the archetypal blind seer and prophet, Tiresias. In Dante’s Inferno, a Christian theological reinterpretation of The Aeneid, the character Dante journeys—having crossed the night-seas of Acheron and Styx—with the shade of the dead poet Virgil into the subterranean underworld realm of Death, occupied by legions of spirits and shades encountered along the way.

Fig. 4. Virgil and Dante descend into the depths of the mythic underworld of Hades (or “Hell,” in the Christian conception inspired by Dante). Illustration by Gustave Dore, published 1861.

“I found myself on the brink/Of a deep and melancholy chasm/…so dark and deep and impenetrable that/I couldn’t identify anything” (Bang, 2012, p. 41). Gazing down into this ink-dark, unfathomable abyss, Virgil summoned his protégé and companion to follow him. “That’s how we’ll descend into the unlit world below” (p. 41). Practically from beginning to end, Dante’s journey in The Inferno is explicitly downward, a journey of descent—to borrow Campbell’s term, downgoing—through nine descending circles of Hell. Dante was apparently deliberate[5] in his crafted imitations of the directional, topographical landscape through which he (as character) made his way. In the above passage, the author specifically described his character’s trajectory as a journey of descent; he and Virgil are about to “descend” into the “unlit world below.” And throughout their journey into the depths of the dark abyss, Dante the author refers to the adventure using similar terms. For one example, in Canto VII, when Virgil—after comforting Dante that the threshold guardian, Pluto, cannot prevent their journey “down this rock”—turns to Pluto and upbraids him: “There is a reason we’re making this descent [italics mine]. Upstairs wants him to go down” (p. 71).

Returning to the narrative, the pilgrims—Dante and Virgil—enter the “first circle of the black abyss,” (Bang, 2012, p. 41) the region of limbo that lies, according to Dante the author, between Acheron and the proper entrance to Hell as underworld (p. 47). Such imagery of descent into a deep, dark abyss spans the succeeding 30 Cantos of The Inferno. “Below this rock there are three more circles,/Each one lower than the next” (p. 103). Referring to the monster Geryon, another gatekeeper, Dante says: “From now on, we’ll always go down via escalators/Like these” (p. 161). He continues: “[Geryon] swims on, slowly, slowly, wheeling down/In continuous descent” (p. 162).

In the apocryphal tradition of Christianity, this subterranean route into the depths is suggested in the event, immediately following Jesus’ crucifixion and death, where Jesus Christ—like Heracles in Greek mythology, Inanna in the Descent of Inanna (Wolkstein & Kramer, 1983), and countless other heroes and gods in world mythology—descended into the subterranean underworld-netherworld realm ruled by Satan, the pagan Hades-Pluto, lord of the underworld in Greco-Roman mythology. In Christian tradition, in which the hellish imagery of Inferno is historically influential, the underworld of Hell is ruled by Satan. It is into this underworld realm of the dead that Jesus descends for the mythic three days and nights preceding the miracle of his apotheosis, resurrection,[6] and ascension to Heaven. In Christian narrative this story is referred to as Christ’s “Harrowing of Hell,” the nearest analogue in Christian mythopoeic literature of the transformative hero journey of subterranean descent-ascent as a form of initiatory death-rebirth. When Jesus miraculously ascends from the underworld depths of Hell, the realm of the dead—Jung’s “land of ghosts”—he is no longer Jesus, the man, but Christ, the resurrected semi-deity (Boyer, 2014c; Boyer, 2017b), a narrative trajectory closely imitated more than a millennia later by the mythic poet and literary hero, Dante.

Dante’s wedding of the myth-motifs of the hero quest in the depths of forests with Jung’s night sea journey and the analogous myth-motif of subterranean descent into Hades—“the land of ghosts … beyond this world”—is a rare example in literary mythology that forcefully illustrates the nearly identical motifs of Campbell’s heroic wilderness landscape and Jung’s thesis of symbolic identity between the myth-motifs of descent into the depths of a dark watery abyss and the descent into the subterranean underworld (i.e., Hades or Hell).

Concluding Discussion

In the realm of world mythology and mythopoeic literature, Dante’s Inferno occupies a special position in its unique artistic and literary portrayal of the mythic hero’s journey of descent. With the exception of J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic literary trilogy, Lord of the Rings, perhaps no hero journey’s mythopoeic landscape compares in scope to Dante’s nekyia, imagined as an epic mythic journey of descent into Jung’s collective unconscious that utilizes three major archetypal routes into the underworld depths—by forest, night-sea, and subterranean descent—and whose entire adventure takes place in the setting of an underworld described in breathtaking scope and exhaustive detail.

However, the mythic hero quest journey remains incomplete if only the journey of descent or death is described, an important limitation in a study of brief scope as presented in these pages. As the transformative journey of Jesus Christ in the Harrowing of Hell suggests, the descent into the underworld is merely a prelude to the story’s important conclusion. The journey of descent sets the stage for the subsequent journey of ascent and return to the upper world, the semi-divine hero now transformed, regenerated, and resurrected (i.e., reborn) from death. In Virgil’s Aeneid (n.d./2006), the Sibyl of Cumae warns the hero Aeneas that the “descent to the Underworld is easy./Night and day the gates of shadowy Death stand open wide,/But to retrace your steps, to climb back up to the upper air—/There the struggle, there the labor lies” (p. 186).

Indeed it is this difficult journey of return (Campbell, 1949/1973, pp. 193-244) to the upper light—the inverse of the descent in which the triumphant hero returns through a journey of ascent to the light of the ordinary but newly transformed world—that makes the essential symbolic point of the tale. The point is not the hero’s death, but the transformation symbolized as the hero’s death (in its myriad forms) followed by renewed or regenerated life (i.e., Jung’s individuation process). The journey of Dante’s descent explored in this study is only the first part of this narrative trajectory or story arc—the tale of the hero’s death or symbolic encounter with Death in the realm of the dead. The return trip, Dante’s journey of ascent or return, begins at the conclusion of Inferno, when the pilgrims, after encountering Satan himself, enter “that secluded passage/That would lead us back to the lit world” (Bang, 2013, 330). Their initial journey of ascent is extremely efficient, as Dante and Virgil climb out through a round opening to “once again catch sight of the stars” (p. 330). But this return merely marks the beginning of Dante’s epic journey of ascent, a journey described in unparalleled detail and scope in The Purgatorio and Paradiso that complete his remarkable tale.

In the ancient myth of the goddess Inanna, one of the earliest deities whose nekyia or mythic journey of descent, based on oral storytelling tradition, was recorded in textual form, the complete cycle of Campbell’s (1949/1973) “downgoing and upcoming” is described when the goddess’s father, the great god Enki, teaches Inanna about the cyclical form her journey must take. Her journey is concisely described in the myth: “Descent into the underworld! Ascent from the underworld!” (Wolkstein & Kramer, p. 15). This journey, like the path trodden by Virgil’s hero Aeneas, and by Dante more than two millennia later, is a journey of transformation—suffering, death, and transfiguration—as psychologically relevant today as when the primordial myths of indigenous societies throughout the world were originally told. This archetypal journey of descent and ascent—as Jung, Campbell, Mircea Eliade (1958) and scores of Jungian scholars indicate (Boyer, 2011; 2014b; 2017a; 2017b)—can be interpreted as a literary expression of the presumably universal initiatory ordeal of symbolic death and rebirth told in countless local variations in the metaphorical language of psyche—a mythopoeic grammar of psychological individuation and authentic human identity and wholeness expressed in ever-recurring metaphors and symbols from which mythopoeic narratives like Dante’s Inferno, and indeed the entire Divine Comedy, are constructed.

Conclusion

This paper represents the continuation of the early amplification and interpretation of archetypal material in Dante’s mythopoeic literary masterpiece, exemplified by Jungian scholar Helen Luke’s (1989) wonderful interpretation in From Dark Wood to White Rose (1989). This interpretive excavation of Dante’s Comedy from the perspective of Jungian psychological criticism, suggested by Jung himself in his early career comments on Dante,[7] has only recently begun. More comprehensive interpretations of Dante’s archetypal imagery along these lines seem worthy of more than one graduate thesis or doctoral dissertation.

References

Alighieri, D. (n.d./1970). The divine comedy: The inferno, the purgatorio, and the paradiso (J. Ciardi, Trans.). New York, NY: New American Library.

Alighieri, D. (n.d./2012). Dante Alighieri: Inferno (M.J. Bang, Trans.). Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press.

Baum, L.F. (1900). The wonderful wizard of Oz (1st ed.). New York, NY: George M. Hill.

Bedier, J. (1945). The romance of Tristan and Iseult (H. Belloc, Trans.). New York, NY: Pantheon.

Boyer, R.L. (2011). Key archetypes in the Celtic myth of Tristan and Isolde: A brief introduction. Retrieved at https://www.academia.edu/622341/Key_Archetypes_in_the_Celtic_Myth_of_Tristan_and_Isolde_A_Brief_Introduction

Boyer, R.L. (2012, August). Introduction to the mythic orphan: Archetypal origins of the hero in myth, literature and film. Paper presented at the Symposium for the Study of Myth, Santa Barbara, CA.

Boyer, R.L. (2014a). The other world of Oz: The threshold passage of Dorothy Gale. In Coreopsis: Journal of Myth & Theater, 3(2), Spring/Summer 2014. Retrieved at https://www.academia.edu/7574495/Entering_the_Other_World_of_Oz_The_Threshold_Passage_of_Dorothy_Gale

Boyer, R.L. (2014b, June). To die, and be reborn: The death-rebirth motif in myth & rite, literature & film. Paper presented at the International Conference of the International Association for Jungian Studies (IAJS), Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ.

Boyer, R.L. (2014c, November). The Gospel as transformative myth: Individuation imagery in DeMille’s King of Kings. Unpublished manuscript, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA.

Boyer, R.L. (2017a). The rebirth archetype in fairy tales: A study of Fitcher’s Bird andLittle Red Cap. Coreopsis: Journal of Myth and Theatre, 6(1), Spring 2017). Retrieved at http://www.societyforritualarts.com/coreopsis/spring-2017-issue/the-rebirth-archetype-in-fairy-tales/

Boyer, R.L. (2017b). The sign of Jonah: Initiatory symbolism in Biblical mythopoetics. Coreopsis: Journal of Myth and Theatre, 6(2), Autumn 2017. Retrieved at http://www.societyforritualarts.com/coreopsis/autumn-2017-issue/portfolio-item/the-sign-of-jonah-initiatory-symbolism-in-biblical-mythopoetics/

Campbell, J. (1973). The hero with a thousand faces (3rd ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University. (Original published 1949)

Eliade, M. (1958). Rites and symbols of initiation: The mysteries of birth and rebirth (W.R. Trask, Trans.). New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Ford, P. (Trans. & Ed.). (1977). The Mabinogi and other medieval Welsh tales. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California.

Frye, N. (1963). Fables of identity: Studies in poetic mythology. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace World.

Gennep, A. van (1975). The rites of passage. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

Hillman, J. (1979). The dream and the underworld. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Homer (n.d./1967). The Odyssey of Homer (R. Lattimore, Trans.). New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Jung, C. G. (1958). Psychology and religion (R.F.C. Hull, Trans.). In H. Read et al (Series Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (vol. 11, para. 88; 1st ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.

Jung, C. G. (1992). The psychology of the transference (R.F.C. Hull, Trans.). In H. Read et al (Series Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (vol. 16). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University. (Original published in German 1946)

Jung, C. G. (2012). Introduction to Jungian psychology: Notes of the seminar on analytical psychology (S. Shamdasani, Ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University. (Original published 1925)

Luke, H. (1989). Dark wood to white rose: Journey and transformation in Dante’s Divine Comedy. New York, NY: Parabola.

Mason, H. (n.d./1972). Gilgamesh: A verse narrative. New York, NY: New American Library.

Maupassant, G. du (1989). The horla. In The dark side: Tales of terror and the supernatural (A. Kellett, Trans.). New York, NY: Carroll & Graf.

Milton, J. (1982). Paradise lost & paradise regained (C. Ricks, Trans.). New York, NY: New American Library.

Neumann, E. (1974). Art and the creative unconscious: Four essays (R. Mannheim, Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.

Rank, O. (1964). The myth of the birth of the hero and other writings (P. Freund, Ed.). New York, NY: Alfred Knopf.

Virgil (n.d./2006). The Aeneid (R. Fagles, Transl.). New York, NY: Penquin.

Wolkstein, D. & Kramer, S.N. (Trans.). (n.d./1983). Inanna: Queen of heaven and earth: Her stories and hymns from Sumer. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

List of Illustrations

Fig. 1. Dante initiates his journey by entering the symbolic depths of a dark, “dusky” wood. Illustration by Gustave Dore, published 1861.

Fig. 2. Upon entrance to the underworld, Dante and Virgil begin a night-sea journey when the boatman of the underworld, Charon, approaches to take them to the Other Shore. Illustration by Gustave Dore, published 1861.

Fig. 3. The boatman Phlegyas ferries Dante and Virgil over the River Styx in the depths of the netherworld. Earlier in the narrative, they are ferried by another boatman, Charon. Illustration by Gustave Dore, published 1861.

Fig. 4. Virgil and Dante descend into the depths of the mythic underworld of Hades (“Hell,” in the Christian conception inspired by Dante). Illustration by Gustave Dore, published 1861.

Endnotes

[1] See the author’s Entering the Other World of Oz: The Threshold Passage of Dorothy Gale (Boyer, 2014a, pp. 3-6) for a discussion of mythopoeic literature including a definition of the term.

[2] An extensive discussion of Jung’s theory of the archetypes and its relation to Campbell’s monomyth can also be found in the author’s published paper Entering The Other World of Oz (Boyer, 2014a, pp. 6–17). For readers unfamiliar with Jungian theory and Campbell’s monomyth paradigm, this section of the Oz paper provides a summary introduction to the theoretical and interpretive approach taken in the current study.

[3] For the sake of consistency, all citations from The Inferno are from the Mary Jo Bang translation (2012).

[4] Campbell discussed this figure at length in his chapter on “Supernatural Aid” (pp. 69–77) in The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949/1973). The author also discussed this figure in “Meeting the Mentor & Securing Supernatural Aid” in Entering the Other World of Oz (Boyer, 2014a).

[5] According to Jung, archetypal images can appear spontaneously and unconsciously in the artistic creative process.

[6] Jung includes resurrection as a form of his rebirth archetype, the “archetype of transformation.” See Boyer, The Rebirth Archetype in Fairy Tales, 2017a.

[7] In Lecture 12 of a seminar by Jung discussing his theories of analytical psychology, given June 8, 1925 (C. G. Jung, 1925/2012, p. 105), Jung asserted that “Dante got his ideas from the same archetypes” as the Gnostics and as imagined in Jung’s own fantasies of “Elijah.”

Ronald L. Boyer is a scholar, teacher, and award-winning poet, fiction author, and screenwriter. He holds an MA in Depth Psychology from Sonoma State University and is a graduate of the Professional Program in Screenwriting at UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television.

Ronald L. Boyer is a scholar, teacher, and award-winning poet, fiction author, and screenwriter. He holds an MA in Depth Psychology from Sonoma State University and is a graduate of the Professional Program in Screenwriting at UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television.

Ron is currently a doctoral student in Art and Religion at the Graduate Theological Union and UC Berkeley. His scholarly research emphasizes Jungian archetypal theory applied to mythology, literature, and film, with a concentration on mythopoeic imagery in the art of Dante Alighieri, William Blake, and J.R.R. Tolkien. He is an associate editor/reviewer for the peer-reviewed journal, the Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology, and a referee and regular contributor to the peer-reviewed journal, Coreopsis: Journal of Myth and Theater. Ron has presented academic papers at the first Symposium for the Study of Myth at Pacifica Graduate Institution, the International Conference for the International Association for Jungian Studies at Arizona State University, and other forums.

Ron is a two-time Jefferson Scholar to the Santa Barbara Writers Conference and two-time award-winner for fiction from the John E. Profant Foundation for the Arts, including the prestigious McGwire Family Award for Literature. His poetry has been featured in the scholarly e-zine of the Jungian depth psychology community, Depth Insights: Seeing the World with Soul, Mythic Passages: A Magazine of the Imagination, Mythic Circle, the literary magazine of the Mythopoeic Society, and many other publications.

His writings can be accessed at his scholarly website, www.gtu.academia.edu/RonaldLBoyer/papers